'We have suffered because we were Negroes': It took this man 200 days to become a legend in the fight against Western exploitation

Exactly 200 days passed between June 30, 1960, when Patrice Lumumba made his iconic independence speech, and January 17, 1961, when he said his last words. During that time, Lumumba became one of the most famous people on Earth: a hero for Africa but a villain for the West. He was a dazzling star – exactly the kind they wanted to snuff out.

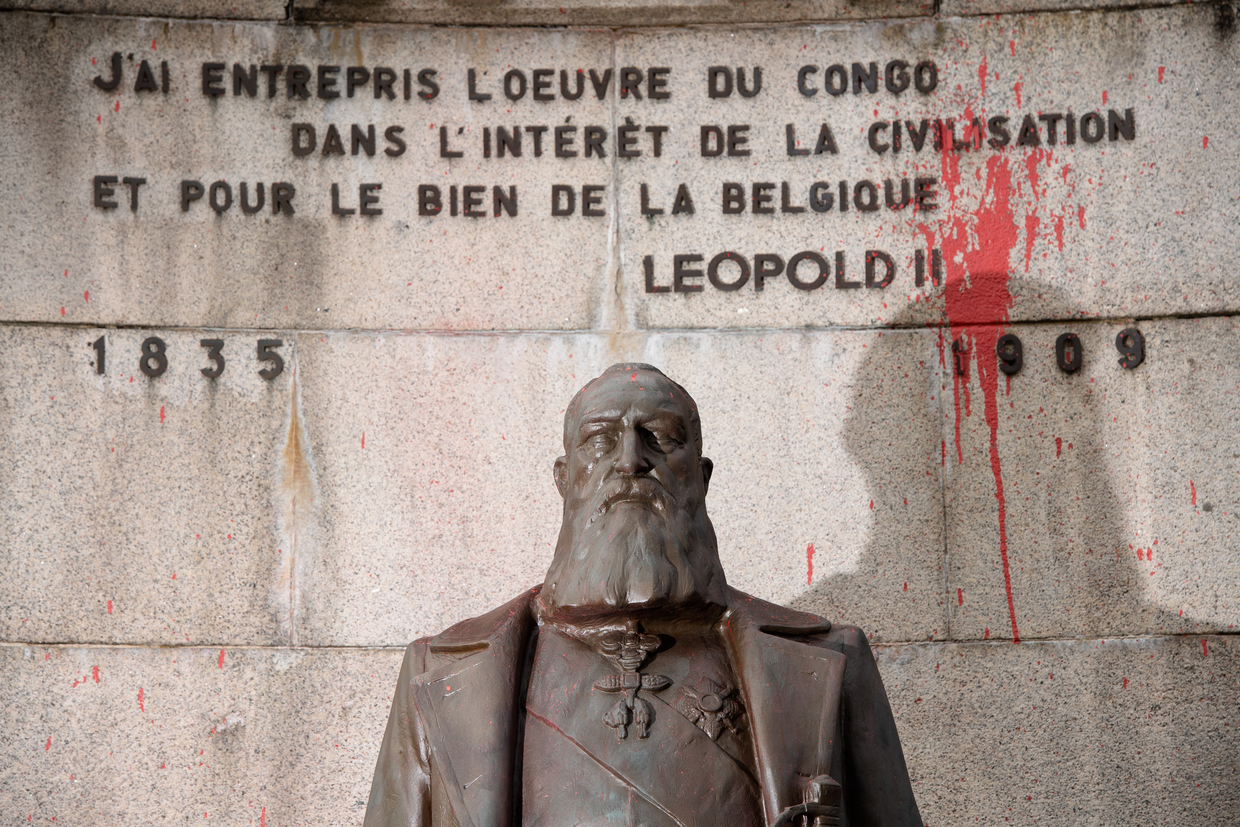

Congo under Belgium

In 1900, 90% of the African continent was under European control. Of all that land, 11% belonged to King Leopold II of Belgium. The Congo Free State was his personal domain – and a profitable one.

The invention of the pneumatic tire swelled world’s demand for natural rubber, of which the Congo Free State was one of the primary sources. To meet the demand, King Leopold’s colonial officials set quotas for how many kilos of rubber natives had to pay as tax. Failure to achieve the norm resulted in harsh repressions: the Force Publique, the king’s private army, would arrive, set huts aflame, and shoot people at random. As proof that their bullets had been rightly spent, troops chopped off their victims’ right hands and piled them in baskets.

