Goldman Fraud explained

Goldman Sachs is charged with fraud, for assembling and selling a financial product that it knew to be flawed. A product which, in fact, it intended to be flawed, so that it could bet against it.

Subprime mortgages triggered the global financial crisis. Now regulators from the US Securities and Exchange Commission say they’ve identified that Goldman Sachs deliberately sold packages of low quality mortgages to customers and then bet against them. As the subprime mortgage market collapsed, as millions of people lost their homes, Goldman got rich.

The news has shocked the global markets even though the only real surprise is how long Goldman Sachs managed to deceive the regulators.

You read it here first. Long before fashionable articles described Goldman Sachs as a vampire squid wrapped around the face of humanity, we focused on the central role of Goldman in this crisis.

The role of Goldman Sachs’ former boss in rewriting regulations so that banks could take on more risk in the years directly before the crisis exploded in autumn 2008.

The role of the same man, Henry Paulson, as US Treasury Secretary, in promoting the lie that all civilisation would collapse unless taxpayers were forced to pay off the banks’ bad bets.

We remarked on the ease with which Goldman Sachs had sold off its subprime mortgage assets and actually profited from the scandal, before managing to milk millions from western governments.

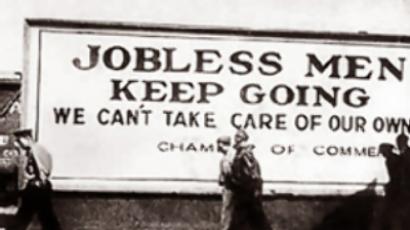

We highlighted that Goldman Sachs had done it all before. Back in 1927 and 1928, just before the Great Crash of Wall Street, Goldman Sachs was marketing investment funds that ripped off investors while making the investment bank very, very rich.

So how did Goldman get caught this time?

The first thing you have to know is Goldman Sachs is a trader. Information is money. However, it also conducts trades for other institutions and sells financial products and manages money for clients.

There is a fine line between betting against your clients and taking a contrary trading position when you know your clients’ trading positions intimately because you are their bank.

Goldman Sachs calls this knowledge “market colour” and denies that it constitutes insider trading which is illegal in the United States.

In October 2009 investment company Galleon and its founder Raj Rajaratnam were accused of insider trading amid reports that it paid hundreds of millions of dollars a year to investment banks for information that is withheld from general investors. Goldman Sachs stated at the time: "Any suggestion that we provided inside information to Galleon is completely untrue."

Only a clueless innocent thinks banks set up investment products purely to benefit the customer or that, when there is a performance element in which you have to beat some benchmark, that you have an equal chance.

It’s not the financial markets that are rigged, but the banks that operate like casinos, luring in the punters with promises of riches and fair play, while always stacking the cards against the customer. It’s how the market in financial products works.

Goldman admits this. As part of its defence it says that its clients were experienced market players. “The risk associated with the securities was known to these investors, who were among the most sophisticated mortgage investors in the world.”

We already knew that Goldman bet against its own clients so why did the US market regulator charge Goldman now?

Not content with trading against its clients, the US Securities and Exchange Commission suggests Goldman designed products and sold them to customers, specifically so that Goldman and selected clients could bet against them. Furthermore, the SEC suggests these products were specially selected to be a good bet for Goldman and a bad bet for the customers who bought them.

But why are the US authorities charging Goldman Sachs with fraud only now?

When the markets tumbled in Autumn 2008, Goldman Sachs received a back-door bailout from the US government. It had insured collateralised debt obligations (a form of insurance against default by any product, including subprime mortgages) with the world’s biggest insurer, American Insurance Group. As AIG stumbled towards bankruptcy, the government gave AIG the money to fully compensate Goldman Sachs, not just for the cost of the insurance but for the full sum insured.

This was at a time when the banks were insisting their fancy financial constructions like CDOs were still worth money. You might wonder why Goldman needed to be paid the full sum insured when it still owned the object insured.

It was a bit like an insurer paying the dealer the full value for a car that’s still standing on the forecourt.

Except that Goldman Sachs (imagine for a moment that it’s the car dealer) was selling a lemon. It was trying to sell to the public a car, constructed from pieces of other cars, that wasn’t roadworthy, while placing a bet that the car wouldn’t make it to the end of the road in one piece.

In its defence, Goldman says it was not offering the car to the public but to sophisticated investors, and that it didn’t claim insurance for this particular car but for others like it.

The integrity of US regulators, not just of Goldman Sachs, is on trial.

Mark Gay, RT Business