Go for broke: Ukraine’s risky EU trade deal

Tough admission standards could keep Ukraine’s trade integration with the European Union on hold, and if the process is dragged out long enough, it may be forced back into the arms of its ex-Soviet ally, Russia.

European Union ministers will meet on November 18 ahead of the

Vilnius summit and decide if Kiev has met enough criteria to sign

the dotted line on its trade association agreement.

The Ukrainian government approved their draft resolution on

September 18 and the agreement will either get a ‘yes’ or ‘no’ at

the Eastern Partnership Summit in Lithuania on November 28-29.

If European Union officials reject Ukraine from their trade

association, Kiev will need to reconsider Moscow's proposal to

join the Russia-led Eurasian Customs Union.

Russian President Vladimir Putin has tirelessly tried to convince Ukraine to join Russia, Belarus, Kazakhstan, and other former Soviet nations in a trade bloc that will rival the EU.

Russia, Ukraine’s main source of energy, loans, and trade, wants to dissuade its geographical partner from making a ‘suicidal’ move towards Europe and sacrifice the option of joining Putin’s customs union.

Ukraine, resource-rich and in need of a serious IMF loan, sees more economic opportunity in Europe, and hopes to act as a ‘bridge’ between Russia and the EU, President Viktor Yanukovich, 61, has said.

Russia has made it clear there will be no ‘bridge’ if Ukraine steps West; they will give up their ‘exclusive relationship’ with Russia, Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev said on Friday.

“Uncertainty remains as to whether or not Ukraine will sign an association agreement with the EU,” Standard & Poor’s rating agency said in a November 1 credit report that downgraded the country’s long-term sovereign credit rating to B-, the same junk level as Greece.

Caught between two stools

Ukraine is facing its most important economic crossroads since the collapse of the Soviet Union. It is caught between two stools - it wants to move towards integration with the west, but doing so is irritating Russia, which imports nearly 25 percent of Ukraine’s export goods.

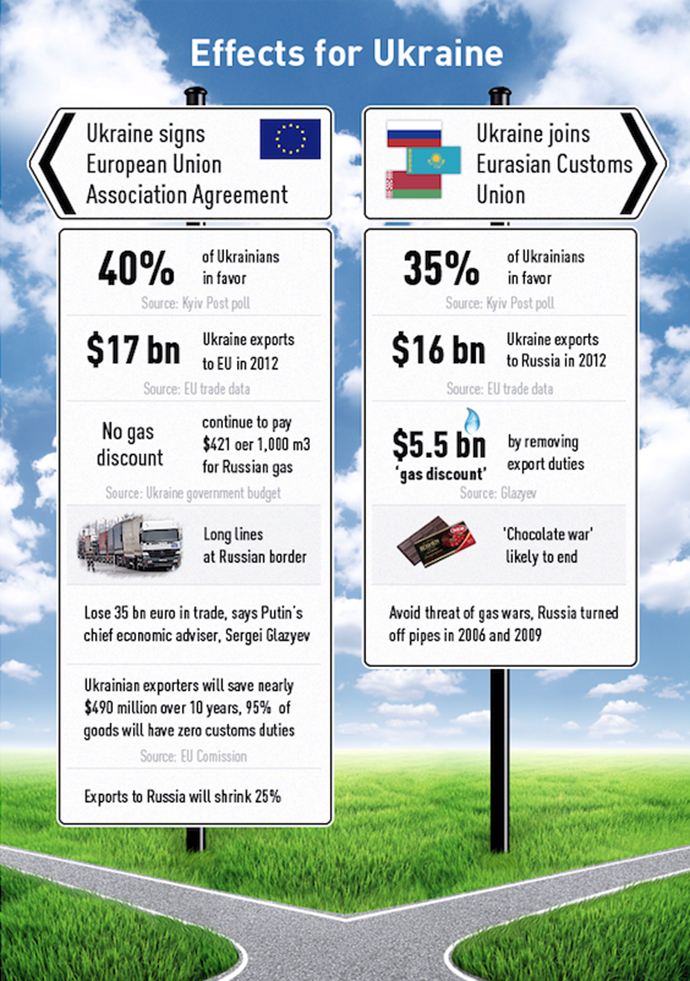

Ukrainian exporters will save nearly $490 million over 10 years,

as 95 percent of goods will have zero customs duties, according

to the European Commission.