This happened everywhere, from Bukavu to Boma – on a daily, weekly, and monthly basis. Torture, murder, beatings, rape, starvation – the Congo Free State became hell on Earth. While it is true that in all colonies Europeans ruled with an iron fist, at least they attempted to offer a veneer of legality. In King Leopold’s Congo, there was no law.

Soon the news about the atrocities in the center of Africa became known to the civilized world. Evidence of the inhumanity triggered international outrage, culminating in a campaign to end Leopold’s genocidal reign. In 1908, the king reluctantly sold the African state to the Belgian government – and thus the land became the Belgian Congo. The situation partially improved – the wanton killing of natives was declined and rubber quotas were abolished. World War I and the 1920s economic boom led to the colony’s prosperity. In 1925, a man was born there whose name will forever be inscribed in the history of his state, the continent, and the world.

Lumumba’s early years

Patrice Lumumba’s childhood and youth were not much different from his peers – with one exception: he was always keen to learn. He considered a good education as key to a successful career. At the age of 20, Lumumba got a job as a clerk at a government office. To improve his French, he took night classes and became an avid reader of everything he could get his hands on, from Larousse Dictionary to old newspapers. Lumumba was keen to join the Congo’s growing black middle class. In 1947, he attended a nine-month training program at the government’s postal school in Leopoldville, the colony’s capital. He graduated top of his class, which secured him a job as a clerk in the Stanleyville post office. Eventually he became an “évolué” (French for “evolved person”).

The term was reserved for natives who, in their eagerness to emulate European settlers, became poster boys of colonialism. In theory, this designation granted évolués the same legal status as Europeans – though in practice they were still second-class and mostly illiterate. The Belgians had long opposed higher education for Congolese, emphasizing vocational training instead. The natives could become carpenters but not architects, medical aides but not doctors, lab assistants but not scientists, clerks but not lawyers. For the same reason, Belgium had kept the Congolese politically illiterate, clinging to the principle of “pas d'élites, pas de problèmes” (no elites, no problems).

Surprisingly, this situation suited the majority of évolués. Even in the mid-1950s, there was no talk among them of independence. Lumumba was also a proponent of gradual colonial development, and lavished the Belgians with praise. Any flaws in the colonial system, he argued, were mere failures of execution. This stance won him the confidence of colonial officials.

In 1954, Lumumba was granted an audience with Belgium’s minister for the colonies and in 1955 with King Baudouin during his visit to the Congo. The following year, he was chosen along with a group of évolués on a government-sponsored tour of Belgium. Everything seemed to be going smoothly – until in July 1956, he was arrested on charges of embezzlement. He was sentenced to two years but received a pardon from king after 14 months. He then moved to Leopoldville and began to take an active part in politics. In October 1958, Lumumba was among the group of évolués that organized the “Congolese National Movement” political party (Mouvement National Congolais – MNC). Its position was a reformist one and called for “independence within a reasonable time.”

Unexpected speech

It was the All-African Peoples’ Conference in Accra in December 1958 that marked a turning point in Lumumba’s thinking. There he met politicians, diplomats, labor unionists, intellectuals, leaders, and revolutionaries from fellow African countries. The event gave him his first real exposure to pan-Africanism, the idea that people from across the continent were engaged in the same collective struggle. Lumumba also came to believe that Congolese politics had nothing to do with the real fight for independence. He gave up hope of a “cooperative solution to the Congo’s future.” From then on, his motto became: “Down with colonialism! Down with the Belgo-Congolese community! Long live immediate independence!”

Throughout 1959, Lumumba traveled all over the Congo, holding rallies in towns and villages, spreading words of independence and encouraging people to join the MNC. Soon his inexhaustible devotion started to bear fruit – people began to believe that the country could truly become independent. At the end of 1959, he was arrested again, this time on charges of causing civil unrest. While he was in jail, Belgian authorities agreed to demands from Congolese activists and set up a roundtable to discuss the terms of independence. Lumumba’s imprisonment added to his popularity. When the Roundtable Conference started in January 1960 in Brussels, Congolese delegates announced an ultimatum: Lumumba had to be released so he could attend the event. The Belgians relented.

The date of the declaration of independence was set as June 30, 1960, and before that general elections were held in May – which the MNC won. Lumumba took the post of prime minister, while Joseph Kasavubu became president of the Congo.

Lumumba was not due to speak on that momentous day – only King Baudouin and President Kasavubu were expected to give speeches. The king’s speech was full of colonial paternalism and cohesion wishes. Kasavubu spoke next, echoing the king’s call for unity. Then, to everyone’s surprise, Lumumba took to the podium.

