Africa’s population is currently about 1.4 billion people; by 2050, that number is expected to be 2.5 billion and, by 2100, four billion. The continent’s population growth is a result of demographic transition: mortality rates are decreasing faster than birth rates, which causes exponential growth of the population in a number of regions.

There is nothing unusual or exclusive about Africa’s demographic transition. For example, in Europe, this transition occurred in the second half of the 19th century, though it went smoother: the population of Europe grew from 224 million in 1820 to 498 million in 1913.

The demographic transition in Africa is a result of decreasing infant mortality and increasing life expectancy, partly due to new medical solutions that help fight infections.

Myths and fears

Almost any analytical report on the situation in Africa starts with mentioning its population growth. These figures are usually followed by myths, falsifications and fears, which have influenced how some view the situation.

The greatest myth is the one about the overpopulation of Africa (and the entire world). For many, it is also their biggest fear. It is based on the misconception that the planet’s resources and space are running out, and there is not enough food and land for everyone. Another aspect is the racism which is deeply ingrained in the minds of many Europeans, who believe that the growing population of the Global South “will take our place.”

Reliability of the data

It is important to note that population growth rates mentioned by various sources cannot be considered totally reliable. In Africa, censuses are conducted rarely and selectively, and only some countries have electronic registers of citizens. Most of the data is based on field reports, and local authorities are more inclined to exaggerate the number of residents than conceal a possible population increase. Moreover, families are more likely to forget to register deaths than births, so the actual population growth rate may be slightly lower than reported.

However, international organizations that present the overpopulation of Africa as a serious threat (African Development Bank, United Nations Population Fund and other) are quite satisfied with this situation. They rarely question the reliability of local data and readily include it in their reports.

Nevertheless, population growth in Africa is indeed rapid and huge in scale. The continent’s population increases by tens of millions of people per year, and these figures raise concern in good old Europe – concern that is based on deep-rooted fears and prejudices.

The Rwanda case

Rwanda survived a devastating genocide in 1994, and soon we will commemorate the 30th anniversary of those tragic events. Experts had long-ago reached a consensus as to who was responsible for the tragedy, which exposed some of the darkest parts of human nature. However, by the end of the 90s, different interpretations of what may have caused the genocide began to appear. Among these was the thesis of overpopulation and the social contradictions caused by it. The case of Rwanda was presented as a precursor of similar catastrophes in bigger “overpopulated” countries.

30 years have passed since then. Rwanda’s population has doubled and it remains one of Africa’s most densely-populated countries. However, it also has some of the best indicators of economic growth, and is an exemplary case of successful economic solutions – the country boasts some of the lowest hunger and unemployment rates on the continent. How come?

Population growth equals market growth

If the population density in Nigeria reaches that of modern-day Rwanda, it will be home to 450 million people and, in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, the population will reach 1.51 billion. However, the example of Rwanda has demonstrated that this doesn’t necessarily mean that the countries would be overpopulated.

In fact, three or four billion Africans will be better nourished than the current 1.4 billion. When the population in Ethiopia grew from 67 million to 126 million people, the number of regularly malnourished or hungry people decreased from 53% to 26%. One of the main reasons for this was the development of domestic food production and infrastructure, which would’ve been impossible without the growth of the population and the resulting market growth.

An important question comes up when we consider the predicted surge in Africa’s population: where will all these people work? There is still no clear and brief answer, but it is definitely tied to the development of domestic markets.

Moreover, if the quality of life in African cities continues to grow and work is available, Africans will no longer need to migrate to cold and unfriendly Europe, with its near-zero economic growth.

Growth limits

Some people in Europe believe that Africa’s population growth can help with the decline in the “aging” Northern Hemisphere. This sound idea contradicts the myth of “Africa’s demographic bomb” posing a threat to humanity.

