Western financing only worsens Africa’s development prospects. In 2009, Zambian economist and former World Bank consultant Dambisa Moyo defined such assistance as “dead aid.”

Following the rise to power of a new generation of African leaders and the creation of the Alliance of Sahel States, Africa’s sovereign economic development has once again become a relevant issue. Moreover, the center-periphery model of development – with the West as the center – may be revised. This model has been in place since the 1980s, when Western financial institutions implemented structural adaptation programs in Africa that forced the state to withdraw from the social sphere and entailed the liberalization of industries.

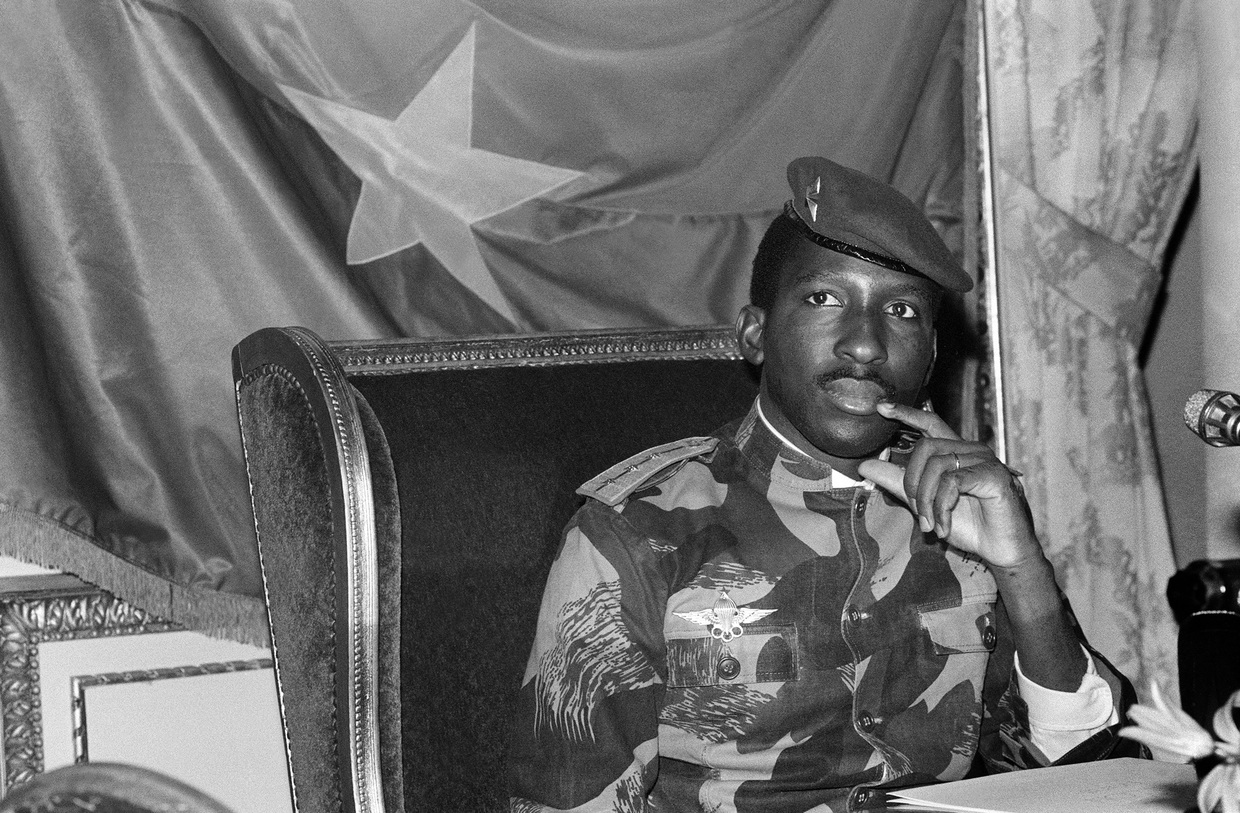

Reforms of ‘Africa’s Che’

The socio-economic reforms of Thomas Sankara, president of Burkina Faso from 1983-1987, seem incredibly bold by modern standards. They were carried out at a time when neighboring socialist-oriented countries were gradually becoming involved in IMF programs, and although the USSR still provided major assistance to Africa, the Soviet Union had already embarked on a path of “soft convergence” with the West. We’ve talked quite a lot about Sankara as “Africa’s Che Guevara,” but his socio-economic reforms in particular seem to be underestimated.

