The outgoing 2023 will be remembered in India as the year of many "proud firsts” – from emerging as the most populated country in the world (bypassing China), to becoming the first nation to land on the Moon’s south pole, to having the first female officer of the Indian Navy to take command of a warship.

Following a triumphant Moon mission and the prestigious hosting of the G20 Summit, India is poised to enter 2024 with a renewed sense of optimism for further economic expansion (it is aiming at a $5 trillion economy by 2025) and aspirations to play a bigger geopolitical role.

The nation’s allure as an investment hub remains robust, leveraging a skilled talent pool, homegrown technologies and innovations, and tailored central and state government policies to attract global companies such as Apple and Tesla. Peering into the future, the nation eyes attaining developed economy status by 2047. No wonder growth, infrastructure development, and investment have been at the center of the pitch to voters by the Prime Minister Narendra Modi-led Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), as the country heads into a 2024 general election.

In retrospect, 2023 was a year that witnessed pivotal moments defining India’s trajectory. Below is a quick look into key events that shaped the year for India.

Big achievements

On the cold side of the Moon

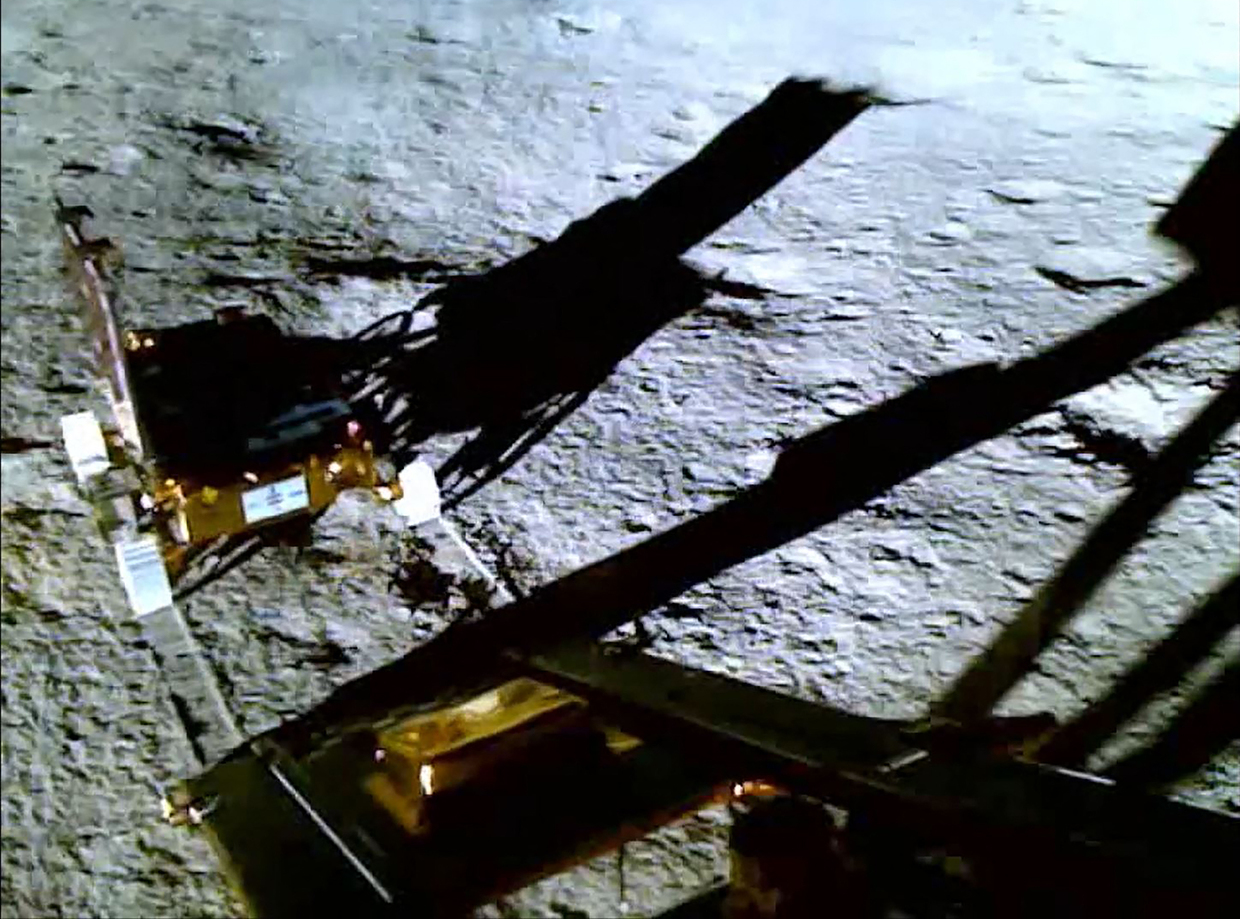

The Indian cow jumped over the Moon when its third lunar probe, Chandrayaan-3, became the first spacecraft to land on the lunar South Pole region. India joined the former Soviet Union, the US, and China as the only nations to have planted their flags on Earth’s satellite. The Moon’s south pole is thought to contain ice, so it’s a prime target for a possible lunar station and further research.

