‘Africa must unite’: Why this man was feared by the US and Britain

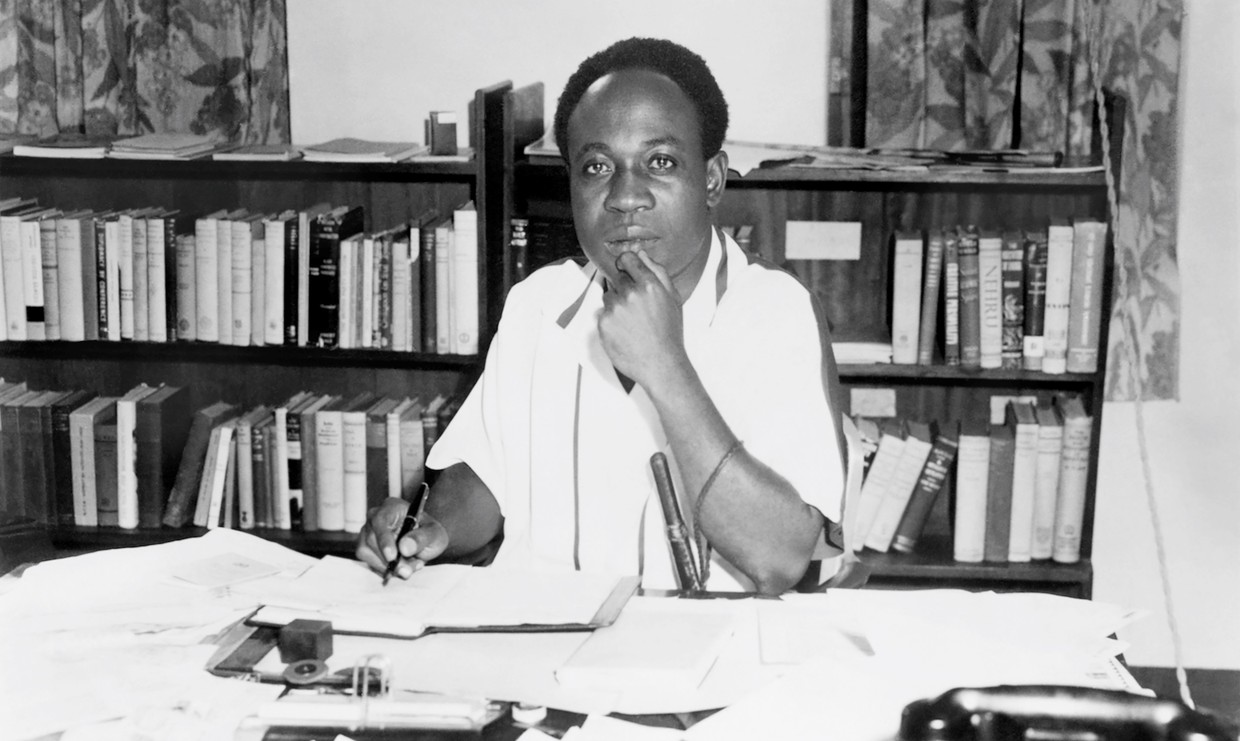

Kwame Nkrumah, the first prime minister of the first sub-Saharan African country to gain independence, was a towering figure in the struggle for self-governance in Africa. An ardent proponent of pan-Africanism and a formidable political theorist, he is credited with being the first to apply the term ‘neo-colonialism’ to Africa’s 20th century experience, correctly anticipating that European powers would use various levers to keep former African colonies in a state of de-facto dependency even if formally independent. His ouster in a 1966 CIA-backed coup, however, also serves as a stark reminder of the forces aligned against African liberation.

The man who would take the helm of an independent Ghana was born on September 21, 1909 in Nkroful, a town in the Gold Coast (now Ghana) as Francis Nwia-Kofi Ngolonma. He later changed his name to Kwame Nkrumah.

He pursued teacher training in Ghana, after completing his basic education in the town of Half Assini. He then moved abroad to continue his studies at Lincoln University in Pennsylvania, and later at the London School of Economics. His stay in the US was marred by racism and financial constraints – and yet was also a time of intellectual ferment.