In Burkina Faso, the problem wasn’t just relations between the center and periphery, but rather “center-periphery-periphery”-type relations. Burkina Faso’s economy acted as the periphery of Ivory Coast’s (Côte d’Ivoire) economy and supplied it with a labor force, while the latter was integrated into the global economy as a “reliable supplier” of an important commodity – cocoa.

Paradoxically, despite the scope of the socio-economic reforms that Sankara planned (and largely managed to implement), he preferred self-reliance and ordinary people’s ‘emotional mobilization’ rather than massive external assistance.

In a speech in August 1984 titled ‘There is Only One Color – That of African Unity’, Sankara directly answered those who asked what he thought about international aid. He said, “Aid must go in the direction of strengthening our sovereignty, not undermining it. Aid should go in the direction of destroying aid. All aid that kills aid is welcome in Burkina Faso. But we will be compelled to abandon all aid that creates a welfare mentality. That’s why we’re very careful and very exacting whenever someone promises or proposes aid to us, or even when we’re the ones taking the initiative to request it.”

He opposed not only Western aid as such, but also “imported” models of African development, noting the “terrible consequences of the devastation imposed by the so-called specialists in Third World development” and rejecting “externally driven development agendas.” Essentially, he advocated for the “decolonization” of Africa’s development process.

In the 1970s, researcher Johan Galtung noted the psychological aspect of abandoning “tastes generated from the center and satisfied with center goods only” for the sake of sovereign development and “independent taste-formation.” He believed that the transition to such models “is located more in the field of psycho-politics than in the field of economics.”

Sankara, who sought the advice of the leading intellectuals of the time, focused on such ‘psycho-political’ decolonization even before becoming the country’s president – he set out on this course in September 1981, when he became the secretary of state for information.

The people of Burkina Faso still remember the slogan of that era: “Consume what you produce and produce what you consume!” and proudly wear clothes made from locally-produced Faso Dan Fani fabrics.

Good old self-reliance

Former Tanzanian President Julius Nyerere used a similar concept of self-reliance within the framework of the Tanzanian socio-economic model ‘Ujamaa’. He persisted in these efforts as long as external circumstances allowed. However, in the mid-1980s, after the onset of the TINA era (an acronym for ‘There is no alternative!’, the slogan used by Margaret Thatcher about the inevitability of liberal reforms), Nyerere was forced to resign, so as not to personally destroy the model of self-reliance that he had built with such care.

Even in those times, experts noted that this model was rooted in African traditions and surpassed not only “scientific socialism” but also “African socialism” associated with the conciliatory policies of Leopold Senghor and Tom Mboya – politicians who represented the “showcases of capitalism” in the French-speaking and English-speaking parts of Africa: Senegal and Kenya, respectively.

Although the traditions of self-reliance were quite strong in Tanzania, in the 1990s-2000s in neighboring Kenya a similar concept was discredited (declared equal to corruption) and eventually officially banned as a result of a study conducted by the British (!) company Risk Advisory Group.

All of these development models may be generally defined as self-reliance models. Coincidentally, even European researchers have noted that this approach may be promising, both at the country level and in regard to reforming the global governance system. This is exactly what BRICS is trying to do today by strengthening the structural power of the non-Western world and forming a global agenda that is more aligned with the expectations of the Global South.

The self-reliance concept may be implemented at several levels: locally, nationally, and regionally. For African countries, the most relevant issues today include resuming the provision of social services (local); building strategies for the development of individual Sahel countries (national); and focusing on collective self-reliance within the framework of the Alliance of Sahel States (regional). The fourth level would be to abandon the concept of the so-called Third World – as during the era of active South-South cooperation and economic partnership within the Non-Aligned Movement – in favor of the non-West or world majority. In this regard, the geography of the trips recently taken by Nigerian Prime Minister Ali Lamine Zeine is noteworthy – in January 2024, he visited Russia, Iran, Turkey, and Serbia.