Russia claims Ukraine’s choice to team up with Europe will come at a cost of 35 billion euros worth of Ukrainian goods. This will force it to default on its sovereign debt, of which Russia owns a great portion.

Ukraine, Europe’s second largest country by land mass, a nation

of 45 million people, has a gross domestic product of $176

billion, less than 10 percent of Russia’s $2 trillion GDP.

Ukraine’s depreciating currency reserves and massive deficit prompted Moody’s rating agency to cut its Caa1 rating to Caa1 from B3 in September putting them at “very high default risk” and say there is a one-in-three chance they will be downgraded again in the next year.

If the EU-Ukraine pact is signed, and the Kremlin does retaliate, the EU has plans in place to supply Ukraine with natural gas, as well as arrangements with the IMF for emergency financing. Russia’s reaction could be a trade blockade, which could cost cash-strapped Ukraine as much as $2.5 billion in 2013.

Putin’s economic aide, Sergey Glazyev, argues signing the contract would be a breach of Russia and Ukraine’s Treaty of Friendship.

Medvedev says Russia “isn’t jealous” of Ukraine’s decision to

join the EU and joked that their neighbor is welcome to enter the

throngs of Europe’s deep recession, and develop along the lines

of Greece or Cyprus. .

“Signing the agreement would be positive for Ukraine’s trade over the long term, but there could be short-to-medium-term negative implications largely related to Russia’s reaction,” Dmitry Trenin, Director of the Carnegie Moscow Center, told RT in an email sent on Friday.

Whether Ukraine is successful at Vilinus or not, Putin will ramp up efforts against Yanukovich, who faces reelection in 15 months.

“If there is no deal in Nov 2013, Putin will have won a

resounding psychological victory – most everyone in the EU would

want to prevent that, and Yanukovych counts on it,” Trenin

said.

“Russia has set sights on the 2015 elections in Ukraine and intends to help a pro-Russian leader to power. Ironically, however, the more pressure Russia applies on Ukraine, the less likely it will succeed. Even more ironically, this will be in Russia’s own best interest – the last thing it should want is Ukraine in the Customs Union,” Trenin said.

The EU and the International Monetary Fund will likely need to

finance a $12 billion loan to Ukraine, according to a May 2013

estimate by The Goldman Sachs Group.

In Ukraine, bonds have hit fresh lows, currency reserves are

almost nonexistent, and there’s more than $60 billion in debt,

roughly a third of the country’s GDP, due by July 2014, according

to central bank data from July 2013.

The EU trade deal may not be able to prevent the grivnya,

Ukraine's currency, from going bust before elections, which could

open up political capital for Russia.

Free Julia

If Yanukovich doesn’t grant former Prime Minister Julia Tymoshenko a pardon by November 18, European ministers may delay Ukraine’s ratification until 2014.

“The refusal to release and free Tymoshenko threatens to disrupt the signing of the agreement,” Polish Foreign Minister Radoslaw SIkorski was quoted saying on the Polish television program, Polsat News on Oct 31. He urged the Ukrainians ‘not to waste time’ with Tymoshenko’s release.

Tymoshenko was jailed for a gas deal she brokered with Russia in

2009. Her imprisonment is seen by European ministers as political

persecution. She was also charged with murder, an accusation that

was later dropped.

Her release would be symbolic and show that Ukraine is ready to jettison corruption, hold fair elections, and most importantly for EU ministers, end ‘selective justice’.

Tymoshenko, 52, has requested she be allowed to travel to Germany to receive medical treatment for spinal problems. Yanukovich has dismissed the idea of a pardon, but said he will sign any draft law that lets her take a ‘prison break’ to receive medical treatment abroad.

“The bill is still in the in the preliminary stages but if it is enacted, it will be seen positively by the EU and have significant influence for Ukraine’s acceptance. It’s a temporary alternative for an amnesty act,” Aleksey Zorin, an attorney at ARMADUM lawyers, a Kiev-based international law firm, told RT by email on Saturday.

Since the Orange Revolution in 2004, the country has been gravitating towards integration with Europe, becoming more disillusioned with its greatest economic benefactor, Russia.