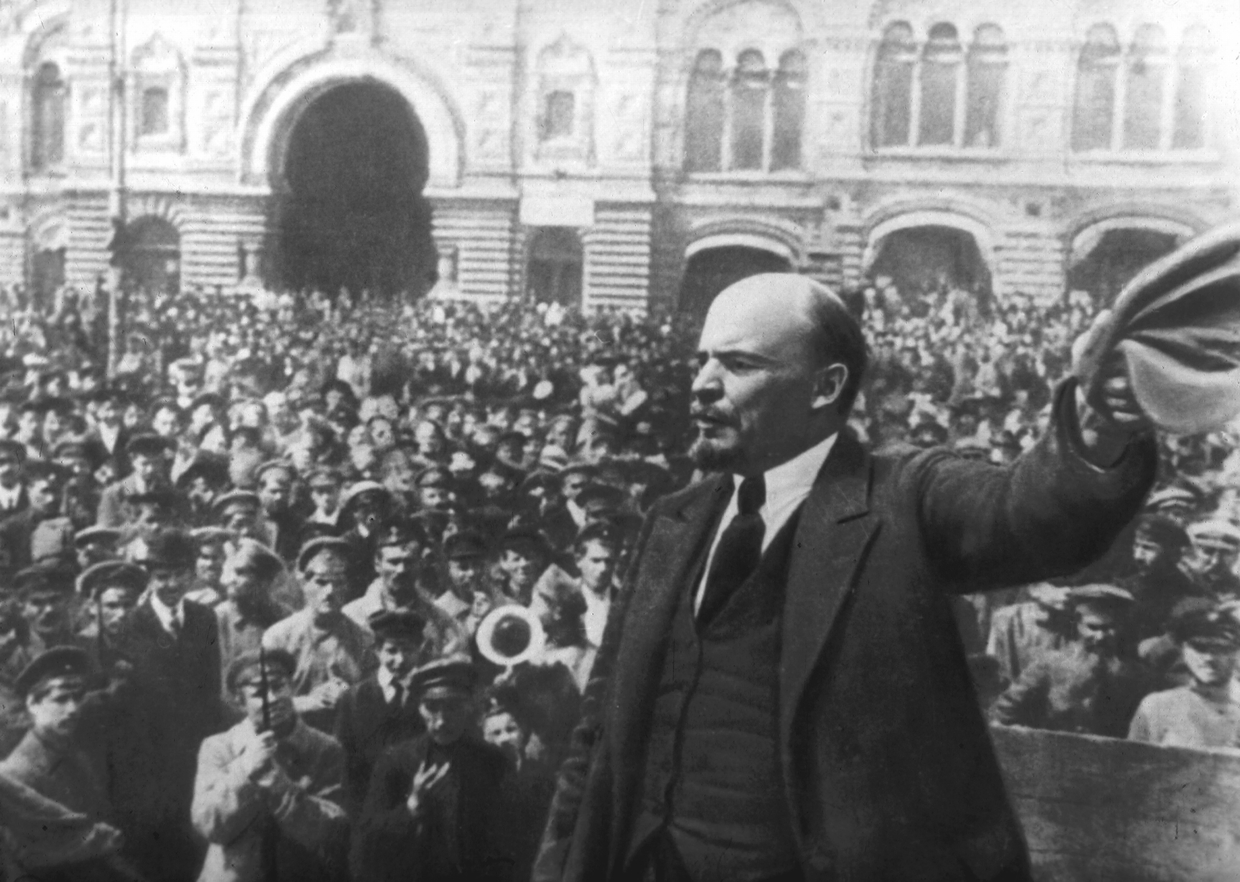

During his studies, Nkrumah took an interest in the writings of Lenin, Marx, and Engels. This ideological connection is evident in his book from 1965 ‘Neo-Colonialism, the Last Stage of Imperialism’, a reference to Lenin’s ‘Imperialism, the Last Stage of Capitalism’ published in 1917. It was a book that infuriated the British.

Well-versed in philosophy and political theory, Nkrumah referred to himself as a non-denominational Christian and a Marxist-socialist. He believed socialism addressed the question of liberation from imperialism but argued that, despite achieving formal independence, many economic structures remained in place that prevented Africa from being developed for the benefit of Africans themselves.

