Restless Buddhists: Activists sleep under night skies in the frozen Himalayas in a bid to protect their ‘fragile moonscape’

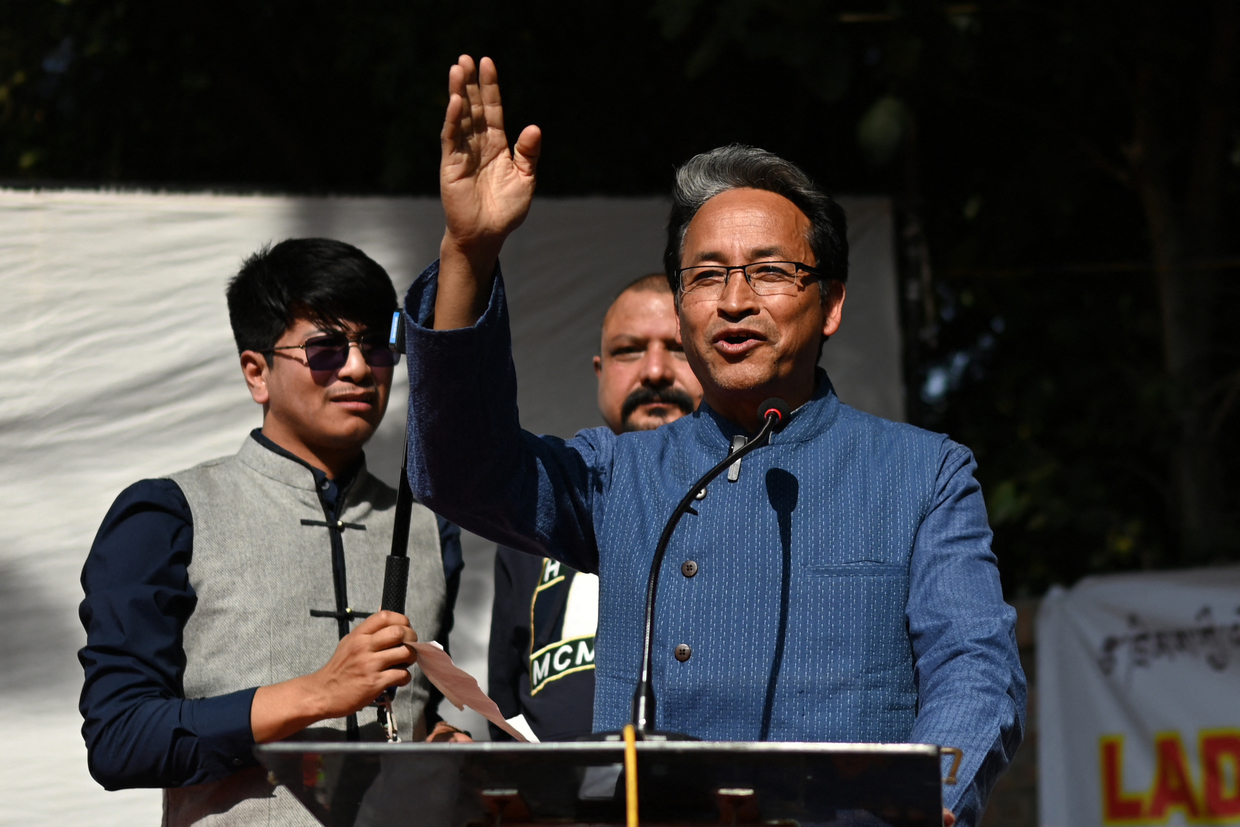

For 16 days climate activist Sonam Wangchuk has been sleeping, in sub-zero temperatures, under the open sky in India’s northernmost frontier Ladakh region.

He is on a 21-day ‘fast unto death’ to demand legal protection for his people’s land, jobs, self-governance and their climate. Wangchuk and his supporters want the people of Ladakh to be included under the Sixth Schedule of the Constitution of India, which provides greater autonomy to tribal areas (as in some of India’s northeastern states).

“My protest is in solidarity with the glaciers of Ladakh” Wangchuk, an engineer and innovator, says. He gained recognition after the Bollywood movie ‘Three Idiots’, which not only inspired him, but gained a place in mainstream India’s consciousness.

BEGINNING OF DAY 16 OF #CLIMATEFAST120 people sleeping outdoors under clear skies. Temperature: - 8 °C 16 days of just water n salts is finally taking a toll. Feeling quite week. But I can still drag for another 25 days n perhaps will.I'm sure our path of truth will win… pic.twitter.com/jsTFlvgD4c

— Sonam Wangchuk (@Wangchuk66) March 21, 2024

This high-altitude, mountainous land is wedged between China and Pakistan; on the Western side is the world’s highest battlefield, the Siachen Glacier, where Indian and Pakistani troops have been in a face-off since 1984. In 1999, the two countries went to war in Ladakh’s Kargil district.

On the Eastern side is the Line of Actual Control with China where, in the Galwan Valley in June 2020, a clash (without bullets) claimed the lives of both Indian and Chinese soldiers, deepening the prolonged tension between the two nuclear-armed neighbors.

Ladakh’s sparse but picturesque landscape gives it the title of ‘cold desert’; its town Dras is called the second coldest inhabited place on Earth. Temperatures routinely dip to -30 C in the winter. With rugged mountains, deep valleys, and high plateaus, Ladakh is also home to many big and small glaciers. Tourism flourishes in peak summer, when tourists outnumber the locals.

