Lotus awakening: How a Soviet magazine could give a new voice to Palestinians

It is unclear when ‘Lotus’, a literary magazine of progressive Afro-Asian writers largely funded by the USSR, published its last issue after a successful run spanning two decades (1968-1991); but it was certainly a voice of the Palestinian people.

Professor Tariq Mehmood Ali teaches English at the American University of Beirut and is an award-winning novelist and a documentary filmmaker. A few years ago, he launched a project to restore the magazine’s legacy. The project involves curating, saving, preserving, and digitizing old issues, offering historical depth to the Palestine movement and potentially making the magazine accessible to a new generation of readers from Palestine and the rest of the Global South.

“‘Lotus’ resolutely opposed Zionism, seeing it as a racist tool of imperialism,” says Prof Ali, who has pored over innumerable issues of the magazine. He suggests that Palestinians would not have had such a raw deal if the publication was still in circulation.

‘Lotus’ championed the cause of the Palestinian Liberation Operation (PLO) and even passed a resolution on Palestine at its third Afro-Asian conference held in Beirut (1970-71). These and other details find mention in Prof Ali’s book ‘Afro-Asian Poetry that Changed the World’, scheduled for a spring 2024 release.

‘Lotus’ was a trilingual quarterly magazine published in Arabic, English and French – and then translated into numerous languages of formerly colonized countries.

“The writers of ‘Lotus’ as well as the journal itself had a huge cultural impact at the time, affecting tens of millions of people. This was the first time writers of Africa and Asia were able to talk to each other, across their vast continents, outside the prism of their colonial and imperial usurpers,” says Prof Ali, who is currently busy digitizing and archiving the magazine.

Not just Palestine, ‘Lotus’ also took a stand against the burning issues of the time: the Vietnam War, the struggle against British, French and Portuguese colonial outposts in Africa and Asia, and against the apartheid regimes of South Africa and Zimbabwe.

“The aim was to not simply provide a service for those studying Afro-Asian literature but to ‘bring the literature of our continents into the arena of world literature’ (Alex La Guma, Lotus No. 17, page 132-133),” says Prof Ali.

He also quotes Youssef El Sebai, the magazine’s first editor, who wanted Afro-Asian writing to transform the world and establish values which would make life more just and beautiful.

The writers

Some of the prominent writers who contributed to ‘Lotus’ included Youssef El Sebai, Abdel Aziz Sadek, Edward El Kharrat (Egypt), Mouloud Mammeri (Algeria), Mulk Raj Anand (India), Hiroshi Noma, (Japan), Dr Soheil Idriss (Lebanon), Sononym Udval (Mongolia), Faiz Ahmed Faiz (Pakistan), Mario De Andrade (Portuguese Colonies), Mohamed Soleinian (Sudan), Alex La Guma (South Africa), Anatoly Sofronov (USSR), Adonis (Lebanon) and Mahmoud Darwish (Palestine).

The magazine instituted the Lotus Prize and among its recipients were Pakistan’s Faiz Ahmed Faiz and India’s Harivansh Rai Bachchan (whose son Amitabh is a well-known actor). Translation bureaus were launched in many countries of the two continents – so that people could read each other’s works.

Sociologist Prof Neshat Quaiser, recalling the magazine, says, “Lotus was a literary forum of the Third World writers against the First World’s ideological, economic and literary domination. It was a kind of a think-tank of Afro-Asian progressive writers. It signified a movement of the Third World Periphery against the ideological and political hegemony of Metropolitan West.

“It brought together anti-colonial and anti-imperial writers, and more importantly progressive writers of all Indian languages. It influenced the literary writings in Indian languages, and introduced Indian readers to literary giants such as Pablo Neruda, Naazim Hikmat, Alex La Guma and Mahmoud Darwish.”

Resolution on Palestine

According to Prof Ali, at the third Afro-Asian Writers’ Conference held in Beirut (1970-71), the writers passed an 11-point resolution on Palestine. They considered “the Zionist movement as colonialist by nature, expansionist in its aims, racist in its structure, fascist in the means it is using”; “Israel as an imperialist base and a docile tool used for aggressive purposes against Arab states in order to delay their progress towards unity and socialism, and as a bridge-head which neo-colonialism relies on in order to maintain its influence over African and Asian states.” They also viewed “the aggressive Israeli presence in Palestine as artificial, usurping and demographically imperialist...”