“Men and women of the Congo – I salute you... Our wounds are still too fresh and painful to erase from our memories. We have known backbreaking work, demanded in exchange for wages that allowed us neither to feed, nor dress, nor house ourselves decently, nor to raise our children as loved ones. We have suffered contempt, insults, and blows morning, noon, and evening, because we were Negroes. We have known that our lands were seized in the name of supposedly legal texts that recognized only the rights of the strongest. We have known that the law was never the same for whites and Blacks: accommodating for one, cruel and inhumane for the other. But we say to you out loud: from now on, all that is over!”

The audience was in awe: the Africans were enraptured, the Europeans alarmed. Lumumba went on, declaring that the Congo’s independence marked “a decisive step towards the liberation of the entire African continent!” The applause turned into the loudest ovation the Congo had ever heard. The speech was immediately reprinted by the world’s media. While in Asia and Africa it was greeted with enthusiasm, Europe and America saw it as a clear and present danger. From that moment on, Lumumba was a marked man. Belgium, as the former master of the Congo, and the US, as the main warmonger of the Cold War, were ready to deal with the moderate Kasavubu, who would not encroach on the main issue: the economy. In contrast, the radical Lumumba had to be removed. In terms of strategically important minerals, the Congo was abundant with copper, tin, cobalt, zinc, cadmium, germanium, manganese, silver, and gold. It also had what the US needed most – radium and uranium. These treasures had to be safeguarded from “dangerous people like Lumumba.”

Unrest in the country

On July 5, 1960, the Congolese army mutinied; they wanted promotion in rank and pay, but were told that “before independence = after independence.” Rioting followed; first came attacks on white officers, then on all whites. In a matter of days, mutiny and violence spread across the country. White Congolese fled. To protect them, Belgian troops landed in the mineral-rich Katanga province, where they were welcomed by local leader Moise Tshombe, a longstanding antagonist of Lumumba. Very soon, Tshombe declared Katanga an independent state. The real reason behind the secession was the discreet backing of the Belgian mining giant Union Minière, which promised full support in exchange for mineral rights – and even more discreet backing from the American CIA.

The prime minister thus has an army mutiny, a struggling economy, the flight of skilled workers, civil unrest, and a breakaway province on his hands – and had to deal with it simultaneously. He appealed to the UN for assistance, with a request for troops to be sent to support the government and keep the peace. UN leader Dag Hammarskjold agreed on condition that the troops would not be used by Lumumba to pacify Katanga. Still, the deployment of “Blue helmets” led to the UN being accused of interfering in the Congo’s internal affairs. Seeing as the UN wasn’t much help, Lumumba went to the US but was dismissed by the Eisenhower administration, not least because he was marked as a “red” by the CIA and received neither the high-level reception nor the military assistance he sought. The third option was to appeal to the USSR for military aid, which he received. Soviet assistance was limited, but the US and Belgium were greatly alarmed by the mere fact.

By mid-August 1960, politicians in the Congo and in the West came to the conclusion that Lumumba was a “fractious and insecure oddball” – so the plan to oust him began to form. It seems that everyone wanted to remove him from power, while even the UN had no objections.

Dismissal and execution

On September 5, President Kasavubu announced the dismissal of Lumumba as prime minister. In response, Lumumba announced the removal of Kasavubu. Parliament refused to recognize these decisions and called for a peaceful resolution. The president and prime minister were deadlocked. The Congolese army chief of staff, Colonel Joseph-Désiré Mobutu, eventually launched a coup, dismissing both Kasavubu and Lumumba and establishing a new provisional government. Later it was discovered that Mobutu (financially backed by the CIA) had sided with Kasavubu against Lumumba. The ex-PM was placed under house arrest under UN guard.

On November 27, Lumumba escaped. As soon as the news broke, a huge search operation was launched with helicopters and mobile units. Significant help came from CIA Congo Chief of station Larry Devlin, who provided full-scale maps and helped Mobutu to identify the key points of Lumumba’s suspected escape route, including ferry crossings. On December 1, Lumumba was arrested by an army patrol while crossing the Sankuru River at Lodi. Witnesses were Ghanaian UN soldiers and British officers, to whom Lumumba appealed. What he didn’t know was that the head of the UN operation in the Congo, Rajeshwar Dayal, had issued strict order to “Blue Helmets” across the country: the UN would not be accused again of interfering in the Congo’s internal affairs, so it would assist neither Lumumba nor his pursuers. Thus, UN soldiers looked on with indifference as Lumumba’s captors beat and rifle-butted him. He was then taken to a nearby airport and brought to the capital.

