Great Depression v2.0?

The real economy is in peril. European governments have put huge chunks of state cash into their top banks to shore them up and have cut interest rates to help companies and consumers. How bad are things?

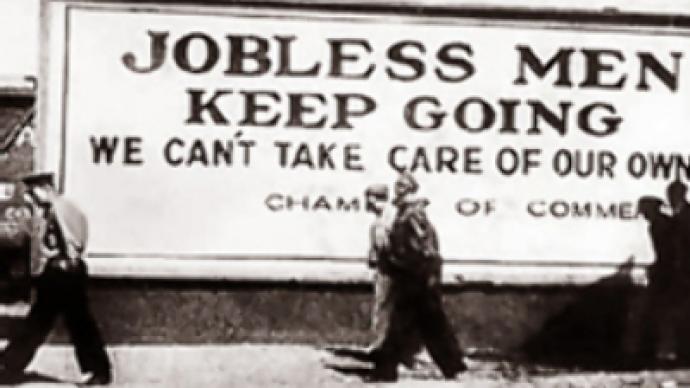

Are we really looking at a repeat of 1929 and the Great Depression that followed?

First, the differences.

1928 and the year that followed saw a huge stock market boom, much bigger than anything we've had since. The speed and size of gains sucked investment from the rest of the U.S. economy.

Nowadays, we have seen a long bull market but higher productivity may justify share prices. However, we have had other asset booms, notably in real estate.

Other countries were weakened by the First World War. Many were in debt to the U.S. The U.S. government's response to the 1929 crash – restricting imports – was to hammer those debtors and push other exporting nations into depression.

Nowadays, the U.S. is a debtor nation. It borrows from other countries and dare not let the value of the dollar fall. It is likely to avoid trade restrictions.

Now the similarities with 1929. They are bigger than you think.

In late 1920s America, the real economy looked fine. For the first time, middle class Americans could expect to live a bit like the rich. Consumers were buying cars and fitting out their homes, not just buying the basic foodstuffs of survival.

But the asset boom (stock markets in 1928-29, real estate and mortgage-backed securities today) sucked investment from the rest of the economy.

Investment banks dreamt up financial products which promised to make the man in the street rich beyond his dreams – using borrowed money. Companies bought up their rivals – using borrowed money.

Banks created all these loans by borrowing against securities (shares, bonds, mortgages). Nothing wrong with that, except that many of these securities had themselves been purchased on margin, i.e., with borrowed money.

Sound familiar?

The banks call this leverage – borrowing money to buy shares or other securities and then re-lending them.

In 1928 Goldman Sachs and the now collapsed Lehman were both launched on the back of new-fangled investment trusts, using loans to multiply the capital gain from rising stock prices. Then they created further investment trusts which invested in the existing investment trusts.

Eighty years later, both Goldman and Lehman were at it again, using the same basic technique, this time magnifying the gains from securities (shares, bonds, mortgages).

Unfortunately, this leverage works both ways. In 1929, a small fall in share prices led to a much bigger fall in the value of the investment trusts. This soon gathered pace, wiping out first the small investors, then some stockbrokers and then the banks.

History may show Goldman Sachs to have been more careful in the 1920s. The promoters of investment trusts took their profits early, leaving the later investors to bear the losses.

In 2008, the investment banks were among the first to seek government protection.

But the investment schemes they sold are now dragging down the commercial banks, the local government treasuries and the insurance companies – as well as pension funds, the money market funds and mutual funds in which ordinary people stored their savings.

How will it affect the real economy?

All companies, like individuals, need loans at some time. However, investment bank lending is not about these kinds of loans.

The investment bank frenzy has led, as in the late twenties, to entire holding companies being constructed on a mountain of debt. Investment banks call it mergers and acquisitions.

Thus productive companies are bought up by holding companies, which use the earnings of the productive companies to pay that debt.

As the leverage goes into reverse, the holding companies cut investment in machinery and wages because they need to pay back their debt.

When banks and companies de-leverage, it can rapidly stifle economic growth.

There is a saying that economies cause recessions, governments cause depressions.

Governments cannot stop asset prices falling. What they can do is not make the situation worse. They must keep taxes low, cut barriers to trade, buy and sell to other countries, invest in their own infrastructure, help the unavoidable unemployed.

Mark Gay, RT