Will the BRICS expansion stumble over internal divisions or help bridge them?

The most important outcome of the BRICS summit in South Africa is the decision to expand the group. Six new members will join it on January 1, 2024: Saudi Arabia, UAE, Egypt, Argentina, Iran, and Ethiopia, which more than doubles the original membership. It is a transformative outcome.

Originally, RIC (the Russia-India-China group conceived in 1998) and BRIC were a response to the emergence of a unipolar world following the dissolution of the Soviet Union. BRIC, comprising four economically rising powers (Brazil, Russia, India, China) from three continents, shared the agenda of making the global order more democratic and equitable, reforming the United Nations system, including its political and financial institutions, increasing the role of developing countries in the global system, promoting multilateralism with the UN as its centerpiece, and so on. South Africa was not a rising economic power but its 2010 inclusion as a major African country had the rationale of expanding the coverage of BRICS to four continents.

The world is no longer unipolar, though the US remains the world’s leading political, military, and economic power. Its failure to change the map of West Asia in its favor by regime change through military intervention or democracy promotion through the Arab Spring, or the disastrous end of the War on Terror exemplified by its retreat from Afghanistan, has reduced its international primacy. It now sees the need to strengthen its alliances in Europe and Asia to retain its global pre-eminence. This includes the reinvigoration of NATO in Europe, as well as the alliances with Japan, South Korea, and the Philippines in Asia, not to mention the political and economic role of the G7.

While the unipolar phase is over, new tensions have arisen with potentially dire consequences for global peace and security in both Europe and Asia. The US is now pitted against both Russia and China, obtaining full support from Europe against Russia and acknowledgement of a systemic threat to Europe from China. The US has not hesitated to use its financial power to the hilt against Russia in an effort to isolate it and cause its economic collapse, and has gone to the extent of openly subscribing to the idea of regime change in Russia, a peer nuclear power. The US now sees China as its principal longer-term adversary and is taking steps to thwart China’s technological rise.

These tensions are affecting the international system. The drastic nature of the Western sanctions on Russia, especially the American weaponization of finance and the dollar as the world’s principal reserve currency, has, besides its very disruptive effects on the supply of food, fertilizers, and energy to developing countries, raised serious questions about the equity of a global order based on rules set by the powerful and not emanating from the collective will of the international community.

The evolution of RIC into BRIC and then BRICS always had the promotion of multipolarity as a core agenda. Everything else (reforming the international system, giving developing countries greater say in global governance, promoting respect for different political and economic systems, exposing the double standards of the West with regard to human rights and democracy, opposition to the West forcing its worldview on others as ‘universal values’) depended on diluting the West’s traditional hegemony through the emergence of new power centers and the resultant distribution of global power.

The West’s confrontation with Russia and China, the two most powerful members of BRICS, explains the group’s drive for expansion. Adding more members is seen as a tangible movement towards multipolarity. That Saudi Arabia, UAE and Egypt, and Argentina, with their strong Western links, are signaling their willingness to be part of this transition shows how the mood in the Global South is changing. These countries want to reduce their dependency on the West, widen their foreign policy options, and be able to better resist Western pressures by joining multilateral groups that seek to counter the West’s hegemony over the current international system. They see value in joining a group of major non-Western countries which seek to re-balance a global political and economic system whose rules and standards have been determined by the West and enforced with punitive costs for transgression.

The inclusion of Iran – which is already a member of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization, subject to Western sanctions, increasingly close to China and Russia, and at loggerheads with the US over nuclear, missile and regional issues – would have been inevitable in any expansion of BRICS’ geographical area of influence. On the other hand, Ethiopia, riven with civil war and economic distress due to prolonged drought, does not seem to have any plausible credentials to merit inclusion, other than its close partnership with China.

This raises the question of the criteria used for deciding on expansion. Were GDP size, growth prospects, population size, geographic location, or degree of regional influence part of the criteria? Barring Saudi Arabia and the UAE, which are economically strong and are large producers of oil with major expansion plans as part of their 2030 Economic Vision, the other countries face serious economic problems and can hardly be characterized as emerging economic powers. Egypt’s economy is also under stress, but Egypt, as a major political, military, and cultural Arab power, and the biggest in terms of population, is critical for maintaining a balance of power in its region. Its inclusion has an important political resonance at the international level. Argentina is facing a serious economic crisis too, but it has the distinction of being the second largest economy in South America, after Brazil, and a member of the G20.

Surprisingly, BRICS expansion does not include any Asian country. Indonesia was a candidate and would have been an obvious inclusion on all parameters, but it appears it withdrew its candidacy at the last moment in order to weigh the pros and cons of membership. It is possible that its last-minute hesitation may be on account of external pressure and considerations of cohesion within ASEAN. In Africa, Nigeria would have been a far more creditable candidate than Ethiopia, but its vice president says it did not apply for BRICS membership. Neither did Mexico, which would have been another plausible candidate from Latin America. The absence of Algeria, which had applied for membership, is notable. As it stands, the expansion is regionally lopsided, with four of the six new members from one region.

The summit’s joint statement adds to the confusion over the criteria in stating that the BRICS leaders tasked their “Foreign Ministers to further develop the BRICS partner country model and a list of prospective partner countries and report by the next Summit.” The reference here is not to new members but to a “partner country model” and “prospective partner countries.” If the criteria have already been agreed to and the announced expansion is based on them, why is there need to “further develop the BRICS partner country model”? Is the present expansion essentially ad hoc then, as consensus was possible only for the six countries in question?

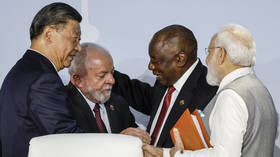

While expansion no doubt boosts multipolarity, will it make the new grouping less cohesive? Even earlier, BRICS had problems of internal cohesion, especially with continuing India-China differences. The two countries are involved in a military stand-off on the border, which contradicts many of the principles that BRICS espouses. Brazil’s commitment to BRICS under President Jair Bolsonaro was not as strong as that of President Lula before him. The fact that President Putin could not personally attend the summit in Johannesburg because South Africa could not reconcile its obligation to BRICS and to the International Criminal Court shows that the group is not entirely in control of its collective vision.

Now, with additional cleavages and rivalries entering the expanded BRICS grouping, such as those between Saudi Arabia and Iran, the UAE and Iran, Egypt and Ethiopia, Egypt and Iran, and also to a degree between Brazil and Argentina, will it make consensus building within the grouping more difficult, or reduce it to the lowest common denominator? On the other hand, can the expanded BRICS help in bridging these divides? It remains to be seen.

India has welcomed the expansion as it will strengthen the grouping and increase confidence in the idea of a multipolar world order. Prime Minister Modi has said that India enjoys warm relations with the six countries that are joining. India has a strategic partnership with five of the new entrants, and traditionally very close ties with Ethiopia. In Modi’s view, the new BRICS will be – Breaking barriers, Revitalizing economies, Inspiring innovation, Creating opportunities, and Shaping the future.

The statements, views and opinions expressed in this column are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of RT.