For weeks, Lumumba and his associates Maurice Mpolo and Joseph Okito were hauled from prison to prison. On January 17, they were brought to Katanga’s capital, Elisabethville. The very same day, the Katangese cabinet led by Tshombe gathered for a meeting and concluded that Lumumba must be dealt with at once. The task fell to the Belgians in Katanga’s service: Police Commissioner Frans Verscheure and Officer Julien Gat. About 20:30 the same day, Lumumba, Mpolo, and Okito were forced into a car and driven in the direction of Jadotville, followed by other vehicles with Katangese ministers and soldiers. The cavalcade stopped at a designated spot near the village of Mwadingusha, where graves had already been dug. Verscheure and Gat assembled the soldiers. Tshombe and his ministers stood nearby. Each prisoner was individually placed in front of their grave. Gat gave the order to the firing squad – Lumumba’s turn came last. His final words were: “To you I have nothing to say.” The soldiers threw dirt over the bodies and everyone hurried away. In his diary, Verscheure wrote: “9.43 L. dood” (Lumumba dead). His 200 days in the independent Congo were over.

The Katangese government wanted to keep it a secret, but by the next morning the burials had been discovered and rumors began to swirl. Katangese Interior Minister Munongo ordered Belgian policeman Gerard Soete to exhume the dead and dispose of the bodies. The remains were dug up, dismembered, and dissolved in acid. Gerard Soete plucked a tooth from Lumumba as a souvenir. (Soete confessed this at the very end of the last century. After Soete’s death, Lumumba’s tooth was confiscated by the Belgian government and delivered back to Africa).

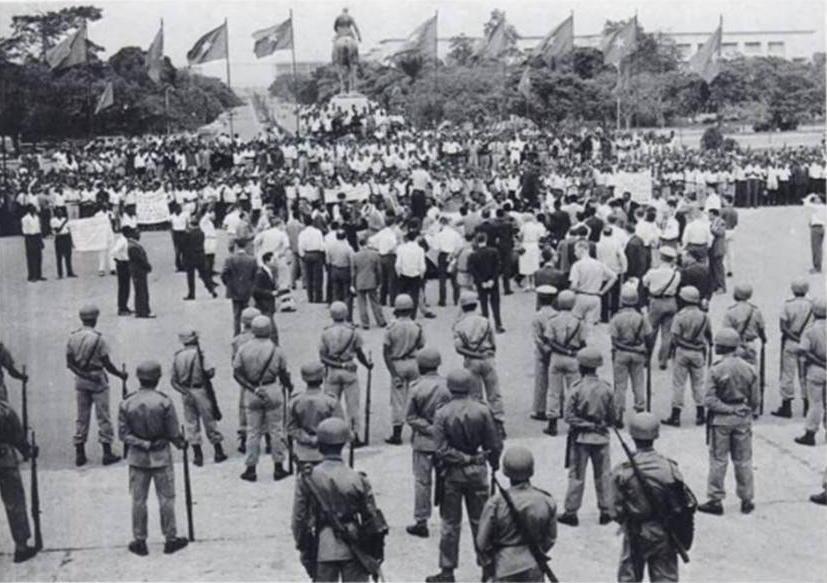

Lumumba’s death was only announced on February 13, amid a disinformation campaign that he had escaped from prison. In many countries, the news triggered demonstrations and protests. In the Congo itself, Lumumba was recognized as a hero years after his murder.

Who was responsible for the killing of the first prime minister of Congo? Many people wanted his death, starting from US President Dwight D. Eisenhower and King Baudouin, to CIA chief Allen Dulles and Joseph Mobutu. From the very start, Belgium tried to undermine the Lumumba government and the US quickly followed. The UN ignored the probability of an assassination and did nothing to protect the prime minister. Belgians with subtle American help goaded the Congolese to imprison Lumumba. With Western encouragement, Kasavubu and Mobutu sent him to Katanga – the only place in the Congo where he was 100% doomed.

In 1960, 16 African states gained independence. The largest and most potentially richest of these was the Congo. But the West did not want to part with its wealth. Instead of direct colonial rule, a scheme of indirect control was devised – the new leaders of the Congo were only required to respect the new order. Lumumba stood in the way of this neo-colonial plan: the population would benefit from total decolonization, but not big business. Therefore, he had to be stopped.