Nightmare in Manipur: Peace remains elusive in bloody battle over land, identity politics as ethnic clashes singe Indian state

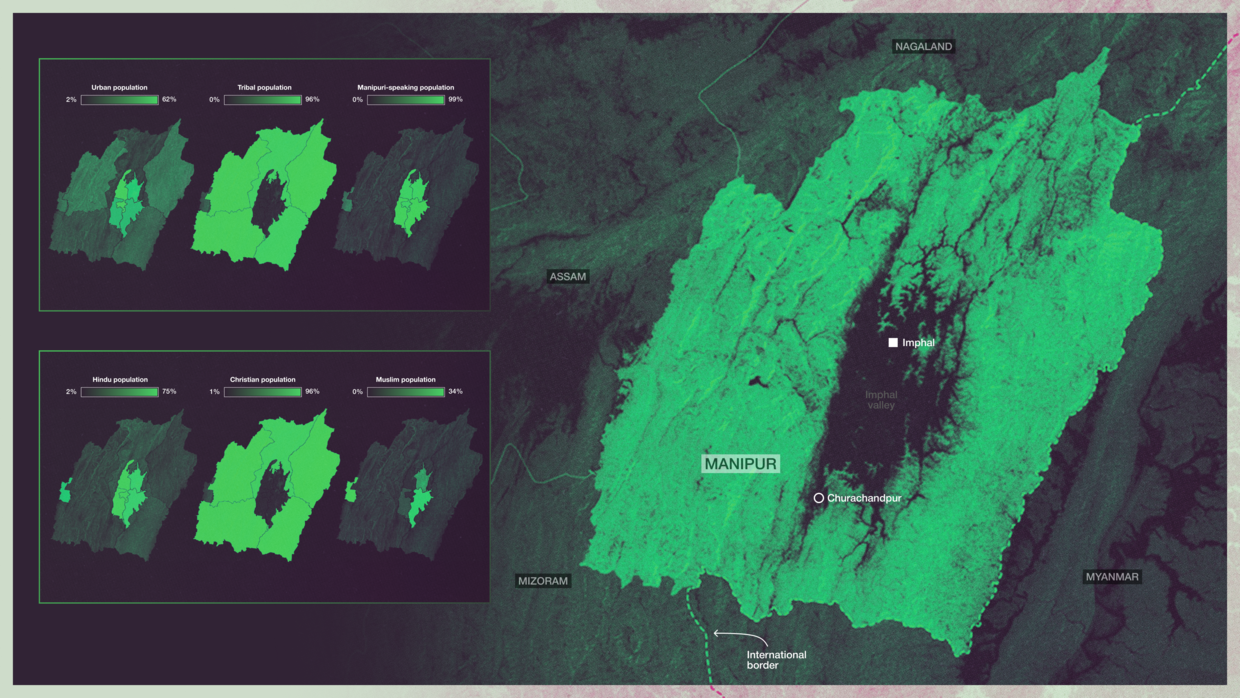

Manipur, the remote north-eastern Indian state, continues to burn weeks after the violence first erupted on May 3, following ethnic clashes between the majority Meitei community and the minority hill tribals, belonging to the Kuki/Chin/Zomi groups.

On Sunday, fresh clashes erupted between the two communities, and at least five people, including a policeman, were killed and 12 others injured.

RT Asia editor Joydeep Sen Gupta visited the Indian state to report on the genesis of the unending violence, whose local dynamics are inextricably linked to global narco-politics, amid fears of compromising India’s strategic cross-border interests.

‘Buried Alive’

David Liansiangoun, a scrawny Kuki lad and a daily-wage construction laborer, was given up as dead by Indian security forces after he was attacked by the rival Meitei community on May 4. This was a day after ethnic clashes erupted in the remote north-eastern Indian state capital, Imphal, and beyond in some of Manipur’s hill districts, including Churachandpur, the epicenter of the violence.

Liansiangoun, 22, was attacked at Kakwa, Singjamei, in Imphal Valley along with two of his co-workers and fellow tribesmen, Paolalmoun, 19, and Lalneu in his mid-30s. They were allegedly made to stand in a nullah (a riverbed or ravine) by the Meitei aggressors and their legs were tied with ropes as blows rained on them from all sides.