The conference appealed to the Afro-Asian writers, and to all progressive writers of the world, to stand in the face of the wide cultural conspiracy launched by the Zionist movement through writers and to view the Israeli presence as a fascist and racist system, in terms of a setback to civilization directed against human progress.

The writers denounced “the heavy cultural siege laid by Israel on one quarter of a million Arabs living in occupied territory under a hateful racial oppression in their own land,” and hailed Palestinian Arab writers living in occupied Palestine under terrorist rule, for their valiant stand in defense of the rights of the Palestinian people to liberate their country.

The resolution also hailed Afro-Asian writers who had stood up to Zionist forces and their support to “the Palestine Liberation Organization which leads the struggle of the Palestinian Arab people to liberate Palestine and to regain their usurped homeland by any means.”

The 1979 issue

The magazine’s cover (issue No. 38/39 – 4/78-1/79) was designed by an 11-year-old Palestinian boy, Mustafa Hussein. There was a splash of colors – red, green, black and yellow. “Red means revolution; green means a fertile, generous country; yellow means the desert. Because the Palestinian people were driven to wander far from their cities and villages,” Mustafa explained in a note.

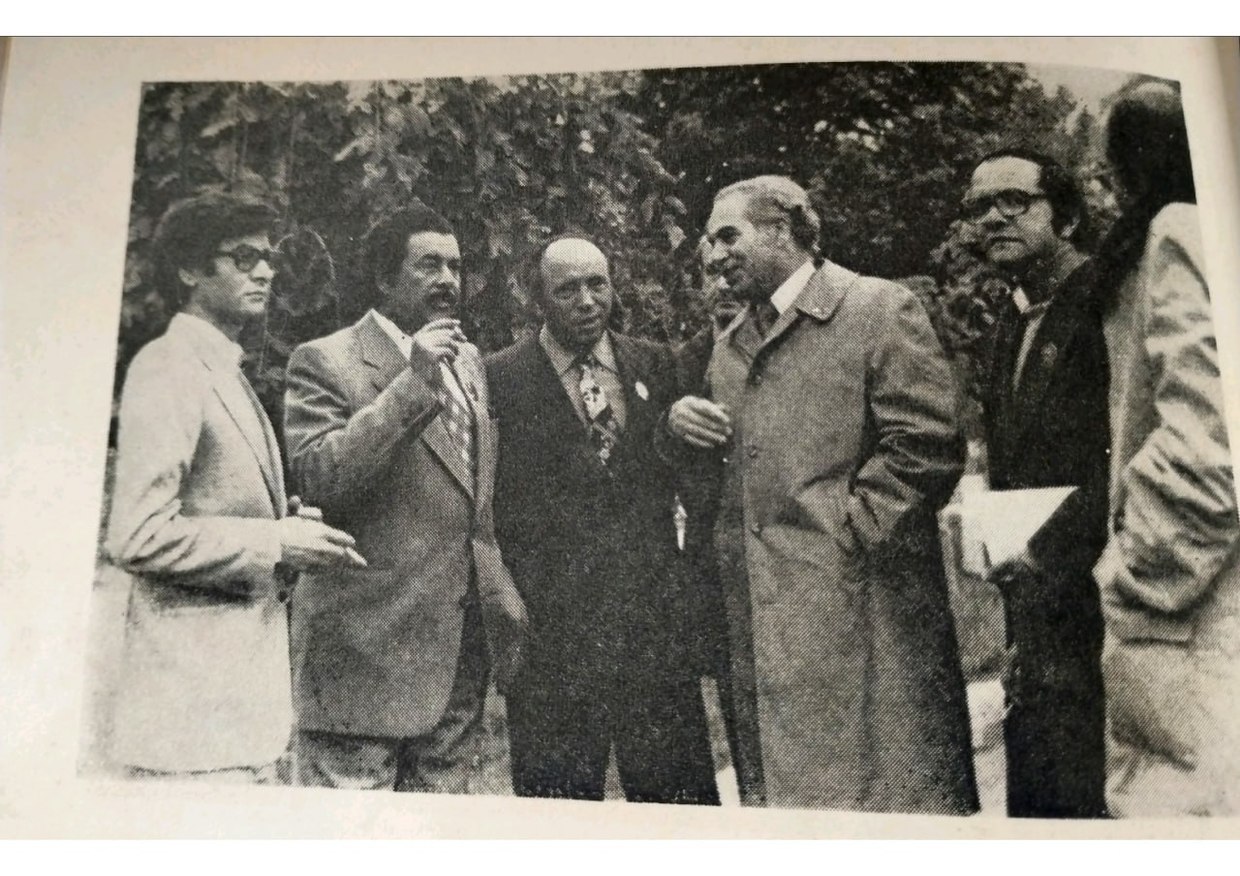

The 20th anniversary of the First Conference of Afro-Asian Writers (Tashkent, October 10-13, 1978) – which brought together prominent literary figures from more than 50 countries – featured in a commemorative issue. Among those who attended the meeting were Indian poet and writer Subhash Mukherjee, Faiz, and Darwish.