For Prime Minister Modi, it marked a moment he could declare “India is a superpower” – without other nations rolling their eyes. For Indian Space Research Organisation chief S Somnath, who had broken down in Modi’s arms when Chandrayaan-2 failed on a similar mission four years earlier, and the nation of 1.4 billion, it was a moment of supreme pride and triumph. ISRO even attempted to revive the mission in -200C temperatures at the Moon’s south pole, after the main mission’s targets were achieved, but to no avail.

By 2027, India will launch another mission to the Moon – to bring back samples from the lunar surface. Encouraged by the success of Chandrayaan and this year’s other breakthrough mission – to the Sun – Modi instructed ISRO to set up a space station by 2035 and send the first Indian to the Moon by 2040.

World’s first-ever sister-brother grandmasters

In August, Rameshbabu Praggnanandhaa (aka Pragg) nearly won the Chess World Cup in Baku, losing in a tiebreaker to Magnus Carlsson. Had he won, he would have become World Chess Champion; the only other Indian to achieve this was Magnus’s predecessor, Vishwanathan Anand (titleholder from 2007-13).

In December, elder sister Vaishali joined Pragg as grandmaster, when she crossed the 2,500 Elo threshold at a tournament in Spain. They became the world’s first-ever sister-brother pair to be grandmasters; there is a long list of brothers who became grandmasters, including India’s Vignesh NR and Visakh NR, who achieved this in February 2023. There are approximately 1,200 grandmasters globally, according to ‘The Chess Journal’; and India currently has a robust 82 grandmasters.

But the real star was Vaishali-Pragg’s mom, N Nagalakshmi, the modest Tamil ‘amma’ with a toothy smile who has been traveling and cooking for Pragg since he was seven. “I’m proud to hear people talk of my mother,” Vaishali said after his performance in Baku.

The great escape in Uttarkashi

Indian authorities rescued 41 men trapped for 17 days when the Sikyara-Barkot tunnel they were constructing in the Himalayan state of Uttarakhand collapsed on November 12. While reports suggested that regulations were overridden to construct the tunnel for the ‘Char Dham’ pilgrimage project – the fragile Himalayan ecosystem would have been better served with wider roads than the series of tunnels – the rescue was a tension-filled narrative with more twists and turns than a high-altitude road.

Authorities worked on six plans, the main being the use of an American Auger machine to drill six pipes through the debris to tunnel a way out for the trapped workers. The machine broke down twice. So they had to use a dangerous (and illegal) method of “rathole mining”, in which a tunnel barely wide enough for an emaciated human was dug to gain access to those trapped. Ultimately, an 80cm pipe was laid through which the trapped men crawled out. It was exemplary of Indian ‘jugaad’ (a hack) and persistence; and also a proud moment of self-belief.

G20 presidency, India-style

Held in September, the G20 Summit was showcased as a display of Modi’s brilliance and vision. The event at India’s refurbished trade fair grounds, Pragati Maidan, was a razzle-dazzle of high technology and higher acidity food. The roads were cleared of dogs, shanties, and journalists. People were ‘encouraged’ to stay home, though not like the Hangzhou G20 Summit, where the Chinese government paid citizens to take a bus out of town for a holiday.

Modi had the deliberations end a day early with a ‘clean’ resolution, termed by many as “win for India” but also a “win for multipolarity,” as the Delhi Declaration was adopted after achieving a 100% consensus over 83 paragraphs of the final communique, including on the Ukraine conflict that had no mention of Russia – thanks to the role of India’s negotiators, and to much of disappointment of Washington and its allies.

Not just the Delhi Declaration – at the G20 summit, the Indian leader swiftly inducted the African Union as a member before the Europeans could even blink; he championed the Global South even while vigorously clasping US President Joe Biden’s hands. Yes, a triumph of the will.

India snatched away the baton for presiding over the G20 from Indonesia and reluctantly passed it on to Brazil; but during 2023 the leadership milked it for as much mileage as it could. And it was rewarded by voters in Hindi villages, who openly declared while standing in line for their free foodgrain, “Modiji did the G20.”

