The triumph of Adwa: An epic story of African victory over European colonizers

“I know the tactics of European governments when they wish to acquire possession of oriental states. They first send missionaries then Consuls to support the missionaries then armies to support the Consuls. I am not a Rajah of Hindustan to be hambugged in that fashion. I prefer having at once to do with the armies.” – Ethiopian Emperor Tewodros II.

Ethiopia holds a special place among African nations. This ancient country has a strong history of statehood, it has adopted Orthodox Christianity (which is rare for the African continent), and has retained its individuality to this day. One of the particular features of Ethiopia is that it persistently – and successfully – fought against European attempts to colonize it. In fact, Ethiopia is one of only three African countries (along with Liberia and Egypt, although the latter was under the British protectorate) never to have been colonized.

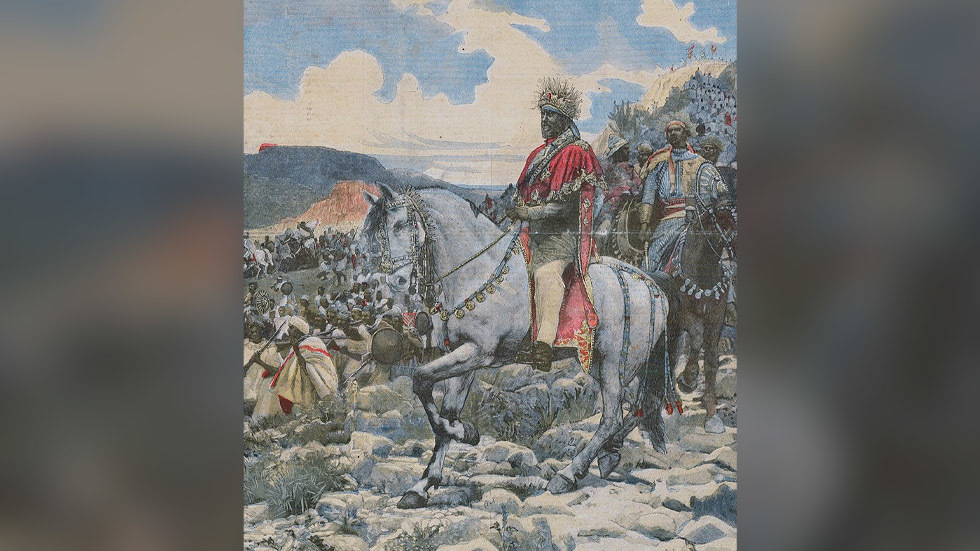

At the end of the 19th century, the army of the Ethiopian Negus (ruler) pulled off an amazing feat. It defeated a full-fledged European army in battle, and successfully prevented Europe’s attempt to forcefully impose its will on Ethiopia.

Swimming with crocodiles

For a very long time, Ethiopia had been a divided country. Its unification started only in the mid-19th century. At that time, the country was divided into separate lands and governed by feudal lords. The so-called subsistence economy provided only basic food, clothing, and shelter. There was no currency and people resorted to “primitive money”: pepper, salt, and most often, rifle cartridges, which were bartered for other goods.

No one liked this situation. The confusing customs and taxation system stifled the economy; in the north, the country faced pressure from Egypt, and the constant conflicts between the feudal lords posed risks within the country.

The person destined to unify Ethiopia was Kassa Hailu – a young man whose ascent to the throne no one could have predicted. He was born in 1818 into the family of a low-ranking feudal lord, and studied at a monastic school. When, in the course of a mutiny, the monastery was robbed, the schoolboy became a soldier. Kassa Hailu served in his uncle’s squad. Feudal strife helped him ascend to the throne – in 1855, having defeated several powerful rivals, Kassa won the final battle and became emperor of Ethiopia, taking the name Tewodros II.

He welded the country together by the “iron and blood” principle. However, his position was perilous from the outset. In the space of just a few years, he survived two dozen assassination attempts. Feudal lords rebelled throughout Ethiopia. Tewodros seized church property, causing the priests to turn against him as well. He also banned the slave trade, as a result of which rich slave traders became his enemies – or rather, funded his opponents. Nevertheless, Tewodros II carried out numerous state reforms, built roads, and reorganized the army. In fact, if it were not for external political forces, he could have gone down in history as a reformist tsar similar to Russia’s Peter the Great.

However, those were different times. Tewodros saw that his country had become part of a large and unfriendly world. Türkiye blocked Ethiopia’s access to the Red Sea. At first, the monarch planned to break through to the Red Sea, enlisting the support of Great Britain. However, in the 1850s, Britain supported Türkiye in the war against Russia, and this turn of events became fatal for the Emperor of Ethiopia. Tewodros made many rash decisions, got into a conflict with Britain, and failed to suppress an uprising in Ethiopia. As a result, he found himself surrounded by British troops from the sea, and by rebels within the country. In 1868, interventionists and rebels stormed the citadel of Magdala, and in order not to surrender, Tewodros shot himself.

