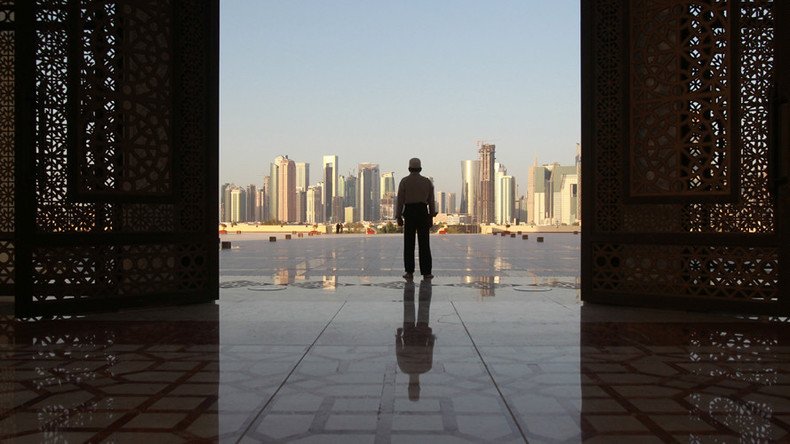

Qatar blockade could cause a regional recession

Five months into the Gulf’s blockade against Qatar, and neither side looks ready to budge. But the repercussions of the ongoing spat—and Kuwait’s failure to end the dispute—could deliver a huge blow to the Gulf economy.

Doha has stood its ground: It refuses to shut down its renowned news station Al Jazeera or abide by the sectarian politics orchestrated by Riyadh. Saudi Arabia and its allies (the United Arab Emirates, Bahrain, Egypt and others) maintain that Qatar’s relationship with Iran and other Shi’ite regimes contributes to disharmony in the Middle East.

A series of ultimatums, diplomatic talks, and regional sanctions have yielded no results. Kuwait volunteered to mediate between the sparring parties a couple of months ago, but despite international encouragement for its leadership, the country has made no progress in resolving the impasse, which could lead to a regional economic recession if not remedied soon.

In 1982, the collapse of Kuwait’s Souk al-Manakh, the nation’s stock exchange established after the discovery and production of oil in the small emirate, demonstrated how the collapse of one Gulf state can quickly affect its neighbors.

The Souk al-Manakh started in 1981, just as oil profits began rolling into the bank accounts of Kuwait’s biggest fossil fuel investor. Soon after, lack of government oversight paired with uncontrolled speculation caused a market crash that created $94 billion in debt—a figure that totaled over four times the value of Kuwait’s national GDP at the time.

Bahrain and the UAE developed special committees to determine the scope of economic damage they suffered as a result of Kuwait’s malfeasance. The collapse of the “camel market,” as it was known colloquially, drained foreign capital from the Gulf and noticeably discouraged new foreign investment for at least a few years.

Qatar's wealth enough to outlast boycott by Arab neighbors - Central Bank https://t.co/r4M1j7trFA

— RT (@RT_com) July 10, 2017

Qatar was immune from Kuwait’s first dalliance with Souk al-Manakh because the nation didn’t set up its first trading center until 1997. The oil price drop of the 1980s, which followed soon after the Kuwaiti market crash, did concern Doha, however. Regulators tightened their grip and cut infrastructure spending to keep budgets balanced without having to cut welfare spending.

Kuwait is now preparing to launch its “grown-up” stock market sometime next year, just as Saudi Arabia prepares for its state-run oil company to undergo an initial public offering. The Gulf’s financial sector is undergoing major changes, and Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman’s tough anti-Iran stance is adding fuel to a centuries-old, fiery clash of civilizations between Persia and Arabia.

For Qatar and Iran, the relationship is one of necessity. The two nations share a stake in the South Pars gas field, which is the largest reservoir of its kind in the world. Doha’s resilience in producing and delivering liquefied natural gas to its customers via an Omani port demonstrates the country’s independence and resolve to keep its politics non-partisan. But the continued excision of Qataris and their wealth from the rest of the Gulf nations will begin affecting regional development in due course.

Saudi Arabia is on course with a Saudization policy that aims to reduce its reliance on immigrant labor in the public and private sector. In a sense, the banishment of Qatari workers from Riyadh and other economic centers speeds up this process, but at an unnatural rate. Forcing companies or government agencies to turn over jobs held by Qataris to other workers in 14 days isn’t likely to lead to positive outcomes in the short and medium terms.

The latest on the Gulf row has Kuwaiti Emir Sheikh Sabah al-Ahmad al-Sabah concerned about the future of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC), the main organization that binds the region.

"An escalation would be an explicit invitation for regional and international intervention, which would have serious consequences for the security of the Gulf nations and their people," the emir said. "History and future generations will not forgive anyone who contributes, even one word, to fueling this dispute."

The economic consequences won’t be forgiving for the region, either.

This article was originally published on Oilprice.com