In May, Nigeria’s President Bola Tinubu signed into law a bill that restored the country’s old national anthem from when it gained independence from Britain, “Nigeria, We Hail Thee,” sparking widespread debate and concern. The move, executed with unprecedented legislative speed, marks a significant and controversial shift from “Arise, O Compatriots,” which had been the national hymn since 1978. The decision, ostensibly aimed at rekindling a sense of national unity, has instead stirred a hornet’s nest of controversy, reflecting deep-seated tensions about national identity, colonial legacies, and governance.

Colonial Echoes

In the annals of Nigerian history, few symbols evoke as much passion and controversy as the national anthem. The name Nigeria itself, a colonial construct of Western imperialism born out of the Berlin Conference of 1884-1885, carries the weight of a complex heritage. What became Nigeria was coined by Flora Shaw, a British journalist with “The Times” and a staunch advocate of imperialism. The formation of the name was a way to describe the “Niger Area,” a territory administered by the Royal Niger Company. She eventually married the British colonial governor Fredrick Lugard, whose name is a reminder of the country’s colonial past.

The story of Nigeria’s national anthem begins at the dawn of its independence. Adopted on October 1, 1960, “Nigeria, We Hail Thee” bore the unmistakable imprint of its colonial origins, with the authorship reflecting the perspective shaped by the colonial context in which they lived.

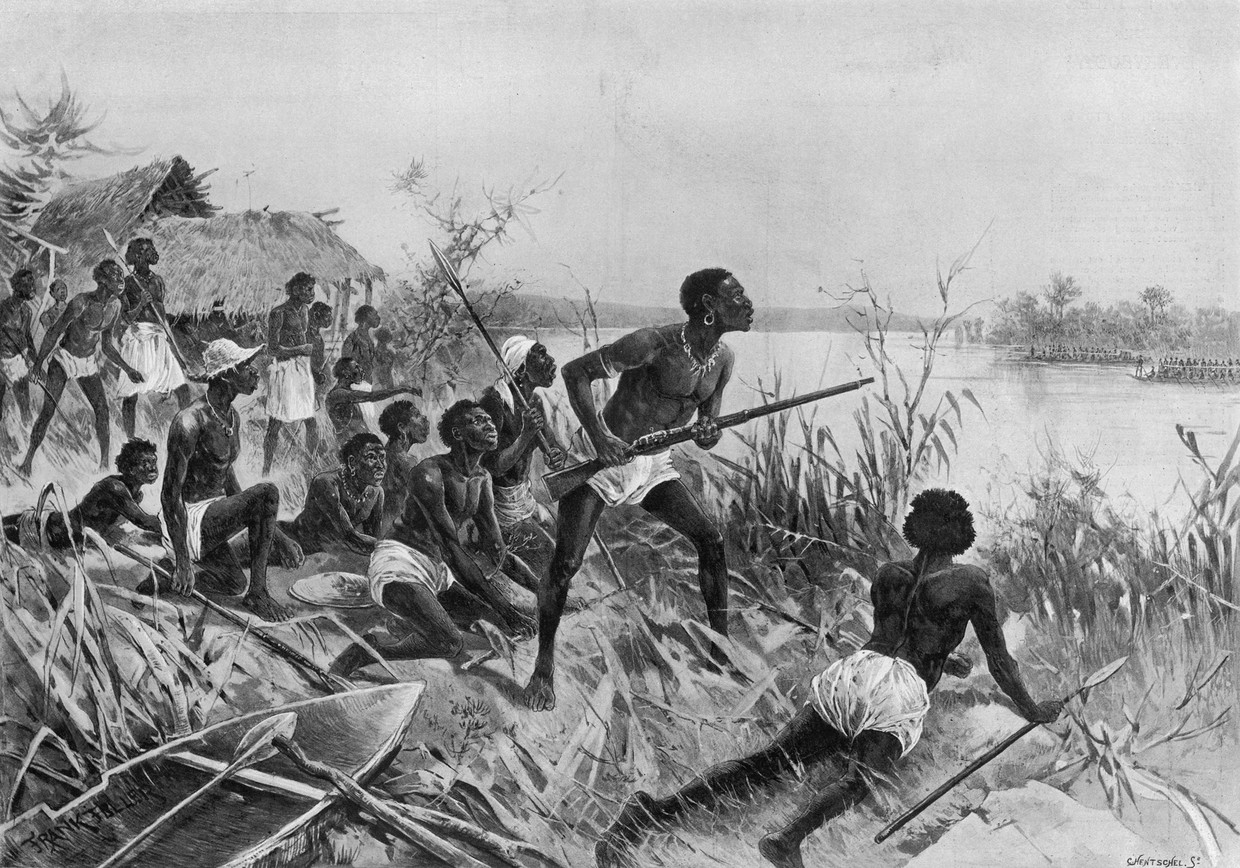

The anthem, written by a British expatriate Lillian Jean Williams, and composed by her compatriot Frances Berda, was seen by many as a relic of colonial influence. Beginning with the formality of tone and language, instances can be seen in the stanzas “O God of all creation” which reflect the effects of British colonial Christianity. Africa had its own traditional religion before Christianity was introduced by the British and gradually, it witnessed the greatest scramble for resources ever seen. Archbishop Desmond Tutu, the human rights activist well known for his role in ending apartheid, once said: “When the missionaries came to Africa they had the Bible and we had the land. They said ‘Let us pray. ‘ We closed our eyes. When we opened them, we had the Bible, and they had the land.”

However, the adoption of the colonial anthem was emblematic of the transitional phase Nigeria was in, moving from colonial rule to self-governance.

