Abuse only gets worse with time: How the US increasingly mistreats its closest allies

At a recent investment forum in Moscow, Russian President Vladimir Putin remarked on the ill-treatment the US subjects others to. At first glance, this is hardly news. Washington has an extensive toolkit that includes all types of sanctions, economic coercion, and regime-change operations to deal with its real or perceived adversaries. But in this case, Putin was commenting on Washington's treatment of its very own allies.

“In fact, the US… exploited its allies just like any other actor of the global economy,” the Russian president said.

Recent events have laid bare a strategy that has been central to US policy for decades, and now the world is increasingly taking notice.

The early seeds of exploitation

Now, the advantage is ours here, and I personally think we should take it.”

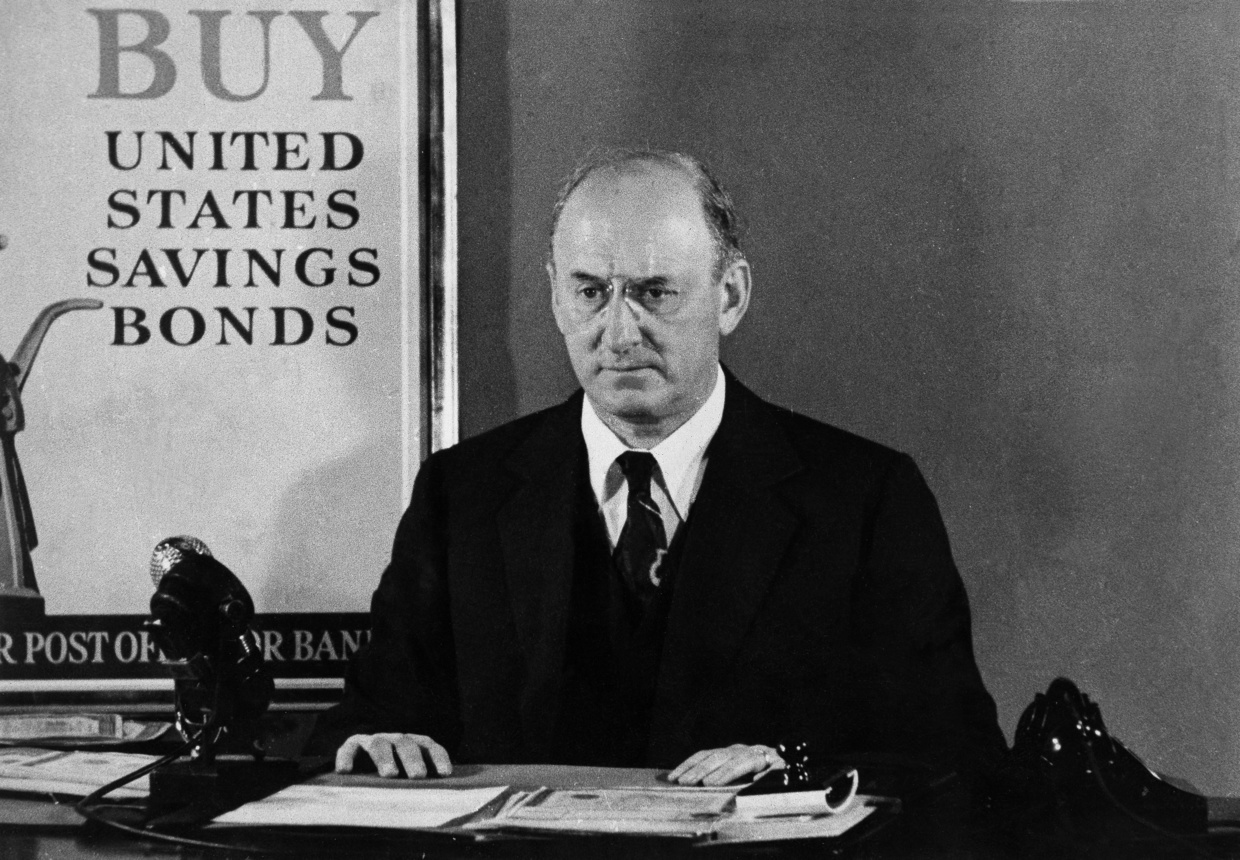

It is July 1944, and these are the words of US Treasury Secretary Henry Morgenthau. World War II had turned decisively in the Allies’ favor, and delegates from 44 countries had convened in the New Hampshire resort town of Bretton Woods to hash out a post-war economic order.