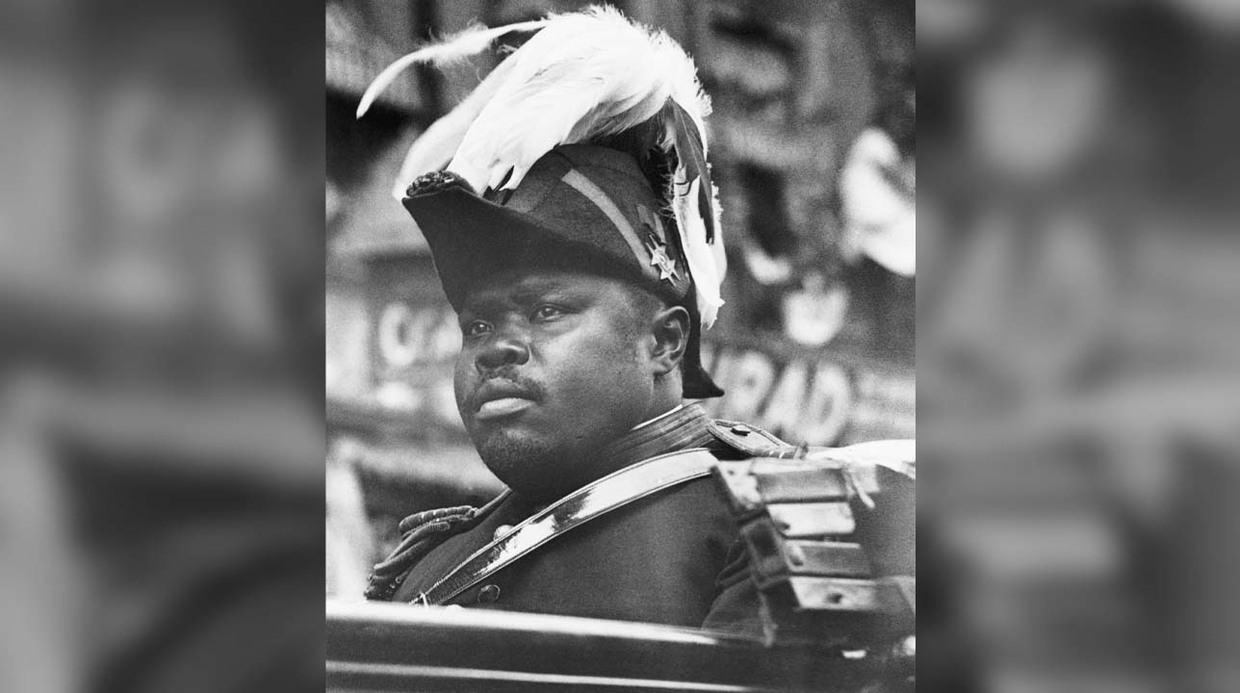

Meanwhile, the question of how to effectively organize politically remained unanswered, so Nkrumah acquainted himself with the activities of various political liberation organizations, such as Marcus Garvey’s Back to Africa movement in the US and the West African Students Union in London.

The rise of the elites

The end of World War II and the adoption of the principles of sovereignty and self-determination in the United Nations charter in 1945 inspired Africans to pursue independence and self-rule. In Ghana, there was a significant ideological shift among the educated elites. Dissatisfied with British colonial rule, they formed a political party known as the United Gold Coast Convention (UGCC) in 1947, which called for greater political representation, an end to economic exploitation, and independence within the shortest possible time.

To achieve its aims, the party needed intellectuals who could galvanize the masses and champion these ideals. One leader who stood out was Kwame Nkrumah, who helped establish the African Students department at the University of Pennsylvania and had helped build the university’s African students organization into the African Students Association of America and Canada.

Thanks to his intellect and experience in political activism, Nkrumah was invited back to Ghana in 1947 to become the general secretary of the UGCC.

From prison to the Big Six

Shortly after his arrival in 1948, peaceful protests broke out in the Gold Coast following the British colonial government’s reluctance to pay ex-servicemen who had fought on behalf of Britain in World War II, and also due to high inflation and limited political representation of Ghanaians in public affairs. The British colonial government shot to death three ex-servicemen who were peacefully marching to the Cristianborg castle, the seat of the colonial government, to present their petition. They also arrested Nkrumah together with five other members of the UGCC for allegedly fueling the protest.

While in prison, the members of the UGCC grew increasingly hostile toward Nkrumah, blaming him for their misfortune.

However, the protest forced the British colonial government to conduct legislative reforms, a move that led to the adoption of a constitution in 1951 that provided broader electoral representation for Ghanaians. Nkrumah and his party members were vindicated, released from prison in April 1948, and became known as the Big Six.

Election triumph

Whereas the UGCC had become more conservative regarding the independence struggle, Nkrumah’s radicalism coupled with his prison experience put him out of step with the party. Consequently, he broke away from the UGCC and formed the Conventions People’s Party (CPP) in 1949 with the motto: “self-government now.”