Drifting East and Russia’s Customs Union

Putin has been rounding up ex-Soviet states to join Russia in a Eurasian block with promises of lower gas prices and other trade perks.

Russia, Belarus, and Kazakhstan met in Minsk on October 24 to discuss the formation of a Eurasian Union in 2015, a political and economic alliance which will incorporate other Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) like Armenia, Tajikistan, and Kyrgyzstan.

50 percent of Ukranians, 57 percent of Armenians, and 59 percent of Georgians want to join Russia’s Customs Union, according to a Eurasian Development Bank survey published on September 24, 2013.

Membership in the EAU entails uniting economies, legal systems,

and customs services - and military coordination with Russia. In

order for the ambitious plan to work, Russia needs to lure

strategically important nations like Ukraine into the trade

circle.

Other Soviet satellite states have chosen to instead hang their hat with Europe.

Poland, Ukraine’s co-host for the 2012 EuroCup, entered the EU in

2004, and like Ukraine, was seen as a ‘swing’ state, as their

membership wasn't a sure thing. Romania and Bulgaria have been EU

members since 2007, and Croatia joined this year.

Armenia, Poland, Moldova, and Azerbaijan will join Ukraine at the Eastern Summit in Vilnius on November 28-29. They also face the decision of joining Russia’s trade bloc, which the EU sees as ‘incompatible’ and grounds of rejection for EU membership.

Armenia said it would join Russia in the Customs Union, as well as engage in the Eurasian integration process, instead of negotiating a free trade agreement.

Ukraine’s ascension to EU membership could be another 15-20 years

down the road, and might be derailed by a number of factors- a

pro-Russia president taking power in 2015 or even discord from

within the EU, as some ministers doubt expansion is a sound

strategy during economic recession.

Turkey’s progress towards EU membership has been at a stand-still

since it first applied in 1987 and still hasn’t made much headway

even after signing a free trade agreement with the EU in 1995.

Turkey is now considering joining the Customs Union.

If Ukraine’s ratification follows a similar trajectory, Ukraine’s Russian-leaning crowd, centered mostly in Kiev, Crimea, and eastern Ukraine, could make a case for going back to its historic trade partner.

Gas bill - $1 billion overdue!

Russia told Ukraine it could save $10 billion in gas discounts if it joins the Customs Union, but Ukraine wants to rid itself of its dependence on Russian energy.

Gazprom and Kiev’s Naftogas have a rocky payment and pricing history, and most recently, Gazprom demanded Ukraine urgently pay a $1 billion overdue gas bill.

“Ukraine has an extensive non-payment credit history for

Russian gas, mounting debt, and restructuring,” Aleksey

Grivach, deputy director of Gas Projects at Russia's National

Energy Security Fund, told RT in an email Friday.

“The situation is itself dangerous - Ukraine is poorly

prepared for the winter season,” Grivach told RT.

Earlier in October Naftogaz said it had 17 billion cubic meters

of gas stored up, which they believe will be enough to heat

Ukraine through the winter.

The gas debt payment request is not connected to Ukraine’s

possible associated membership with the EU, Putin’s press

secretary, Dmitry Peskov, told reporters on Tuesday.

Russia and Ukraine waged two gas wars over prices in the winters of 2006 and 2009 (which lasted 3 weeks) over a similar claim Ukraine was late on a payment.

If another gas war erupts over the current pricing tiff and Russia turns off the gas, EU officials said they will help with supplies to Ukraine.

This strategy would burden neighboring European states, as a supply crunch would bump up prices. It is also only palpable for a few weeks.

Under the leadership of Tymoshenko, the Ukrainian gas company signed a 2009 ‘pre-pay’ contract with Gazprom. Yanukovich, who has complained about the ‘unfair’ prices, has scaled down Gazprom imports 40 percent year-on year, and is instead seeking other energy suppliers.

After the collapse of the Soviet Union, Ukraine became a natural

hub for transporting Russian gas to European and Turkish markets,

but Gazprom, Russia’s state-owned gas giant, is building a maze

of new pipelines to circumvent their western neighbor in transit

logistics.

Gazprom, Russia’s largest natural gas company, ships half of its European gas through Ukraine. Transit through Ukraine stood at 61 billion cubic meters in the first nine months of 2013, while in FY 2012 the figure was at 84.2 billion cubic meters.

Louise Dickson, RT Business