Morgenthau was instructing the American delegation to the conference, which was led by Harry Dexter White, a senior Treasury official. White fully agreed with his boss, replying: “If the advantage was theirs, they would take it.”

If the Americans clearly did hold the advantage, one might wonder which American adversary White had in mind in his reply: Who was the “theirs?” The Axis powers, presumably? No. He meant Great Britain, a close ally whose troops had stormed the beaches of Normandy side-by-side with the Americans just a few short weeks earlier – but by this time was in dire economic straits and nearly bankrupt.

It is rare to see the American approach articulated so clearly and unabashedly. Since even before World War II ended, a central feature of US policy has been to bring allies into its economic orbit – not as equals, of course, but as dependencies – and to keep them there.

If, in the initial postwar period, there was at least some legitimate benefit to adopting US-centric trade and monetary policies, as the US economy has become an increasingly indebted and financialized shell of its former self, Washington has had little to offer allies except threats and coercion.

However, maintaining discipline through a whole lot of stick and not much carrot can’t work forever, especially as a new, multipolar world forms that promises opportunities for new partnerships. The US risks, as historian Michael Hudson put it, suffering the fate of the protagonist of a Greek tragedy, who brings about precisely the outcome that he had sought to avoid.

Multilateral collaboration – the American way

Bretton Woods has long occupied a cherished place in the creation myth of the American-led ‘rules-based order’ as a shining example of collaboration among enlightened states to usher in a prosperous new world and avoid the mistakes of the [1919-1939] interwar period that gave rise to economic nationalism and protectionism – policies seen as helping the nascent Nazi regime germinate.

But the US saw the conference and the initial post-war era as a geopolitical struggle and an opportunity to dismantle the fading British Empire and roll out a new economic system that would cement the primacy of the dollar and spawn institutions such as the IMF and World Bank, which would serve American interests.

In fact, economist Benn Steil, author of the book ‘Battle For Bretton Woods,’ argues convincingly that even as the war was ongoing, the Roosevelt administration was already examining how it could turn Britain’s impending bankruptcy to its geopolitical benefit. The US, Steil maintains, was managing its financial aid to Britain carefully to get it through the war but, at the same time, limiting its room for maneuver in the postwar world. Incidentally, the US providing an ally with just enough aid to muddle through a war while turning it into a client state might ring familiar to observers of the current conflict in Ukraine.

