On the 154th anniversary of the birth of my paternal grandfather, Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi, on October 2, which is also celebrated as the International Day of Non-Violence, I think it is fitting to understand the relevance of the “Apostle of Peace” in a fractured world.

Gandhi has evolved into a timeless idea, whose relevance goes beyond India, his country of origin. A global search has long been in progress to understand his values and ideals. The world will be a better place if we live up to his experiments with truth.

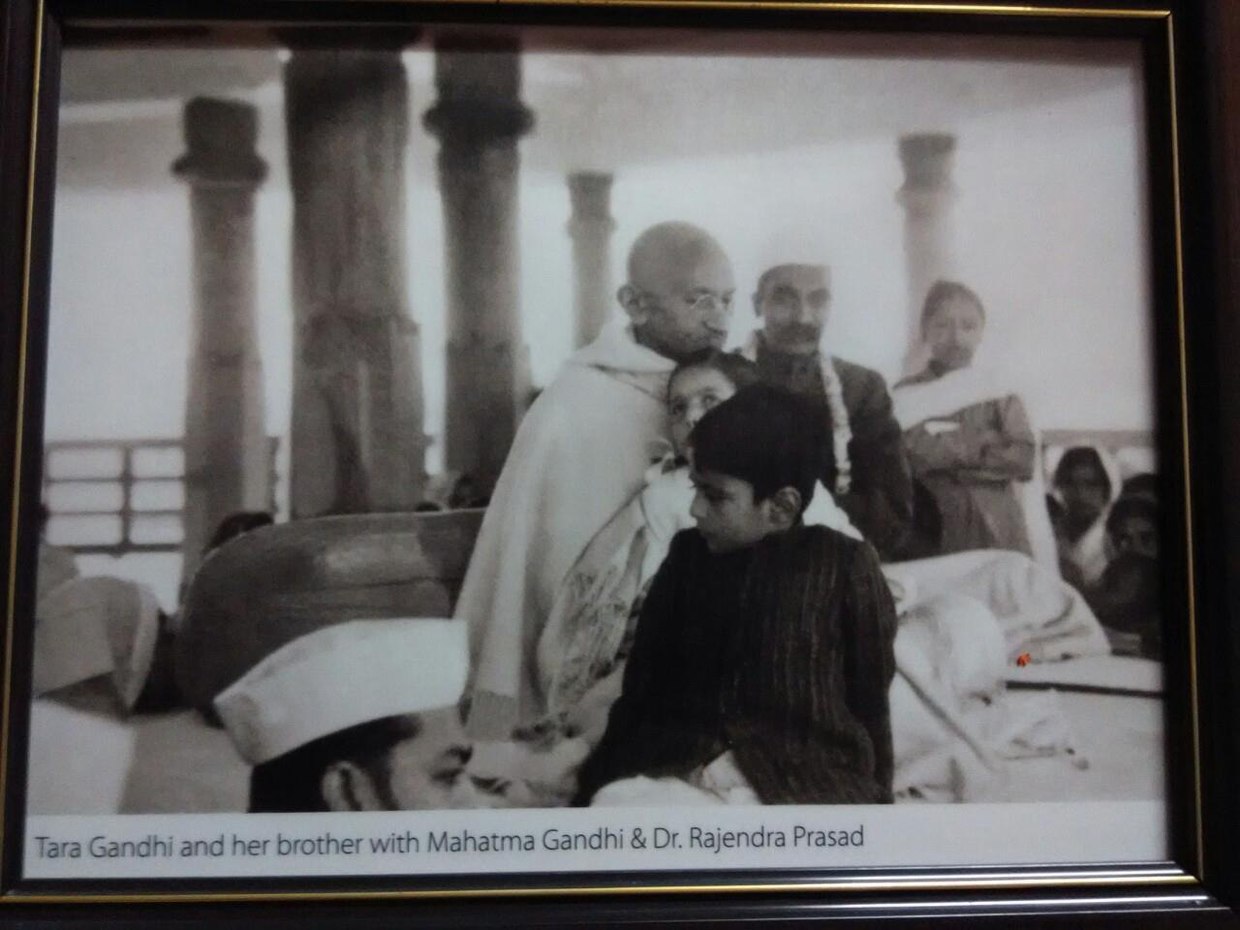

I consider myself fortunate to have spent the first 14 years of my life with him – Gandhi was assassinated by Hindu fanatic Nathuram Godse in Delhi on January 30, 1948 – and in my advanced years, I am still coming to terms with his lofty values and ideals.

To an impressionable young girl, who was unaware of the trappings of modern-day technology, gadgets and gizmos, he had tried to instill in me an inner quest for that elusive moment with truth in his inimitable ways.