It’s raining Indians

It was the end of April when India reached 1.45 billion souls, beating China to take the mantle of the most populous nation on Earth. It was around 50 years ago that the rapidly growing populations of the South were thought to be a concern for a planet whose resources were being depleted, and whose climate was perhaps changing – and not for the better. The good news is, of course, is that the planet will be around for another 4.5 billion years. The even better news is that nations like India are thinking in the direction of inhabiting the Moon and Mars, and possibly other worlds.

For India, a burgeoning population means a younger, more productive country that can challenge its neighbor to become world's new manufacturing hub. New Delhi, however, has a bigger challenge – poverty and literacy. This year, the UN lauded India for lifting 135 million people out of poverty in the past five years. In 2022, around 15% of the Indian population was living in poverty, compared to 24.8% in 2015-16. Also, in just nine years, India managed to provide a no-frills bank account, or ‘Jan Dhan,’ to 509 million people – a staggering achievement. This scale of financial inclusion would normally take 47 years for a country to achieve, experts note.

A mammoth new parliament of crows

The world’s most populous country presumably needed a newer building, never mind that the old one was number nine on the “ten most impressive parliament halls” or the “ten most beautiful parliaments”. (The Hungarian Parliament consistently ranks number one, in case you were wondering.) But it was associated with colonial architecture, and when Prime Minister Modi inaugurated the building, he said as much. “The new parliament isn't just a building, it is the symbol of the aspiration of the 1.4 billion people of India,” he said.

But the very first "winter" session held in the new building was marked with a controversy over security arrangements. On December 13 a couple of men in their 20s jumped into the chamber, on invitation by a regime legislator, and set off non-poison, all-colorful smoke canisters. The incident came on the anniversary of the 2001 attack on the Indian Parliament in which six police personnel, two parliamentary security staff, and a gardener were killed, as well as five terrorists.

The “mastermind” of the attack later surrendered, and a total of six people have been charged under India’s Unlawful Activities Prevention Act (UAPA) and the Home Ministry is also investigating the breach.The intruders now face terrorism charges, and when the opposition demanded a statement on the breach, most of its members were suspended. As the world’s largest democracy enters the new year with high aspirations over the 2024 general election, some in the political establishment felt that the new house of democracy came with a fresh approach to democracy in India, that is Bharat.

Not-so-high lights

The small pebble in the fast-walking national shoe

A prominent TV anchor once said India’s northeast suffered the ‘tyranny of distance’ from the nation’s center of political gravity. That is no solace for the victims of group clashes between hill-dwelling Christian Kukis and plains-dwelling Hindu Meiteis in Manipur, a small state on the border with Myanmar.

It started with one group that wanted welfare benefits extended to them – which the other group objected to. The violence began on May 3 and still continues; 175 people have been killed. A video of women who were raped and paraded went viral, creating national outrage. The opposition questioned the Modi-led government and the PM himself on their month-long silence, which was broken on July 20. Modi said the incident was “shameful for any civilized nation” and vowed that “justice will be delivered.”

The Supreme Court eventually pulled up the state government. The chief minister of the state appealed for both communities to adopt the path of “forgiving and forgetting.” On December 15, there was a grim reminder of the year’s events in Manipur, during a mass burial of 87 bodies (including a month-old baby that during the evacuation from a riot zone could not receive vital hospitalization).

Wrestling with one’s collective conscience

India was in headlines globally for a month-long protest of women wrestlers, including Olympic medallists, against the president of the Wrestling Federation of India (WFI), Brij Bhushan Sharan Singh. They accused him of sexual harassment. The authorities seemed to be unmoved: Singh is a powerful MP from the ruling BJP, influencing a clutch of constituencies in Uttar Pradesh, India’s largest state, the control of which is key to national power.

Once again, the Supreme Court had to step in and force a reluctant Delhi police to file a case; despite the watered-down charges that are meant to fail in court, Singh had to step down. The last straw, however, came in December, when Singh’s right-hand man was elected as his replacement at the WFI. Champion wrestlers like Sakshi Mallik tearfully quit the sport, and male wrestler Balbir Punia returned his Padma Shri award. The government finally reacted on December 24 by suspending the WFI and sacking newly elected leaders.

Targeted Diplomacy

The 1980s Khalistan movement for Punjab’s secession from India was a bloody and terrifying time that claimed the life of a sitting prime minister, the late Indira Gandhi. It was the first time that road checkpoints became part of Delhi life. The movement has died out in Punjab, but found a new home – in some Gurdwaras (Sikh temples) in the West.