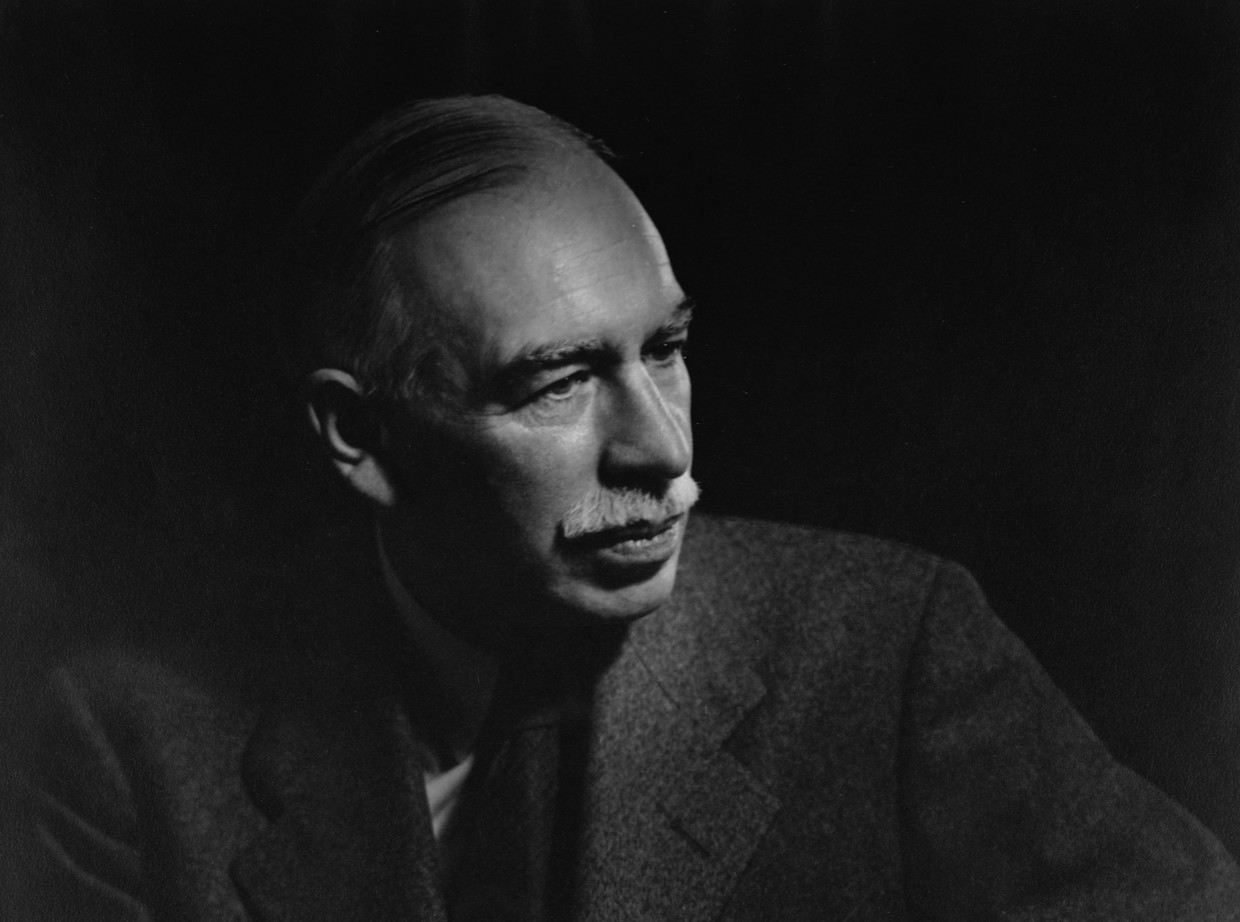

Meanwhile, at Bretton Woods, the Americans made good on Morgenthau’s exhortation to press their advantage. They pushed through their proposal for the dollar to be pegged to gold at $35/oz and all other currencies pegged to the dollar over the British proposal, as articulated by the renowned economist John Maynard Keynes, for the creation of a neutral reserve asset called bancor that would be used to settle trade between nations.

Geoffrey Crowther, then the editor of The Economist magazine, called the bancor proposal a much better idea and warned that “Lord Keynes was right ... the world will bitterly regret the fact that his arguments were rejected.” As the US increasingly abuses the privilege the dollar grants it while the BRICS group seeks to create a neutral supranational currency that will, in some key ways, resemble the discarded bancor, Crowther seems prophetic.

What had gotten Britain through the war was the Lend-Lease program launched by the US in 1941, which provided London with crucial financial aid. But, much to the surprise of the British, the program was abruptly stopped when the war ended. By late 1945, the country’s economy was in tatters.

British Prime Minister Clement Attlee dispatched an ailing Keynes – less than a year from death – to Washington seeking financial assistance. The eminent economist and his countrymen were expecting a generous offer from the Americans – grant aid or an interest-free loan – in recognition of the tremendous sacrifices of the British war effort, which predated the US becoming involved.

Keynes would be in for a rude awakening. Far from receiving a subsidy as a show of gratitude, what was offered after months of hard wrangling – called the Anglo-American Loan Agreement – was a very commercially oriented $4.4 billion loan laden with terms that essentially economically subjugated Britain to its former colony. It was in those onerous conditions that the true demonstration of American superiority lay.

First of all, the Brits had to liberalize trade and open up the Commonwealth to US exporters, who proceeded to displace British companies. But even more devastating was the stipulation that the pound be made convertible to the dollar at a fixed rate. This would allow Britain’s colonies and dominions to unload sterling for dollars, a longstanding demand of US exporters, but it would also further drain London’s already meager reserves.

Indeed, in July 1947, when the measure took effect, the pound succumbed to overwhelming selling pressure as capital flowed out, and the UK essentially went bankrupt. Shortly thereafter, the free convertibility of the currency was suspended. It was an event entirely scripted by the US Treasury.

The loan agreement was, to put it mildly, not well received in the UK. MP Robert Boothby called it “our economic Munich.” Labor MP Norman Smith complained that the country was being treated as the defeated party in the war.