Self-reliance is particularly important for food security, since the supply of tropical agriculture products to the EU (which ensures the food security of the EU) comes at the expense of Africa’s own food security. The cost of Africa’s food imports is expected to double by 2030, reaching $110 billion.

In this regard, collective self-reliance is highly important, since the size of the national economies of individual African countries often doesn’t allow them to implement sovereign policies in a wide range of fields.

Other countries and integration groupings look up to the Alliance of Sahel States as a positive case, since most African regional economic communities are based on regional trade liberalization and in fact, undermine national industrial development strategies.

What’s wrong with international aid?

In Soviet books on Africa, whenever international aid was mentioned, the word was always put in quotation marks (i.e. so-called “international aid”). The Soviet Union condemned the West’s hypocrisy, since on the one hand, African countries received certain annual assistance from the West, but on the other hand, the continent experienced massive capital flight.

Addressing young people (among whom there were many Africans) during the World Youth Festival in Sochi in March 2024, Russian President Vladimir Putin said, “In the course of [Russia’s] numerous contacts with African leaders, even from those countries where the economic situation is very difficult, people’s lives are very hard and [the population is] often malnourished, never – and I emphasize this, never – has anyone asked us for anything directly. No one stretched their hand out and said – give us this, give us that. Everyone only spoke about establishing fair, honest joint economic cooperation.”

It’s not a coincidence that many countries of the Global South, primarily BRICS members, are trying to break free of the hierarchical donor-recipient relationship characteristic of North-South assistance programs. They prefer to discuss solidarity and mutual cooperation – but not “aid.”

As a rule, Western aid comes with many conditions and political demands. The donor-recipient relationship often violates the principle of sovereign equality, the recipient’s rights are limited and the concept of “good governance,” which requires the presence of the “right institutions” to implement liberal reforms, is not that different from colonial administration.

The conditions imposed also limit a country’s economic sovereignty, since they narrow the range of possible economic policies and strategies to combat poverty, and they reduce the state’s ability to control international trade and investment flows.

The collective West coordinates its requirements through the Development Assistance Committee (DAC) of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD, the economic equivalent of NATO). On a local level, in recipient countries coordination takes place during regular meetings of Western donors at EU or World Bank delegations. In particularly challenging cases, the DAC OECD members issue a consolidated ultimatum to the recipient countries.

The Western-centric system rigidly controls not only who receives the aid, but also who provides it. As US allies and vassals, Bretton Woods institutions – the IMF and the World Bank – remain the largest donors, although in recent years, China has become their major competitor within the Belt and Road initiative.

Are there alternatives?

Several African countries still continue to implement “imported” national development strategies elaborated by neocolonial think-tanks such as the Institute of Development Studies (IDS) and the Overseas Development Institute (ODI) for the former British colonies, or the French National Research Institute for Sustainable Development (IRD) for the former French colonies.

Since colonial times, these institutions have advocated a “pseudo-development matrix” for African countries that only increases their dependence on the West and is financed within Western “international aid” programs. When it comes to national development, only sovereign expertise will allow African countries to abandon the path of dependent development.

During the power transition period (from Western to non-Western actors), the role of the “middle powers” becomes increasingly important. This includes countries such as Türkiye, which does not agree with the role assigned to it by the West and pursues its own aid policy, which differs from that of European countries.

China has never been part of the OECD Development Assistance Committee and has played a key role in demonopolizing international aid flows by putting forward economic rather than political conditions when providing assistance to Africa.

Since 2022, cooperation between Russia and the OECD has ceased, and Russia is no longer considered a donor which lost the Cold War while pursuing a sovereign cooperation policy with African countries.

Partnership between Africa and countries of Islamic world is also growing, particularly since many of them joined BRICS (e.g. the UAE, Iran, and Egypt).

In what may be considered the second wave of the “awakening of Africa,” African countries themselves are gradually moving away from the TINA model and political conditions that clearly contradict African values. In February 2024, Ghana, which has long been considered a “good recipient” by Western donors, passed a law condemning the spread of LGBT propaganda. This is just one case of the country’s large-scale efforts to pursue a course of sovereign development.

This means that when it comes to international aid – and on a wider scale, setting priorities for global development – the Western monopoly is clearly coming to an end.