However, the trend towards the unification of Ethiopia, which Tewodros had initiated, continued. In 1872 the leader of Tigray region ascended to the throne as Yohannes IV. An ascetic, energetic, and strong ruler, he preserved and multiplied the positive achievements of Tewodros. Yohannes IV repelled the Egyptian invasion, resolved domestic policy issues, and managed to come to an agreement with the opposition and reconcile opponents. His success seemed brilliant. However, at this time an unexpected enemy suddenly emerged: Italy.

The start of Italian colonial expansion

Italy became a single state only in the 19th century, and for this reason was late to join the colonial race. However, it intended to quickly catch up with the other European powers. Ethiopia found itself in an unforeseen diplomatic trap: the British wanted to limit the colonial expansion of France in Africa, and so reacted favorably to Italy’s attempts to capture the Red Sea coast. For Britain, Italy was supposed to become a counterweight to France.

Rome proceeded with the expansion cautiously and tried to gain the support of the rulers of Ethiopia’s Shewa region. Shewa was part of the empire of Yohannes IV but it was a troubled and autonomous region.

In 1885, after the Italians captured the towns of Saati and Massawa, they founded a colony called Eritrea on the Red Sea coast. In 1887, the Ethiopians defeated an Italian detachment which headed to Saati through Dogali. Ethiopian fighters used semi-guerrilla warfare tactics, common for the weaker side, and carried out ambush attacks.

The Ethiopians were quite enthusiastic about the victory near Dogali – it turned out that the Europeans were far from “unconquerable.” However, that was only a small European detachment of several hundred troops. At that time, Ethiopia tried to pursue a cautious policy, especially since Italy enlisted the support of the ruler of Shewa, Menelik. Moreover, Ethiopia became involved in a futile war with Sudan. In short, the situation was difficult.

Yohannes fought on many fronts and was eventually mortally wounded during the battle with the Sudanese Mahdiyya. However, the banner was immediately taken up by Menelik II of Shewa – and although his relations with the former ruler weren’t the best during the latter’s lifetime, Menelik continued Yohannes’ work.

Menelik seized power in Ethiopia, and revived this ethnically diverse, unstable country. For many years, Menelik had been a political hostage at the court of Tewodros II, and later he put a lot of effort into strengthening the economy of his own domain – his main priorities were the calm and stability of his region. He turned out to be a flexible leader. For example, in an attempt to take control of Harar, which was an important trading center, the Emperor wrote to the city’s ruler: “I have come to reclaim my country, not to destroy it. If you obey, if you become my vassal, I will not deprive you of the right to rule. Think about it so you have no regrets later.”

Two different translations

In 1889, Menelik II became Emperor of Ethiopia, and started rebuilding the country. Years of civil war had weakened the power of the feudal lords, and now he could carry out many modern administrative reforms. In place of the former feudal lands, he created provinces which were headed by governors appointed by the capital. Sometimes, Menelik showed flexibility and left the former rulers in place, but the authority to govern the region was given by the Emperor, and not by right of blood or use of force.

With these reforms, Menelik had considerably reduced the risk of uprisings. Another important innovation was the establishment of a permanent capital, Addis Ababa (“New Flower”), which is the capital of Ethiopia to this day. From the new capital, Menelik sent a letter to the European powers, in which he proclaimed his territorial ambitions and outlined the borders of Ethiopia. In general, Menelik was a good ruler. But there were those who didn’t like what he did.

Italy was one such country. At first, relations between Addis Ababa and Rome were quite warm – Italians had initially supported the Shewa region, and now, they assumed that the whole of Ethiopia would become an Italian colony. However, Menelik had other plans. The difference in views soon became apparent and the events unfolded dramatically. In 1889, Ethiopia and Italy concluded an agreement in the town of Wuchale (the Treaty of Wuchale, or ‘Uccialli’ in the Italian version). The problem was that the text of this agreement in Amharic (the official language of Ethiopia to this day) and Italian was slightly different. The Amharic version said that the Emperor of Ethiopia may turn to the Italian government for mediation in negotiations with other countries. But in the Italian version, instead of “may” it was written “must.” Italy immediately notified other European courts about its new possession, but Menelik found out how the treaty was interpreted in Europe only after Queen Victoria of England informed him that she would send a copy of his letter to Rome.

Menelik was furious. Meanwhile, Italy was already preparing to tighten its grip in Africa. The role once assigned to Shewa – that of Italy’s “Trojan horse” – was now given to the Tigray region in northern Ethiopia. However, Menelik reacted to these plans quickly and harshly. Italy realized that the Ethiopians would not give up, and began preparing a wide scale military expedition.

General Baratieri’s mistake

The Italians captured those Ethiopian cities and fortresses where the local forces didn’t put up serious resistance. First of all, this was the Tigray region, which agreed to conclude an agreement with Rome. However, Menelik was already planning a retaliatory strike.