Liansiangoun’s father T. Khupminthang, a resident of Zoumunnom, a Kuki village half a kilometer (km) from Churachandpur district town, recounted his son’s ordeal. Two weeks after the incident the victim was still in a state of shock at the Churachandpur District Hospital, when this correspondent met him. He has also suffered speech impairment because of his multiple injuries.

“My son can’t recollect the incident in a chronological manner. He suffered seven cracks at the cranium, jaw and chin bones and also hit on the left side of his head. There are scars on his right ribs, which indicate that he must have been dragged on the pavement and left to die on the road at Kakwa. The police thought my son, who had lost his consciousness, was dead and kept him at the morgue in the Regional Institute of Medical Sciences (RIMS) in Imphal.”

The father continued “Fortunately, he was found to be alive by the morgue authorities and was shifted to an intensive care unit (ICU) bed in the hospital, where he stayed till May 10. We had no clue about his whereabouts since he did not carry a mobile phone. My wife received a call from an unknown mobile number at around 1:30pm on May 10. My son managed to get hold of a mobile phone from one of the nurses and called his mother pleading us to take him back home. The following day, he was shifted back to Churachandpur District Hospital with the help of Indian Army personnel. He has to undergo treatment for a few more days before he can be discharged by the hospital authorities.”

Liansiangoun’s plight illustrates the deep ethnic fault lines that have engulfed Manipur as both the warring groups — the minority Kuki/Chin/Zomi and the majority Meitei community — are seeking a bitter separation from each other.

Help thy neighbor

The youth from the Kuki/Chin/Zomi tribes have emerged as saviors for their hapless and poor community members, who live off forest produce, subsistence farming and daily-wage labor.

Manipur, like several other north-eastern states, suffers from very high unemployment, boasts little industry to speak of and has a negligible middle class, unlike mainland India.

Kennedy Haokip is information and publicity secretary with Kuki Khanglai Lawmpi (KKL), a philanthropic organization which has teamed up with other like-minded outfits from smaller tribal bodies to emerge as a first-responder unit. They focus on tackling the humanitarian crisis in Kuki-majority Churachandpur district, where fear and mutual distrust hold sway, even though the district headquarters is located only 65 km away from Imphal.

The battlelines have been sharply drawn at Torbung Bangla — on the border of Bishnupur and Churachandpur districts and which bore the brunt of the violence on May 3.

The KKL and other tribal youth outfits are taking care of those displaced by the violence. Many of them — mostly women and children as the men are left to guard the villages — live in over 50 rescue and relief centers in Churachandpur district. Churches of various denominations that form the backbone of tribal life have also emerged as the other lifeline for the distressed.

Haokip told RT about the growing challenges in organizing rations, potable water, blankets and clothing for the internally displaced who lost all their belongings in the overnight armed raids.

“The biggest worry is the shortage of medicine. The government aid is not adequate as more people, who are living in constant fear, are abandoning their homes and seeking shelter in anticipation of fresh attacks,” Haokip said.

In the early 1990s, Manipur and Churachandpur district, in particular, had acquired the dubious distinction as the HIV/AIDS capital of India. Intravenous drug use has been rampant due to the availability of narcotic contraband via the porous, 400-km border with neighboring Myanmar, ruled by a corrupt military junta, according to India’s intelligence agency sources.

“Though the AIDS scourge has abated significantly in Churachandpur, the antiretroviral therapy (ART) needed for the immunity disorder’s treatment is scarce because of the disturbances triggered by ethnic clashes,” the KKL leader added.

Manipur’s Nightmares

Lunthang, 41, a male villager, recounted that, “The Meitei armed groups indulged in looting and arson of 35 houses and up to 300 people were displaced at night on May 3. The villages of Gelbung and Haotak Vajang, which are adjacent to each other, were not spared, either. We fled from our homes via the hills at the dead of night and reached the vicinity of V Mouljang village, which is located around the Dampi forest area. The KKL volunteers brought us to safety here”

Saidan, a frontline Hmar village, proved to be a shield for the helpless villagers. The village chief Pu Rohminglien and secretary Zoneikung, along with volunteers, guarded round the clock in a bid to prevent the Meitei attackers from entering Tuibong in Churachandpur town, a predominantly Kuki neighborhood.

Similarly, in Siden, another frontline Kuki village, the chief, Thenkhosei Haokip, recounted how violence erupted at night on May 3, where the “Manipur Police commandos were reduced to passive bystanders, who came in bullet-proof vehicles and sided with the Meitei aggressors.”