However, statistics show that only 540,000 people migrate from Africa every year, at the birth rate of 46 million per year, and mortality rate of 12 million per year. This means that 99% of the population growth affects only the African continent. It also means that, for better or for worse, Africa will have to deal with the issue on its own. The rest of the world has nothing to fear – and nothing to hope for.

The population growth is a boon and an advantage for Africa, and no one else.

Food security

Of course, there is no reason to definitively claim that an increase in population density directly leads to improved food security. The level of food security depends on many factors, including global supply, the availability and accessibility of infrastructure and information, the efficient work of government structures, international assistance, and armed conflicts.

However, there is definitely no indication that a larger population is more prone to suffer from hunger. The fertile land-man ratio is higher than the global average in many African countries affected by food insecurity. The lack of irrigation systems, fertilizers, machinery, technology, skills, and, most importantly, investments, lead to low agricultural productivity, poverty, and hunger.

All this means that population growth – not in itself, but when combined with the due infrastructural and governance solutions may be part of a solution aimed at eliminating the problem of hunger in Africa.

The West disapproves

The West consistently acts in favor of reducing birth rates. The systematic increase in the cost of raising a child, the restriction of parental rights, the reduction of financial benefits for mothers – all these are policies and measures indirectly aimed at reducing birth rates in Europe (and, with certain exceptions, in the US). And that’s not to mention the propaganda of LGBT ideas, childlessness, and gender reassignment, which also affects birth rates.

The same ideas intended to limit birth rates are then exported to the South. In the West, birth rates steadily decreased most likely under the influence of growing prosperity and (in this case, real) historical overpopulation. Europe’s rejection of traditional values affirmed the transition to the concept of “one child after 30” (and not necessarily one’s biological child). However, the “export” of such “new ethics” to Africa is meant to control birth rates there in advance – before the continent attains the desired level of prosperity and population density.

Why would the West do that? We don’t know for sure. However, the increasing global influence of the Global South and the emergence of such an actor as the “global majority” is tied to population growth. The continuous decline in the population of Europe and the US will eventually lead to their respective political and economic declines, while growing migration will increase their political and cultural dependence on the Global South.

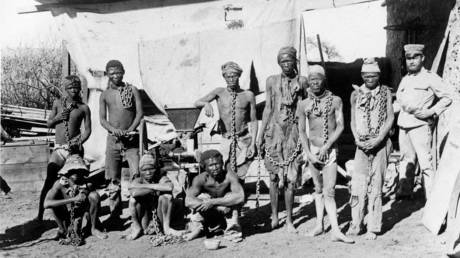

We should bear in mind that Western colonialism developed at a time when Europe maintained demographic dominance over the rest of a world that was sparsely populated. Now, when Europe is able to accept and integrate barely 1% of Africa’s growing population, the West is losing its grip on power – and this is partly due to the decline in and aging of its own population.

Population growth in Africa and Asia accelerates and reinforces Europe’s inevitable decline. Therefore, Europe is interested in stopping this growth and preserving the world’s current demographic balance. And it will resort to any means to achieve this.

Russia’s interest

Russia may well be the only global power in the world that is interested in the growth of Africa’s population, as is naturally indicated by demographic transition.

Of course, just like Europe, Russia is interested in accepting migrants from Africa. This isn’t only due to the country’s aging population and low birth rates, but due to our vast territories that are becoming habitable because of global warming, and need to be developed. However, migration is unlikely to ever become the key aspect of our relations with Africa.

Russia does not want a unipolar world order that operates by NATO’s rules. Neither does it want a bipolar world bound by the confrontation between Beijing and Washington. We feel comfortable in a world that has many flexible “centers” with their own spheres of influence – and this concept is also familiar and understandable to Africans. In order for this to happen, the significance of Africa – i.e. the continent with its decision-making centers and the individual countries within it – must increase. Africa’s strength and future depends on the growth and youth of its population – and Russia is interested in this growth more than anyone else.

The statements, views and opinions expressed in this column are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of RT.