British politician Leopold Amery argued that the convertibility clause caused the country to lose control of its own currency, which furthered American control over Britain’s monetary policy.

However, fearing the alternative to accepting the loan was worse, Attlee and the Labor government relented and agreed.

Great Britain eventually recovered economically and paid off the loan, making the final payment in 2006 to some fanfare, and the circumstances surrounding the agreement were largely forgotten in the UK. But what is incontrovertible is that from this point on Britain would be firmly entrenched in the dollar system and entirely in the US orbit.

Ushering in Japan’s lost decade

If Great Britain was an empire already in terminal decline whose departure from the stage of superpowers was only hastened by Washington, Japan was quite the opposite. Having recovered remarkably quickly from the destruction of World War II, by the late 1970s, it had established itself as the world’s second-largest economy and had emerged as an innovation and technology hub every bit the equal of the US. It had also become a staunch ally of Washington during the Cold War.

The US, meanwhile, had just emerged from a recession and a long bout of inflation only quelled by the draconian efforts of Fed Chair Paul Volcker. Ronald Reagan was in office, and it was full-steam ahead with a set of policies – tax cuts on the rich in tandem with interest rate cuts – that would lead to skyrocketing budget deficits and a massive increase in foreign debt.

Japan, meanwhile, was running huge trade surpluses as a result of selling the world everything from cars to video cameras. As Reagan ran up huge deficits – in no small part to boost military spending in an effort to drive the Soviet Union to bankruptcy while trying to keep up – Japan plowed huge sums into US Treasuries, thus helping to finance the deficit spending.

It was certainly a fantastically convenient arrangement for the US and one that by no means emerged by chance. One of the great achievements – if you want to call it that – of the US-engineered financial system is that it managed to make its own debt an indispensable part of the undergirding of the entire system.

To look at this in a larger context, when Great Britain was the world’s largest debtor and the US the largest creditor at the end of World War II, this state of affairs was seen as an insurmountable weakness on the part of the British that rendered them entirely beholden to their creditor. But when the US assumed that exact same role as the world’s largest debtor – with Japan and subsequently China in the role of largest creditor – there was no sense that it put the US in a position of fealty. That is because the US was issuing its debt in its own currency and had managed to leverage its economic and military strength to ensure the global prominence of that currency.

For the Japanese at the time, though, it’s hard to imagine what else they could have done with the huge surplus balances they were accumulating. The US was just about the only game in town.

But with pro-growth policies running on all cylinders in the US, Washington began to see the dollar as overvalued. In September 1985, the G5 delegates met at the Plaza Hotel in New York and reached an agreement at the behest of the US whereby the main current account surplus countries – Japan and Germany – would strengthen their currencies, ostensibly to boost domestic demand.

The result was a sudden appreciation in the Japanese yen – it was up 46% against the US dollar by the end of 1986. Accordingly, Japanese exports essentially collapsed, having been made too expensive. In order to compensate for this, the Japanese authorities introduced a number of stimulus measures that essentially created a bubble in the economy – most notably in the real estate sector.

What ensued, albeit not immediately, was Japan’s so-called ‘Lost Decade,’ the direct cause of which was interest-rate hikes by the Bank of Japan to cool down the overheated real estate market. However, the overheating was a direct consequence of the measures taken to soften the blow of the US-initiated Plaza Accord. As Michael Hudson points out, what essentially happened was that it was actually the US that triggered the bubble in the first place – via cutting rates and increasing spending. But through the Plaza Accord, it managed to export the consequences of that bubble to its allies – namely Japan.

There is another angle to the US assault on its ally Japan’s economy. By the 1980s, the Japanese were at the absolute cutting edge in innovation. This resulted in a clash with the US over something that would sound familiar to contemporary observers: the semiconductor trade. Japanese firms had begun to produce chips of arguably higher quality than the American ones but at a significantly lower cost.

This, of course, did not sit well with the Americans, who feared that Japan might not only gain the upper hand economically but also militarily, since advanced technology was a cornerstone of US military dominance.

None too pleased with the rise of an ally, the Reagan administration took action. In 1986, the US pressured the Japanese into agreeing to set a price floor for chips sold abroad and promising that its companies would buy more chips from the US. Dissatisfied with Japan’s tepid compliance with these conditions, the following year the US went further and imposed 100% tariffs on a range of Japanese goods, including computers, televisions, and a number of hand tools.