Haokip alleged that four Kuki civilians were shot dead by the commandos, who, it is alleged, continued to riddle the bodies with bullets even after the victims were dead. The Kuki villagers suspect that the perpetrators were not commandos but members of a Meitei militia in disguise. They looted, torched and destroyed other nearby Kuki villages such as Lailampat and Minjang.

Jangkhopao, 54, a male Kuki and a resident of Lailampat village,which is located around five km away from Siden, was locked and burnt to death inside his house.

Luckily, though, Seikhomang, 41, having been caught by the rioters, managed to beat a hasty retreat, even though around 16 houses in his village were razed to the ground.

Kamsei Haolai, the chief of Haolai Khopi village, made a passionate appeal for restoration of peace and normalcy.

He said, “The Kukis are a minority community as compared to the majority Meiteis. They have all along discriminated against us and now they want to eliminate us. Through the years, they have come up with several acts, rules and regulations and legal loopholes to curtail our rights. They are hell bent to drive us from our ancestral homeland…we have all along fought against colonial British rule to safeguard India’s sovereignty and territorial integrity. Our valor is well documented in our resistance against the British in the Anglo-Kuki War (1917-19). We can no longer live with the Meitei community. We are demanding a separate administration, which can be federally administered on the lines of Jammu and Kashmir and Ladakh since the abrogation of Articles 370 and 35A of the Indian Constitution.”

However Meitei people also see themselves as victims of these tragic events. Around 800 people, including children and the elderly, are living in pitiable conditions in relief shelters near Thangjing temple and Moirang Lamkhai in Bishnupur district in the Imphal Valley, which are being run by three Meitei civil society organizations.

The prevailing tension and hostilities that triggered the ethnic clashes are rooted in the endemic cycle of violence that has engulfed the underdeveloped state since its merger with the Indian union in 1949.

The endless cycle of violence

Manipur, known for its pristine beauty where rolling hills meet the lush Imphal Valley, has been long battling deep ethnic fault-lines amid a deceptive surface calm.

There has been a long history of the Kuki/Chin/Zomi community’s uneasy ties with other ethnic groups such as the Nagas, Chakmas, Reangs and Assamese.

In June 1995, the Kukis attacked the ethnic Tamils of Moreh, a trading outpost on the Indo-Myanmar border, which led to an exodus of the South Indian community from the area. The Tamils lived in erstwhile Burma during British rule.

The genesis of the ongoing spate of bloody clashes and mutual distrust can be located in years of lopsided local Congress policies, several Meitei community members told RT.

India’s federal government passed the Constitution (Scheduled Tribes) Order, 1950, which paved the way for so-called Scheduled Tribe (ST) status for the Naga and Kuki/Chin/Zomi communities but not the Meitei. Many upper caste members of the dominant group did not resent this, because of their superior social standing.

A decade later the Manipur Land Reform and Land revenue Act of 1960, which prohibited the purchase of tribal land by non-tribals in the state, hit the Meitei community hard. Then, the Manipur Hill Areas District Councils Act, 1971, gave increased powers to the hill areas and put land under the jurisdiction of the Hill Areas Committee.

The successive legislation ensured that the tribals enjoyed land rights in the state, which had a population of about 3 million in 2011 and which is comprised of about 90% hill lands, and 10% by the Imphal Valley.

The Meitei community, who are adept at wetland farming, can buy land in the Imphal Valley, and the Jiribam plains, bordering Assam, the north-east India’s most populous state

However, the tribals are allowed to buy land in the plain areas.

Land rights and identity politics have been the flashpoint in the troubled state for decades.

For instance, on September 13, 1993, Naga militants allegedly belonging to the National Socialist Council of Nagaland (Isak-Muivah), which has been fighting for sovereignty for Naga tribes in several north-eastern states including Manipur, massacred around 115 Kuki civilians in Joupi.

Altogether, 1,157 Kukis were allegedly killed by Naga mercenaries during the 1990s. Similarly, there was bloodletting between Kukis and Paites — both tribes trace their origin to the Chin state in Myanmar — in the same decade.

The Hindu Meitei and the Muslims from the same community, too, had clashed in the 1990s, and echoes of this event are being felt in the current ethnic crisis.

