Despite the economic interests of both countries, the political disagreements between China and Australia have escalated in recent years, and tensions are now beginning to reach a boiling point.

The Chinese economic engine requires vast quantities of raw materials such as coal to power industries. While the majority of the coal is mined domestically, China is increasingly dependent on imports to satisfy its needs. Australia, in comparison, is an important exporter of several raw materials which has benefited from the expanding South-east Asian economy in general and China's in particular. However, relations between Canberra and Beijing have deteriorated significantly over the years and reached rock-bottom which is a major threat to the Australian mining industry. The economies of the two countries are highly complementary. China requires vast quantities of raw materials such as iron ore, natural gas, and coal which Australia has in abundance. Furthermore, low production costs and relative closeness to Asian markets are important assets. The Australian mining industry is strongly dependent on Chinese imports.

Therefore, the bellicose language of the current leadership in Canberra came as a surprise to Beijing. Political relations started to deteriorate after Huawei was effectively banned in August 2018. Canberra's call for an international investigation into the origin of the coronavirus was the last straw for China. Since then, Beijing has increased pressure on Australia to make an example for others.

Step by step tariffs are levied on a growing list of products such as barley, beef, and wine, to name some. Australia's mining and energy sectors are the biggest export earners with a third of the revenue in 2019. The largest customers for these products are Chinese companies. Therefore, Beijing's policy shift when it comes to Australian imports is a warning for the coming difficult period. Especially sectors that can relatively easily be substituted risk being affected such as the mining industry and coal.

A string of accidents and tougher environmental rules in China have made ramping up the production of coal difficult. Therefore, it is likely that consumers will remain partly dependent on imports.

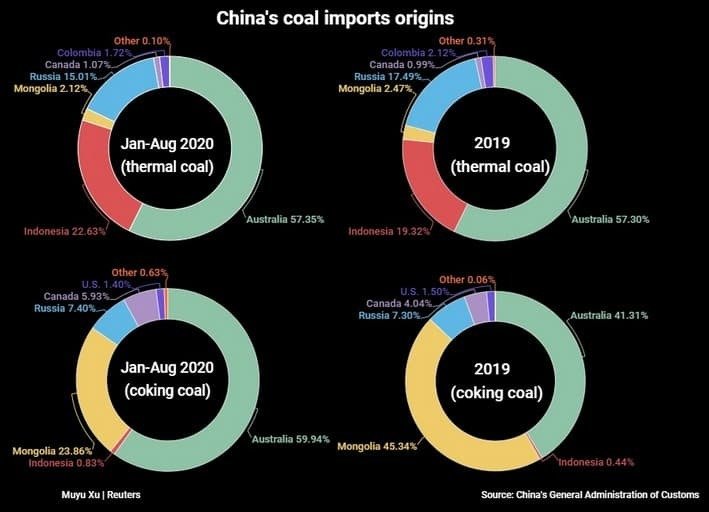

These can be divided into two types: thermal and coking coal. The former is used in power plants and the latter in the production of steel. Last year miners in Australia supplied 40 percent of the total coking imports and 57 percent of the thermal coal. It will be less in 2020 and a major decrease is on the horizon for next year also.

Beijing introduced a quota system several years ago to support its domestic mining industry. Until year's end, an additional 20 million tonnes is allowed into the country. Primarily Indonesia and Russia will benefit while Australian producers are likely to feel the brunt of Beijing's ire. According to the Guardian, 60 bulk carriers holding Australian coal are already stranded off the Chinese coast for between 4 and 24 weeks.

Australia's strained relations with its most important customer couldn't have come at a worse moment. The country's economy has benefited handsomely over the past decades which recorded 28 consecutive years of growth. Even after the financial crisis of 2008 Australia's economy wasn't affected significantly such as the rest of the world due to China's building spree and insatiable demand for fossil fuels and iron ore. The Covid-19 pandemic, however, has brought to an end an unprecedented period in the country's economic history.

Also on rt.com Beijing slaps up to 212% tariffs on Australian wine in response to price-dumpingCanberra's acknowledgment of the necessity to reduce tensions can be seen in its attempts to start a dialogue with China. Australia's trade minister has reached out to his counterpart in Beijing, but apparently, no one is picking up the phone or calling back. The strong language from Canberra came at an especially sensitive moment as relations with the U.S. were worsening. Beijing interpreted the criticism as Australia doing President Trump’s bidding.

This caught the Chinese off-guard, but also presented an opportunity. From Beijing’s point of view their economic relations with Australia are unbalanced in their favor. While many products are imported from the island state, most can be easily replaced by products from other destinations. Australia, therefore, is far more dependent on China than the other way around. The opportunity has presented itself to make an example for others meaning trade relations come with a string attached: don’t interfere with internal matters.

This article was originally published on Oilprice.com