In September, Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau alleged – in parliament – that Indian intelligence had masterminded the killing of a Sikh activist Hardeep Singh Nijjar in June, outside a Gurdwara in British Columbia. While India denied allegations, Trudeau’s move sparked an unprecedented diplomatic row. The two countries expelled each other’s intelligence officers, India ordered the withdrawal of 41 diplomats and temporarily suspended visa services to Canadians.

When two months later the New York district attorney filed an indictment against Nikhil Gupta and an unnamed Indian official for attempting to kill US citizen Gurpatwant Singh Pannun, India’s outrage was considerably dampened.

True, the US has no compunction about killing foreign citizens on foreign soil – the examples are innumerable. But the bully on the block doesn’t exempt even his new best friend; especially if that friend is doing a tightrope walk on Russia and Gaza. No wonder then, Modi told the Financial Times that “incidents” should not derail US-India bonhomie.

Death by cough syrup

Cough syrups manufactured in India were under scrutiny even in 2022, after the World Health Organization (WHO) issued an alert over four brands of cough syrup manufactured and exported by Indian drug maker Maiden Pharmaceuticals to The Gambia in West Africa. At least 69 children have died there from acute kidney injury that could be linked to cough and cold syrups.

The government tried to shoot down the “presumptuous” WHO for claiming that Indian cough syrups were contaminated. However, a similar case soon came to light in Uzbekistan, where the Health Ministry linked the death of dozens of children to the consumption of cough syrup manufactured by Marion Biotech of Noida in the northern state of Uttar Pradesh. The company had allegedly bought a chemical for its syrup – propylene glycol – from a Delhi-based trader that did not have a license to sell pharmaceutical products and only “dealt in industrial grade.” Months later, New Delhi ordered Riemann Labs in Madhya Pradesh state to cease operations following allegations that its cough syrup was linked to the death of at least six children in Cameroon in March 2023.

Pharma is a $50 billion industry in India, which labels itself the world’s pharmacy. Given the size of stakes involved, as well as India’s aspirations to lead the global South, the country’s drug regulator swung into action. It found that 50 cough syrup manufacturers failed to clear quality tests. In December, the Indian government prohibited the use of anti-cold medication combinations for children under four.

Train tragedy

Nearly 300 Indians died and 1,200 were injured – in the east India state of Odisha in June, when the high-speed Coromandel Express (Kolkata to Chennai) crashed into a goods train and its coaches derailed and collided with another high-speed train (Bengaluru-Howrah Express) coming from the opposite direction. India’s Ministry of Railways, releasing the official findings from a probe into the deadly incident, said a signal error led to the collision. The report concluded that if corrective measures had been taken after a similar failure in 2022, the tragedy could have been prevented.

The Indian railway industry is the backbone of the national economy. Over 1.4 million people are employed along its 67,850km of routes – and Indian Railways is the country’s largest employer. Ever since the British established the railways, it has been the most popular mode of transport in the country.

Gone are the days of general-class compartments and starting with Kolkata in the 1980s, city after city in India has introduced metro rail projects. The government is eagerly designing urban infrastructure projects, including the 741km Nagpur-Mumbai high-speed rail corridor, constructed at a cost of $20 billion, or PM Modi’s marquee project – the Vande Bharat hi-speed trains that “herald a new standard of rail service in the country.” But building next-century infrastructure can all be in vain if routine necessities such as track replacement, signal upgradation, and the induction of anti-crash technologies are ignored.

Here come the floods

No one in India denies climate change, but action has been slow, going by two ruinous flooding episodes – aside from the ‘regular’ flooding afflicting states like Bihar or Tamil Nadu. This summer, the Himalayan state of Himachal Pradesh saw 72 flash floods kill nearly 400 people and thousands of animals; in October, the Himalayan state of Sikkim saw flash floods that killed just under 100 people. In both cases, bridges, hotels and temples were washed away, providing mesmerizing viral videos. Yes, the world’s mightiest mountain range is a real victim of global warming.

In Himachal, the floods demonstrated the disproportionate snowmelt released by tourists and their cars, and how traditional architecture is superior to modern assembly-line houses when it comes to resisting nature’s might.

The Glacial Lake Outburst Flood (GLOF) at Sikkim’s South Lhonak Lake might have been unavoidable, but there was no early warning system that scientists have been begging for, mindful of the many hydroelectric projects successive governments have been in a rush to implement. As a result, the 1200-MW Teesta dam was destroyed by the floods. Development comes with a cost.

Where India Meets Russia – We are now on WhatsApp! Follow and share RT India in English and in Hindi