As a doting grandfather, he would often ask me how I was improving my handwriting, what new knowledge I had acquired, and whether I was doing my daily physical exercise. I continue to cherish those simple joyous moments of life.

Gandhi’s is a celebration of an exceptional life: full of adventure. It was “Sattvik Shakti” (Sanskrit for pure spiritual energy). Even now, more than 75 years since his passing, I’m still possessed by his beatific smile and the inner strength of his spiritual energy.

The world may like to remember him as an advocate of non-violence. But to my mind, he was a philosopher and spiritual leader, who selflessly dedicated his life to forging a consensus.

The partition of the Indian subcontinent into two countries (India and Pakistan) at the stroke of a young nation’s independence in 1947 pained him immensely as he could not come to terms with the petty craving for power and wanton greed for materialism. It was a blow that he could never recover from till his tragic end.

At the end of his life, Gandhi was disappointed. He felt that though India gained political independence from the British, the country was unable to eradicate deep-seated injustice. The trend holds true in this day and age.

He was an internationalist, who had an exceptional ability to turn foes into friends like a clinical psychologist. He could read people’s minds with consummate ease while never, ever compromising his own conviction.

Perhaps this fascinating strength of his character came into its own during his non-violent fight against colonial British rule through his civil disobedience movement, which had started in 1930.

I have realized that Gandhi is a symbol of Everyman. He believed that non-violence and peace are a celebration of our consciousness to honor life and creation. This celebration of our consciousness should be translated into the objective of a people’s movement for cleaning the human mind of violence and protecting the environment from pollution. This celebration is a universal message that goes beyond social, political and religious divisions.

For Gandhi, non-violence meant much more than just a lack of violence. Non-violence is an action and introspection. It is the courage of truth with love. It is the reawakening of the spirit in harmony with nature and environment and all forms of life, whose significance has acquired an all-new dimension amid the global conversation around climate action and sustainability.

Consider his struggle for independence against the imperial British forces. It was the struggle of an ordinary colonized Indian in search of truth, liberation and independence. The genesis of his freedom movement, which appears to have been lost on many historians, is fundamentally rooted in economics. The British were busy plundering our wealth, such as textiles manufactured in our mills, which found their way to England while Indians continued to languish in poverty.

This led to the revival of khadi – the handspun and hand-woven cloth – and has since emerged as the thread of creation. Through the decades, khadi has become a source of livelihood and a fashion statement to millions of Indians. The “charkha,” a hand-spinning wheel and a defining image of Gandhi, is also a meditational therapy. Now, the world again needs to get acquainted with the fabulous texture of the handspun fabric and the hand-spinning wheel.

The “charkha” is also inseparable from Gandhi’s “satyagraha,” the policy of passive political resistance, which is epitomized in his mother power.

He was a mother in a wider connotation of the word. He was a symbol of a common man, who through his extraordinary heroic deeds transformed into a larger-than-life power and an enduring symbol of empathy and compassion.

British Prime Minister Winston Churchill, who had no love lost for Gandhi, had grudgingly described him as a “seditious Middle Temple lawyer” now “posing as a fakir” (an ascetic) at the Round Table Conference in England in 1931.

Gandhi, who wore a loin cloth and wrapped himself in a white sheet, braving the cold weather in England, had elicited a snide remark from Churchill. However, his support for the poor, his encouragement of boycotts of British goods, and his wish to eradicate religious differences and class distinctions were lost on Churchill.

Gandhi’s relevance would not have stood the test of time had it not been for his wife Kasturba, who predeceased him in 1944. At every stage of his life, Kasturba, who got married to him at the tender age of 13, questioned her husband’s moves. Her challenge strengthened his power of conviction, helping him to revisit his thoughts and ideals. Kasturba was his sounding board as a life partner.

Gandhi also had a great ability to keep in touch with people in a technology-challenged age. He was a die-hard family man, who loved to spend time with his children, grandchildren, and loved ones, and also built a network of loyal supporters, ardent admirers and skeptics by keeping in touch with them through letters and word of mouth.

The British underestimated the power of this “fakir” and bowed to his “satyagraha.” Gandhi’s ideals continue to inspire his followers and admirers – many of whom may not be acquainted with the intricacies of his fascinating life.

I shall be in Arunachal Pradesh, the remote and largest northeastern state in the country, on October 2 to celebrate the 154th anniversary of his birth. I am going to visit Arunachal at the invitation of Robin Hibu, the first Indian Police Service officer from the state, who plans to convert his residence into a Gandhi memorial museum.

Such selfless acts of dedication and devotion show that posterity has not forgotten Gandhi’s values and ideals. And as long as people like Hibu are among us, the Gandhian way of life will continue to ignite young minds.

(As told to Joydeep Sen Gupta, Asia editor)

The statements, views and opinions expressed in this column are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of RT.