Mirza Ibragimov and Darwish highlighted problems of the Arab people at the conference. “The Palestine issue had become pivotal to the entire struggle in the Middle East, yet another manifestation of the great commitment to freedom fighting,” said Darwish.

In an essay, ‘The Road Passed, The Road to Pass’ Mukherjee quotes Faiz to describe the birth of the Afro-Asian Writers’ Movement: “Small springs, each flowing its own way, were to merge into a single stream.”

Mukherjee states that these writers saw it as their duty to awaken the conscience of the world, and goes on to quote South African writer Alex La Guma, “It might be that our individual heads have grown whiter...But in truth it is the enemy, imperialism, which has grown older...”

The Lotus project

In an article ‘The Road to Lotus: Faiz Ahmad Faiz’s Magazine Proposal to the Soviet Writers Union’, MJ Ernst and Rosen Djagalov delve into Faiz’s October 1963 proposal to the Soviet Union of Writers.

According to Ernst and Djagalov, though the magazine’s first issue came out in March 1968, plans had been in the making for at least a decade. The earliest proposal for such a publication dates back to the first inaugural 1958 Tashkent Congress of the Afro-Asian Writers Association.

They cite a 1964 note by the General Secretary of the Soviet Writers Union (signed by Alexey Surkov and G Markov) to the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union to launch the literary magazine:

“In light of the anti-communist and anti-Soviet campaigns conducted by imperialist circles through different cultural and press organizations (such as Encounter in England, as well as Thought and Current in India), the question of the founding of a progressive, multilingual literary and political magazine somewhere in Asia or Africa has become particularly pressing.”

The note further states that the importance of such a journal was also reinforced by the activities of the Chinese schismatics, who financed different foreign journals such as Eastern Horizon in Hong Kong and Revolution in Africa, Asia, and Latin America, to pursue their interests.

“These magazines systematically publish writers and journalists from various countries, who criticize the policies of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union and other fraternal parties,” the note read.

The general secretary suggested that one of the founders of such a magazine and possibly its editor could be the “famous Pakistani Communist poet, Lenin Peace Prize laureate” Faiz Ahmad Faiz.

Faiz Ahmed Faiz’s proposal

Faiz visited Algeria, the United Arab Republic, and Lebanon, where he examined the practical possibilities of publishing and distributing such a magazine, and suggested Beirut as a good base to launch the magazine due to its geographical location and absence of serious censorship and currency restrictions.

In his proposal, Faiz wrote that over the past few years “the nations of the capitalist camp – the United States in particular – have waged a continuous, systematic, well-organized and generously financed ideological campaign, which has been particularly powerful in the countries of Asia and Africa.”

Faiz proposed to bring out the first issue in the spring of 1964 and the second in autumn, and to convert the magazine into a quarterly by 1965.

Based on Faiz’s proposal, the general secretary recommended “an initial investment of around 10,000 GBP,” Ernst and Djagalov say.

The last edition

In another article on ‘Lotus Magazine: Soviet-Supported Afro-Asian Literary Transnationalism (1969–1970)’ Djagalov writes that the magazine was a result of the Cold War between the two superpowers, and its attempt to assert its influence on the Third World.

Djagalov read transcripts of the 1969 and 1970 Lotus editorial board meetings in Moscow and Cairo, respectively, and wrote: “These conversations show the magazine slipping from Soviet cultural bureaucrats’ grasp, as Cairo-based editors Yusuf al-Sibai and colleagues protect their local priorities and a wide range of African and Asian writers vigorously debate the identity and purpose of this Soviet-funded magazine published in English, French, and Arabic, but never Russian.”

Prof Quaiser echoes the same sentiment, “It wasn’t just the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 and a lack of funding that led to the magazine’s downfall. There were other factors too.”

Whatever may be the reason for the closure of this magazine, one can’t help but wonder if the power of writing could have saved thousands of lives in Israel’s ongoing war on Gaza.