India’s federal government has tried to govern the disturbed state by imposing the draconian Armed Forces Special Powers Act (AFSPA) in 1981, to quell the ethnic unrest in the Imphal valley. The law, which grants virtual immunity from prosecution to Indian military stationed in the border state, was expected to be in force only for a year, but the Naga insurgency put paid to its withdrawal.

The Malom massacre, which occurred near Imphal’s Tulihal airport on November 2, 2000, led civil rights activist Irom Sharmila to go on a hunger strike for 16 years following the Indian Army’s murder ot 10 helpless civilians who were waiting at a bus stop.

Sharmila emerged as a symbol of protest against the Indian Army’s misrule, despite her obvious lack of political understanding, until “the slight, pale woman with unruly dark hair” gave up her relentless non-violent fight against the armed forces and retreated to Bengaluru for domestic bliss.

However, Sharmila’s solo fight against the Act failed to stop Indian Army atrocities, which came to a head in the wee hours on July 11, 2004. The body of a Meitei lady, Thangjam Manorama, 32, who had been picked up the previous night from her home in Laiphorak Maring by Indian Army personnel, was found naked the following morning near her home. Her body was riddled with bullet wounds and badly mutilated.

The Indian Army maintained that Manorama was picked up as she was a member of the separatist proscribed group People’s Liberation Army (PLA) and was responsible for several bomb blasts, including one that killed several Indian Army officers.

Soon, there was an outcry to repeal the Act from the state, but the Indian government refused to pay heed to the pleas.

On July 15, 2004, 12 imas, or Meitei mothers, flung their clothes off outside the Kangla fort — the traditional seat of Manipur’s governance and the Indian Army's local base — to protest the rape and murder of Manorama, amid spontaneous chants of “[Indian Army] Rape us, kill us! Rape us, kill us!”.

In 2012, India’s Supreme Court (SC), took cognizance of 1,528 extrajudicial killings in the state over the last 30 years and both the federal and state government’s apathetic attitude towards them.

Years later, human rights activist Babloo Loitongbam, Director of Human Rights Alert Manipur, alleged that police intimidated the witnesses in the fake encounter cases.

Justice still remains elusive for the victims’ kin, as only as recently as mid-May amid the fresh ethnic clashes, the SC, after all these years, has given an ultimatum to the state government to dispose of the matter in the next three months.

What does the Manipur government say?

The civil war between the dominant Meitei community, who are largely Hindus and the Christian Kukis has plunged the state into further chaos and anarchy.

The current crisis is steeped in the socio-ethnic landscape of the state, where the Meitei community is not a homogenous construct. Up to to 9% of Meitei follow Islam and are known as Pangals. A vast section also embrace Christianity because the faith opposes social discrimination and also offers several safety nets such as free education, healthcare and other benefits that are largely absent this remote state that has been living under the shadow of a gun.

Half-truths, lies and swirling rumors have taken center stage to ratchet up tensions among the two warring ethnic groups amid unimaginable hardships for the local population.

Food has become scarce and prices of essential commodities have skyrocketed since the ethnic clashes began A curfew is still enforced by the Indian Army and paramilitary troops; the internet, a lifeline, remains suspended; and schools are closed till May 31.

The crowded Thangal and Paona Bazars are deserted, as most shops are closed. Over 30,000 people remain stranded in crowded and unsanitary refugee camps. Thousands of Kukis have fled to neighboring Assam, Mizoram, Nagaland and scores managed to take the few flights to mainland India for safety, despite an unprecedented spike in air fares.

Nongthombam Biren Singh, the 12th Chief Minister (CM) of Manipur, who is believed to have been championing the development of the remote landlocked state for the last six years, now finds himself at the center of the political storm amid talks of his chair is being rocked by his rivals within the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP).

Six years of the CM’s hard work is seen to have gone down the drain because of two days of bloody clashes.

Singh, a former footballer, journalist and now a politician, has been blamed for inciting the violence and incurring the Kukis’ wrath for eyeing their land rights in the hill districts such as Kangpokpi, Churachandpur and Tengnoupal. The CM has been blamed for inciting his community members to leave their respective “Leikais” (neighborhoods in Manipuri language) in the plains and head to the hills, which is the homeland for the Kuki/Chin/Zomi and Naga tribes.

However, in a complex state such as Manipur, the torturous past disrupts the present and often portends an uncertain future.