The first change, in 1978, initiated under the military regime of General Olusegun Obasanjo, was a response to growing demands to shed the remnants of the colonial legacy. The new anthem, “Arise, O Compatriots,” was a collaborative creation by five Nigerians. The anthem quickly became a symbol of a new Nigeria, seeking unity after the brutal Biafran conflict, also known as the Nigerian Civil war 1967-1970 between the Nigerian federal government and the secessionist state Biafra over marginalization of the Eastern region.

The new anthem sought to heal a nation, celebrating unity, peace, and patriotism. It emphasized the need for every Nigerian to contribute to nation-building, resonating with the spirit of a country trying to heal and rebuild. In contrast to the colonial anthem, “Arise O Compatriot” it reflects the post-colonial ideals free from colonial influence:

Arise, O Compatriots,

Nigeria’s call obey

To serve our fatherland

With love and strength and faith.

It represents a collective call to action and national unity which resonates with the nationals. Over a million people died during the country’s civil war; while some lost their lives fighting, many died from starvation and disease. So, when the authors wrote, “the labor of our heroes past shall never be in vain”, they called for remembrance of the lives lost during the conflict.

Reversion to Old-New Colonial Anthem

Fast forward to 2024, and Nigeria finds itself at another crossroads. President Tinubu’s decision to revert to “Nigeria, We Hail Thee” has been met with a mix of nostalgia and backlash. Analysts ave pointed to the unusual speed of the decision-making in parliament and worry it could set a precedent for more significant changes being pushed through without adequate public scrutiny.

Proponents argue that the old anthem evokes a deeper emotional connection and symbolizes Nigeria’s diversity. They contend that the current anthem, a product of a military regime, does not adequately reflect the democratic aspirations of the Nigerian people. President Tinubu, who had previously expressed a preference for the old anthem, in an interview back in 2022 said: “If I had my way, I would bring our first national anthem that describes us better. It’s about service, diversity, and commitment to value our nation-building. We must guard our democracy jealously because we are one Nigeria. And we should be proud of our past”.

However, many view the decision as a distraction from pressing issues like rampant inflation and rising insecurity. Critics see the change as a regression, a step back to a colonial mindset. Indeed, one of the reinstated anthem’s authors, Dr Sota Omoigui, told a local Nigerian newspaper that “The colonial anthem was the right anthem at that time in our history. A nation should always move forward and not backwards. Arise O Compatriots is an anthem with lyrics written by Nigerians and music composed by a Nigerian. Our culture, music, movies, songs and dance are exported and celebrated by different races all over the world. Radio stations and clubs in cities from Alaska to Argentina play Nigerian Afrobeat. Yet in the birthplace of that culture, the leaders reject their own anthem for a colonial anthem. Nigeria, the hitherto giant of Africa that led the liberation struggles of Africans to defeat apartheid and colonialism is now reduced to a midget crawling back and crying “mama” to her colonial master.”

While “Nigeria, We Hail Thee” nostalgically recalls the optimism of independence, its colonial authorship and outdated language may fail to inspire a contemporary generation attuned to global dynamics and digital connectivity. The debate around Nigeria’s anthem is more than a matter of lyrics; it reflects the nation’s ongoing struggle to define its identity post-colonialism.

Constitutional Absurdities

The controversy surrounding Nigeria’s national anthem highlights the nation’s ongoing struggle with its identity, governance, and a need to balance its colonial history with its aftermath.

The reversion to the old anthem without broad public consultation exemplifies what some see as the absurdities of Section 2 of the 1999 Constitution which states that “Nigeria shall be one indivisible and indissoluble Sovereign State to be known by the name of Federal Republic of Nigeria “. This however echoes the 1979 Constitution in ascribing sovereignty not to the people, but to the state. It legitimizes a ruling elite that often acts more like a landlord, with the populace in the role of tenants. In a country where many feel disenfranchised, this move has only heightened feelings of alienation and resentment.

At the heart of this debate lies a fundamental question about the national identity of the country built around over 250 ethnic groups, and shared values. A national anthem is more than just a song; it is a reflection of a country’s collective memory, aspirations, and values. “Nigeria, We Hail Thee,” with its call for unity despite tribal and linguistic differences, and “Arise, O Compatriots,” with its focus on freedom, peace, and unity, both aim to inspire patriotism and a sense of national purpose. However, the contexts in which these anthems were created and adopted are vastly different, influencing their reception and significance.

The decision to revert to the old anthem has been met with sharp criticism from various quarters. Prominent voices of protest have emerged, such as former Minister of Education Oby Ezekwesili, who labelled the adoption of the new-old anthem as an “obnoxious law and repugnant to all who are of good conscience in Nigeria.” “With all the horrible indicators on the state of governance? So, is a new National Anthem their priority? I frankly thought it was a joke and gave it no attention. What an egregious case of ‘Majoring in the Minor’ this is!” she wrote.

Reuben Abati, a journalist, described the move as a tactic to divert public attention from the government’s unpopularity and the country’s dire economic situation. “One of the very easy tactics that a government adopts when it sees that it is unpopular with the publics that it governs is to create a diversion, fly a kite or invent a subject of controversy to keep the people busy and draw them away from what exactly they should be talking about”, he told a local news platform.

On the other hand, Senate President Godswill Akpabio and others justify the return to the old national anthem, described it as one of the most significant things achieved during Tinubu’s first year in office and see it as a rallying call for unity and a reminder of Nigeria’s diverse yet interconnected heritage.

“Of all the significant things you have done, I think one of the most important is to take us back to our genealogy; the genealogy of our birth. That though we may belong to different tribes, though we have different tongues, in brotherhood we must stand. Whether in the field of battle or politics, we must hail Nigeria. The best place to start this revolution is the National Assembly where we have the elected representatives of the people”, Godswill Akpabio told a local newspaper.