Nkrumah organized a non-violent civil operation involving strikes and boycotts in January 1950 to demand immediate self-rule. The colonizers depicted this as a threat to the rule of law and imprisoned Nkrumah again in December 1950. However, his actions appealed to the masses, who were fed up with the colonial dictatorship and desired an immediate and radical shift to self-rule. This support won Nkrumah a seat in the general elections in February 1951 even while he was in prison (the colonial government at the time did not bar prisoners from running for office). The CPP then nominated him for the Accra Central constituency, capitalizing on the political oppression by the colonial government to appeal to the masses. Nkrumah won the election by a wide margin.

The colonial government was then forced to release Nkrumah, allowing him to become the leader of government business. In 1952, he became the prime minister and in 1960 he took over as the first president of the Republic of Ghana.

“The strength of the imperialist lies in disunity”

On March 6, 1957, Ghana under Nkrumah declared independence. However, Nkrumah was not convinced that Ghanaian independence was relevant if other African countries were still under colonial rule. Consequently, he stated in his Independence Day speech: “The independence of Ghana is meaningless unless it’s linked to the total liberation of the African continent.”

Nkrumah’s vision of African unity had evolved from a concept of Pan-Africanism championed by civil right activist W.E.B. Du Bois and Jamaica-born activist Marcus Garvey in the US, and by C.L.R. James and George Padmore, both from Trinidad, in Britain in the 1860s. Pan-Africanism was aimed at promoting African cultural values and fostering unity among people of African descent in those countries. Therefore, the concept wasn’t new, but Nkrumah popularized it in Africa itself in 1958 when he organized the first inter-state All-African People’s conference in Accra, Ghana.

At the time, the UN did not recognize colonies under colonial rule as states in making important global decisions. Nkrumah, however, believed that liberating African states first required recognizing African leaders as important decision makers. A notable example was Patrice Lumumba who was invited to the 1958 conference in Ghana. Two years later, Lumumba, inspired by the conference, led the Congolese National Movement to achieve independence from Belgium.

Nkrumah’s concept of African unity was not to create a single country out of the African continent but to unify certain sectors that could make Africa competitive globally. He championed a common foreign policy, currency, monetary zone, central bank, and security architecture for African states based on African socialism and neutrality toward the Cold War powers. Politically, this goal was born out of fear that individual African states could enter into security agreements with foreign countries outside Africa, and thus the continent would sink into proxy wars on behalf of others.

However, his concept of African socialism was a direct response to the operation of the colonial powers which, through cartels, dictated prices for goods in most African states due to the monopolies they exercised in commerce. In 1963, Nkrumah published a book titled ‘Africa Must Unite’, which encapsulated his vision for a unified Africa.

Nkrumah’s vision attracted the interest of Julius Nyerere of Tanzania, Lumumba of Congo, and other African leaders. Consequently, in the same year, they combined forces to form the Organization of African Unity (OAU), the forerunner of the African Union.

“We face neither East nor West: We face forward”

However, Nkrumah’s anti-imperialist ideas were increasingly perceived as a threat by the colonial powers, including, by that time, the US. In 1964, Mahoney Trimble, the US State Department director for the office of West African Affairs, proposed an action program for Ghana.

The plan entailed overthrowing the democratically elected Nkrumah through US pressure with assistance from Britain: “U.S. pressure, if appropriately applied, could induce a chain reaction eventually leading to Nkrumah’s downfall. Chances of success would be greatly enhanced if the British could be induced to act in concert with us.”

There was a great fear in the US of ‘leftist elements’ in Ghana: “The U.S. should make a determined effort to remain in Ghana. Voluntary withdrawal of our representation would be interpreted both there and elsewhere in Africa as a defeat for the U.S. and a victory for the Communists. It also would encourage the Communists and leftist elements in other parts of Africa to adopt the same tactics they have been following in Ghana. The Soviet bloc desires us to leave Ghana and is actively engaged in promoting this end.”

The US cited the chances of the Soviet Union aligning with Ghana as a reason for the proposed coup, even though Nkrumah consistently pursed a policy of non-alignment, which was expressed in his famous saying: “We face neither East nor West: we face forward.”

Trimble stated: “Nkrumah is convinced that the U.S. is the principal obstacle to his program for African unity. He is also convinced that through the CIA we are seeking to engineer his downfall.”

Nkrumah, meanwhile, believed that if African states failed to unite the imperialist powers would instigate further conflicts on the continent. In a 1958 speech during the All-African People’s Congress, he called on African leaders to “not let the colonial powers divide Africans, for the division of the African continent is their gain.”

In ‘Africa Must Unite’ (1963), he warned:

“To ensure their continuous hegemony over this continent, they will use every and any device to halt and disrupt the growing will among the vast masses of African population for unity. Just as our strength lies in a unified policy, the strength of the imperialist lies in disunity.”