Thounaojam Basanta Kumar Singh, Manipur’s minister for education, law and legislative affairs and a spokesperson for the government, spoke to RT of “Our sincere commiserations for the May 3 incident.”

He put the chain of events that led to indescribable suffering for a vast section of the population in perspective.

“Manipur is home to diverse, multi-lingual, multi-cultural and multi-ethnic groups of which as many as 34 are recognized by the government. However, of late, it has become a mini Indian Golden Triangle. The porous borders with Myanmar are being used as a conduit to smuggle large quantities of contraband into mainland India via Manipur. Our state has become a major drug manufacturing hub because of rampant poppy cultivation in the hill districts. The state government has been pulling out all stops to eradicate the drug menace that has lost an entire generation to lethal addiction. The fight against the drug mafia is also to save India’s vast youth population — our pride in demographic dividend — as the contraband are known to find their ways in big urban centers such as Delhi, Mumbai, Bengaluru, Chennai etc.”

Singh, a retired police official and a member of the Cabinet sub-committee that has been set up to prevent illegal immigration from the military junta-ruled Myanmar, said that he and his colleagues have been tasked with identifying illegal immigrants, who have been infiltrating into Manipur.

Illegal immigration — a socio-economic and political hot button issue in Manipur — is an oblique reference to the Kuki/Chin/Zomi tribal groups, who the Meitei community accuse of changing the demographic contours of the state.

The non-Naga hill tribals’ population is estimated to have ballooned to around 30% from a paltry 2-3% in 1901. The population of Naga tribes, of which the Tangkhuls and Zeliangrongs are the majority, is estimated to be around 15% and believed to have remained largely constant in the past two decades. The Nagas are neutral in the ongoing conflict, but the crisis would likely deepend further should they mobilise.

Singh claims that illegal immigrants, of which 2,300 have been identified to date, would stick out like a sore thumb as they are not proficient in any local languages or dialects, despite having legitimate documentation to pass off as Indian citizens.

“Successive previous governments have turned a blind eye to these festering issues. The vested interests never paid any attention to the aggrieved folks’ cause,” he added.

Manipur’s long-running insurgency has also led to an entrenched parallel government, where the rule of law has been the biggest casualty.

The minister was at pains to point out that “no other state should interfere in the internal affairs of Manipur” and the clashes should not be seen through a “religious prism”.

He maintained that dialogue would be the only way forward to restore peace and normalcy.

The state government data underscored the demographic changes because of the consistent influx of the Kuki/Chin/ Zomi refugees from Myanmar since the military junta retook power in 2021 (they had been in power from 1962 to 2011).

The BJP-led government also maintained that no singular ethnic group or community was targeted since it came to power in 2017.

The authorities also point to the ongoing struggle to end poppy cultivation in the state and attempts to weed out the entrenched cross-border drug mafia, whose long tentacles stretch from Southeast and South Asia to Europe and Eurasia, including Russia.

Kukis do have a history of violence with other tribal communities, including Hmar (1959-60), Paite (1997–98), Dimasha (2003), Karbi (2003-04), Naga (1992-97) and now Meitei.

Incensed Meitei civil society groups have pointed out that the Kukis, as a nomadic tribe, do not carry much collective memory. “Neither do they have respect for others’ memories. For them, wherever they go becomes their land as they live off shifting cultivation. Fertility of the soil shapes their migration pattern. This wandering lifestyle takes them very often closer to the habitation of other tribes/communities, leading to friction,” they argue.

The strife, as pointed out by the ruling BJP’s legislator, Nishikant Sapam, a Meitei himself, is really over land rights.

Dr. Ratan Thiyam, an eminent playwright, who belongs to the Meitei community, has spoken out against the violence and appealed for immediate restoration of peace and normalcy.

He also expressed his disappointment over the weakness of the intelligence network of the state. He said, “Had the intelligence alerted about the violence in time, the present situation could have been avoided.”

What do the Kukis want?

In an unprecedented move, 10 Kuki/Chin/Zomi members of the state legislature (MLAs) have struck a discordant note.

The MLAs, including two ministers of the Singh-led right-wing BJP government, urged the federal government to carve out a “separate administration” under the Indian constitution and let people from their community “live peacefully as neighbors with the state of Manipur”.

Interestingly, seven of these MLAs who are signatories to the press statement issued on May 11, belong to the ruling BJP, two are from the party’s alliance partner, Kuki People’s Alliance (KPA), and one is an independent.