For a decade prior to those events, Ethiopia had been actively purchasing European weapons. From 1885 to 1895, almost 190,000 firearms were imported into the country –these were shotguns, rifles, and revolvers. 40,000 firearms were also bought from Russia in 1895 with the aid of the Kuban Cossack Army headed by Nikolai Leontiev, who personally arrived to help Menelik with a group of volunteer officers and medical personnel.

Menelik quickly formed an army. For their part, the Italian commanders didn’t give the matter much thought – they believed they would be fighting against militias armed with spears and bows.

In September 1895, Menelik announced the start of combat. “Help me, those of you with zeal and will power; those who do not have the zeal…help me with your prayers,” he said.

Soon afterwards, the Ethiopian armed forces attacked the Italian garrisons. In December, they attacked the garrison in Amba Alagi. The Italian detachment numbered 2,500 men, while the Ethopians advanced with a 15,000-strong army and instantly defeated the Italians. The garrison in Mekelle surrendered, and was allowed to retreat and even keep its weapons.

General Oreste Baratieri commanded the 17,000-strong Italian army and fought against Menelik’s army. However, the Ethiopian forces were several times stronger. In fact, Baratieri was deceived – he considered the enemy a bunch of savages, instead of relying on facts about Menelik’s army. Given that Menelik had a well-trained intelligence service, it was like a battle between the blind and the sighted – and moreover, the latter had strong muscles.

Adwa

On February 25, 1896, Baratieri took decisive action. The main battle between the two armies took place on March 1, in the city of Adwa.

Baratieri advanced with three brigade columns, and kept another one in reserve. Marching at night, he intended to occupy the elevation in front of the Ethiopian army’s positions. If this plan had succeeded, Menelik would have found himself in a very difficult position. However, the march was poorly organized – the columns moved in a disorganized manner and quickly lost contact with each other. Baratieri encountered problems everywhere. The combat capability of the Italian army was low, many soldiers were assigned to African units as punishment. In fact, there were only 11,000 Italian soldiers, and another 6,700 fighters were recruited in Africa. The level of discipline in the army was low. The same could be said about Menelik’s army, but he had over 100,000 men, and about 80,000 of them with firearms.

In fact, Baratieri had lost the main battle of the war before it even started, but he didn’t know that yet.

By 3:30 a.m. on March 1, one of the Italian brigades (which included African fighters who knew the area) under the command of General Albertone reached the hill where they were supposed to be positioned, but soon discovered that it was the wrong location and the position was somewhere ahead. The brigade commander did not bother to tell Baratieri where he was going, and simply marched on. Around 6 a.m., the Ethiopians attacked the brigade and pushed it back. The Italian gunners fought bravely and many died on the spot. The remaining troops were encircled and surrendered.

The central group of the Italian army was attacked by the main forces of the Ethiopian army. The remaining soldiers of the Albertone brigade reached the positions of the Italian detachments and blocked the line of fire for their own artillery. Ethiopian units followed them, soon caught up with the Italians, and attacked them.

The Italian brigades were practically swallowed up by Ethiopian forces. The order to withdraw came too late. After 12:30 p.m., there was no longer anyone in command of the army. The remaining brigades put up a stubborn resistance, but their defeat was only a matter of time.

The remaining Italian troops fled. Of the four brigade commanders, two were killed and one was captured. About 8,000 troops were killed or captured, about 1,500 men were wounded, and the army lost 11,000 rifles and all its artillery.

The Ethiopians lost many men as well. After all, the Italians attacked them with quick-firing guns. According to some estimates, 6,000 Ethiopians died and 10,000 were wounded (the reliability of this data is uncertain). However, considering the fact that the Ethiopian army greatly outnumbered the Italians, the losses weren’t too bad for the Ethiopian side.

Victory and its results

When news of this defeat reached Italy, it caused a government crisis. Ethiopian troops advanced north, pushing the Italians to Eritrea – territory on the Red Sea coast which was then under Italian control (the modern-day State of Eritrea).

Menelik did not intend to completely push the Italians out of Africa. The Eritrean population was known for disloyalty, and Menelik feared that claiming this territory would only strengthen the opposition forces within Ethiopia.

However, the Emperor wanted to get the most out of his victory, and Menelik made Rome conclude a peace agreement. It was signed on October 6, 1896, and practically meant that Italy threw in the towel – Ethiopia’s independence was fully recognized without any restrictions, and Italy pledged to pay war reparations. For its part, Italy retained some lands in Africa – but in fact, everyone knew that this was favorable for Menelik.

Ethiopia’s subsequent history was somewhat stormy, but at the time, it managed to fight for and defend its independence. In the years ahead, Ethiopia was involved in agonizing civil confrontations and during WWII, it fought on the side of the Allies – but the victory of 1896 remained engraved in its history as a brilliant triumph in the long struggle for unity and freedom.