Covert operations of the British press

In the 1960s, the Information Research Department (IRD), a covert propaganda unit of the UK’s Foreign Office, carried out a campaign to undermine Nkrumah, including allegedly publishing several articles in the African Review, a publication secretly run by the IRD, in which they described Nkrumah’s Africa unity efforts as an attempt to rule Africa under Soviet influence.

These publications were often made under fictitious names and groups or in some cases were unattributable, which British diplomat John Ure, who worked with the IRD, described in a report in 1966: “The African, Editorial and Special Operations Sections of IRD have, throughout, worked in very close liaison over our treatment of Nkrumah’s Ghana; this treatment aimed at contributing to the creation of an atmosphere in which Nkrumah could be overthrown and replaced with a more Western-Oriented government.”

Most Ghanaians lived in rural areas at the time, and Nkrumah enjoyed significant popularity among them. However, this cohort was not the target of the IRD’s efforts. It was seeking to tarnish Nkrumah among the middle class and the urban intellectuals.

“Ghana has no apologies to render to anybody”

The UGCC had increasingly adopted colonial ideology favoring divisions championed by Britain, which opposed the unity envisaged by Nkrumah. To promote unity in line with Ghana’s foreign policy, the country’s parliament passed with Nkrumah’s support the Preventive Detention Act to prosecute those who attempted to destabilize the government. The British capitalized on this controversial piece of legislation to label Nkrumah a dictator.

In 1963, antagonism rose against Nkrumah by leaders who preferred an approach towards African liberation that was more conciliatory toward the former colonial powers. Notable examples were Sylvanus Olympio of Togo and Felix Houphouet-Boigny of Ivory Coast, who maintained closer ties with France. This antagonism grew to include accusations of a plot against Houphouet-Boigny and subsequent murder of Olympio. The colonialists were quick to blame Nkrumah for these occurrences, though Olympio was assassinated by members of his own army, many of whom had served in the French colonial force.

Nkrumah responded to the series of accusations unapologetically:

“There are many people who attribute the recent disturbances in Nyaasland in the Congo and in colonial territories of Africa directly to the deliberations which took place at the All-African People’s Conference. Such people believe Ghana has become a focal point for all of the anti-imperialist, anti-colonial forces and political agitations for Independence in Africa. On our part, we say these accusations are the greatest tributes that the enemies of Africa’s freedom could pay to Ghana and Ghana has no apologies to render to anybody nor has any excuses to make.”

Coup and legacy

Meanwhile, dark clouds were gathering over Nkrumah, who had already survived several assassination attempts and was being increasingly accused of employed strong-arm methods.

While visiting Hanoi in February 1966, where he was mediating Vietnam War talks, Nkrumah was overthrown in a plot led by the CIA-backed National Liberation Council, a military junta headed up by elements of the Ghanaian military, many of whom had been educated at British military academies. It was a coup very much aided by the CIA, as numerous sources have demonstrated.

John Stockwell, former chief of the Angola Task Force who later criticized the CIA, wrote that agents at the agency’s Accra station “maintained intimate contact with the plotters as a coup was hatched.” Later that same year, Seymour Hersh supported Stockwell’s account, citing “first hand intelligence sources.”

In a book called ‘Dark Days in Ghana’ written two years after the coup, an exiled Nkrumah explained that: “It has been one of the tasks of the CIA and other similar organizations to discover… potential quislings and traitors in our midst, and to encourage them, by bribery and the promise of political power, to destroy the constitutional government of their countries.”

Meanwhile, shortly after the coup Ure wrote a report with a chilling and quite telling conclusion: “Now … our efforts are being directed at ensuring that the lesson of Nkrumah’s flirtation with Communism is not lost on other Africans.”

After the coup Nkrumah, who ended up receiving an honorary doctorate from the Moscow State University and the USSR Academy of Sciences, went into exile in Guinea. He would end up dying of cancer on April 27, 1972.

Nkrumah had long been disparaged in Western sources as a dictator who badly mismanaged his country’s economy while engaging in human rights abuses. And yet the pro-Western National Liberation Council that succeeded him was far worse on both fronts. Furthermore, it embarked on a policy of privatization that facilitated the return of Western control over much of Ghana’s economy.

Whatever his shortcomings may have been, Nkrumah was a towering visionary, whose tireless efforts at African unity and freedom were never fully achieved, but have remained a beacon of light for subsequent generations. His insight into the true nature of neo-colonialism was ahead of his time and is still relevant today. That he was looked upon so warily in Washington and London is a testament to the scope of his influence.