The Narendra Modi-led federal government has been in peace talks with the Kuki armed groups, who are demanding a separate Kuki state, since 2016. The most recent clashes have only revived the statehood plea.

On Sunday, CM Singh said at a press conference that 40 Kuki insurgents had been neutralized by the security forces during intense encounters across the state. However his announcement is seen as an “anti-Kuki statement” and has snowballed into a political controversy, as the CM is seen to be siding with his Meitei community.

The violence is this beginning to derail the BJP government’s reforms agenda.

The BJP government is all set to lift a liquor ban (prohibition was introduced in 2001) in the state to earn the much-needed revenue, expected to reach 7 billion rupees ($84 million). It will also combat the consumption of illicit alcohol in the “wettest dry state” that has led to an exponential spike in liver and kidney diseases among a large section of the population.

The state government’s reforms are likely to be stalled because its own Kuki legislators are hellbent on confrontation and calling for separation.

The Kuki MLAs, who have fled to neighboring Mizoram and New Delhi, have charged two prominent members of the Meitei community, CM Singh and a member of the Upper House of Indian Parliament, Leishemba Sanajaoba — the titular king of Manipur — with masterminding the recent carnage by sponsoring two little-known Meitei organizations — Arambai Tenggol and Meitei Leepun.

Intellectual voices within the community, such as L. Lam Khan Piang, who teaches sociology at the University of Hyderabad, have debunked the Meitei community’s ST status demand.

He pointed out that the exclusion was their own choice, an observation that is privately acknowledged by a vast section of the upper crust community members.

The country’s federal home minister Amit Shah, who is in charge of internal security, arrived in Imphal on Monday for a three-day visit to resolve the crisis.

However, concerns were raised underscoring a recent US report of lack of religious freedom in the country.

The Kukis living in faraway Tulsa, Oklahama, launched a solidarity march. Israel, too, is monitoring the situation after at least one member of the Bnei Menashe community, who claim descent from one of the ancient Israelite tribes, was killed in the violence.

What’s the way forward?

Civil society groups — the bedrock of one of India’s forgotten states — have a roadmap for the way forward.

As Dhiren A Sadokpam, editor-in-chief at The Frontier Manipur, a digital platform, has cogently argued, the local dynamics of the ethnic conflict are inextricably linked to a larger cross-border geopolitical narrative that is likely to have wider far-reaching ramifications.

And the reality lies while shifting through the claims and counter-claims of both the communities.

Fire-fighting is the immediate requirement, including disposal of victims’ bodies that are rotting in hospital morgues for several weeks now.

The various arms of the Indian government, such as external intelligence, Research & Analysis Wing (R&AW); Intelligence Bureau (IB); the Indian Army and other paramilitary forces need to be on the same page with a cohesive strategy to quell the simmering violence.

One more Meitei life was lost last week while angry protesters vandalized the house of state Minister for Public Works Department (PWD) Konthoujam Govindas in Bishnupur over alleged government inaction to protect the locals.

A judicial probe must be ordered under the chairmanship of a Supreme Court judge. The federal government must abrogate the Suspension of Operation (SoO) pact with all Kuki militant groups, as they may freely move while carrying arms. According to Meitei civil society groups the armed Kukis are also responsible for multiple violent incidents involving the general public.

The National Register of Citizens (NRC) must be immediately enacted to detect the Myanmar nationals and the guilty must be booked.

The Manipur Land Revenue and Land Reforms Act, 1960 must be revisited in a bid to suit the interest of all the communities without comprising equal access and ownership.

The Modi government must prioritize border fencing and negotiate with its counterpart in Myanmar to regulate cross-border movement.

There must be a proper policy on refugees. Designated camps must be established to settle incomers. Absorption of population from the neighboring countries such as Myanmar and Bangladesh due to ethnic conflicts, identity politics, or economic and livelihood crises should not be permitted.

Lastly, stability in Manipur can only be sustained by strong, grounded, and all-inclusive social and economic measures that preserve ethnic and demographic balances.

But the moot point is: will the aggrieved ethnic groups come to the table and smoke the peace pipe?

Perhaps, but only if New Delhi is willing to lend a helping hand.

And distance from the power center should not make the heart go cold amid PM Modi’s Act East policy outreach.