It was the most stringent economic measures taken against Japan since World War II and, coming on top of the Plaza Accord, played no small role in Japan’s economic decline from which the country has still not fully emerged to this day.

A bigger stick and a much-diminished carrot

However manipulative US policy towards its allies was in the early postwar period, there is no doubt that being economically aligned with the US – while certainly doing nothing for national sovereignty – did provide benefits, sometimes even considerable ones.

The US emerged from World War II with roughly three-quarters of the world’s monetary gold stock and was responsible for around 50% of GDP. It was by far the globe’s leading industrial power and was able to disburse aid and provide the manufacturing and financial muscle to rebuild war-torn economies. It is hard to argue that the Marshall Plan didn’t help a devastated Germany get back on its feet – even if it did cement Germany as an ally that, as we have learned recently, is willing to severely compromise its own interests for the sake of US policy aims.

Even the dollar system, as self-serving for the US as it has been, did serve the purpose of providing liquidity and ease of trade in a rapidly globalizing postwar world. Many economists argue that such rapid growth in international trade would have been unfeasible under any sort of gold-based system. There were complaints about the primacy of the dollar as far back as the 1960s, especially from the French, but it is telling that until recently there were no real steps taken to fundamentally change the system.

Of course, there were instances of egregious abuse by the US – such as when President Richard Nixon unilaterally pulled the US out of Bretton Woods by removing the gold backing to the dollar in 1974 without even so much as consulting with allies.

But there was also some attempt to acknowledge the responsibility for managing the global currency in the best interests of everybody. When Volcker traveled to Belgrade for the IMF meeting in early October 1979, the dollar was in the midst of a full-blown crisis due to rampant US inflation. In Belgrade, he met with key American creditors, namely the German and French, who, by all accounts, told him sternly that he must do something to stem the dollar weakness that was eroding the value of their holdings with each passing day.

Volcker spent less than 24 hours in Belgrade and did not even stick around until the end of the conference. He departed back for Washington, by the Fed’s own account, with his ears ringing from the admonishments of America’s trading partners.

Just days later, he unveiled a set of measures, dubbed the October Reform, aimed at reining in inflation – and, by extension, protecting the dollar and the value of the holdings of American trade partners.

But what has transpired since has been a steady hollowing-out and financialization of the US economy – meaning an increase in leverage on a decreasing sliver of actual economic activity. America’s industry was largely offshored and replaced with a growth model based on inflating real estate and securities prices, boosting corporate profits through offshoring production and endless stock buybacks, and taking advantage of the fact that the US could still raise almost endless debt in dollars without suffering the usual consequences.

The US is rapidly losing its billing as the only game in town and, in its current state, has very little to offer allies. It is not difficult to see that the likes of China, Russia, and many others can now offer superior trade and investment opportunities. And now Washington is well on its way to debauching the value of the only thing keeping it afloat – the dollar – not only by weaponizing it but also through unprecedented fiscal profligacy.

Bringing the story up to the present day, when the US was pressuring Germany to abandon the Nord Stream 2 pipeline project with Russia, even before the conflict in Ukraine began, it was almost a crude parody of the sophisticated paternalism previously practiced by the US. Not only was it an utterly brazen attempt to interfere with an ally’s own affairs – as if the Germans themselves couldn’t weigh the risks of doing business with Russia – but it so blatantly contradicted Berlin’s own interests that it can’t be seen as anything other than an act of desperation.

So, when US President Donald Trump stood side-by-side with Russian President Vladimir Putin at their press conference in Helsinki in July 2018 and announced with his usual bluster that the US was planning on “competing” for the European gas market, it was a mix of disingenuousness and fantasy thinking – disingenuous because the US had no intention to compete on a level playing field and fantastical because the US, with its LNG priced some 30-40% above Russian piped gas, couldn’t compete anyway.

The US did end up displacing Russian gas in Europe, but hardly because it ‘outcompeted’ Moscow. The wreckage of the Nord Stream pipeline at the bottom of the Baltic Sea is not a display of American strength.

The Nord Stream episode, the sanctions on Russia, the attempts to coerce Europe to decouple from China – these can be thought of not so much as attempts to keep Russia and China ‘out’ but to keep the allies ‘in.’ A new Iron Curtain is descending, not on the opposing bloc but on America’s own allies, who are to be perpetually locked inside an increasingly desiccated system.