Constitutional Conundrum

In such a strategically important border region, New Delhi faces a protest that Wangchuk says he is committed to seeing through. It stems from a decision taken by the government of India in August 2019; prior to that Ladakh had been a part of the northern state of Jammu and Kashmir, which enjoyed a special constitutional status (known as Article 370), which provided exclusive citizenship and land rights to permanent residents.

The ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) has from its inception believed the provision was discriminatory towards outsiders. Separating Ladakh administratively from Jammu and Kashmir fulfilled a long-standing hope of Ladakhis, who erupted in jubilation. At the time, Wangchuk became one of the BJP’s most vocal supporters.

Both Ladakh and Jammu and Kashmir are now directly ruled by New Delhi under what is called ‘President’s Rule’ – a provision envisaged as temporary until state and parliamentary elections take place (they have not, since 2019).

Subsequent to the constitutional change, the National Commission for Scheduled Tribes wrote to the government recommending that Ladakh’s eight tribes – the Balti, the Beda, the Bot/Boto, the Brokpa/Dropka/Dard/Shin, the Changpa, the Garra, the Mon, and the Purigpa – be included under the Sixth Schedule for the democratic devolution of power, protection of agrarian land, promotion of their distinct culture, and funds for development. Ladakh’s 300,000 population is 97% tribal, spread across the two districts of Buddhist-majority Leh and Muslim-majority Kargil.

This recommended constitutional protection was not acted upon. Instead, non-locals are now allowed to buy land and settle in Ladakh.

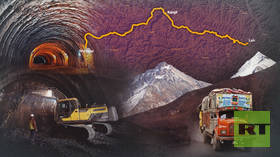

Over the past four years, the government has undertaken significant initiatives for economic development including building massive roads. At least ten agreements have been signed with outside companies to harness the region’s natural resources.

These include an agreement with the Oil and Natural Gas Corporation (ONGC) to establish India’s first geothermal power plant in Ladakh’s Puga Valley, renowned for natural hot springs.

Another is with the National Thermal Power Corporation (NTPC) to establish India’s inaugural green hydrogen unit in Ladakh. This will facilitate five hydrogen-fueled buses in Leh, for sustainable transportation solutions.

Seven hydropower projects along the Indus River and its tributaries have also been proposed. The Ladakh Power Development Department (LPDD) has sought permission to clear over 150 hectares of forest land for electricity transmission lines.

All these initiatives come with environmental concerns for locals who are resisting external investment in the ecologically fragile region. They fear that the sparsely-populated area cannot handle the rush of outsiders or the proposed development projects.

Though Wangchuk’s protest is a fortnight old, this is the third round of protests in Ladakh. The first major action was in January and February 2023, and Wangchuk did a seven-day hunger fast last June. “It is like the region is under permanent President’s rule,” he told RT.

From Jubilation to Discontent

Ladakh’s jubilation has turned into discontent. Residents blame the central government for forgetting its promise of ‘tribal status’ to the region. “The government has repeatedly promised that it will provide constitutional safeguards to Ladakh but it has not been done,” says Wangchuk.

To put their collective demand before the government, two civil society groups the Leh Apex Body (LAB), representing the Buddhist-majority Leh district, and the Kargil Democratic Alliance (KAD), representing the Muslim-majority Kargil district, have repeatedly met the government in New Delhi, putting forth demands including full statehood for Ladakh, inclusion in the Sixth Schedule, job reservations for locals, and a parliamentary constituency for each district (at the moment, both districts comprise a single constituency).

The last such meeting was on March 4. In a statement, the government said that Home Minister Amit Shah “assured the delegation that under the leadership of Prime Minister Narendra Modi, the government of India is committed to provide necessary Constitutional safeguards to Ladakh”. According to the Ladakhis, however, the meeting yielded no results.

The region witnessed the biggest street protest in memory on February 3, when thousands gathered at the Polo Ground in Leh (Ladakh’s administrative headquarter), drawing attention to a political upheaval brewing within.

Dechen, a 27-year-old student from Leh, has been actively supporting the protest, and says her people have a distinct culture and identity that needs protection.

“Ladakh is a fragile ecosystem with unique biodiversity. Increased development can lead to environmental degradation and strain on natural resources,” Dechen says, adding that a rapid influx of outsiders can create economic disparities, choke opportunities for locals, and lead to their marginalization.

“The influx of outsiders, particularly if they outnumber residents or impose their cultural norms, can threaten the preservation of Ladakhi culture,” she adds.

Strategic development on a moonscape

Due to the strategic threats, India has been building infrastructure projects at a breakneck pace. “Ladakh today is facing a two-front insecurity challenge,” researcher Stanzin Lhaskyabs explains.

Yet at the same time, Wangchuk fears that the infrastructure development is bringing in multiple private projects that the locals have resisted, fearing that more people or industry will benefit no one.

“We are talking about a moonscape,” Wangchuk says. “Ladakh is fragile and can only hold this many people.”

But locals also say that unemployment has also grown, and youngsters are desperate for jobs. “There is a lot of frustration among the youth,” Jigmat Paljor, the coordinator of the Leh Apex Body, says. “There is an unemployment crisis.”

The Ladakhis want more jobs, but they don’t want an unchecked influx of outsiders and businesses – a paradox that could be resolved by political representation. But there has been no election since Ladakh was part of Jammu and Kashmir, and New Delhi is yet to decide if Ladakh’s sole parliamentary seat will be included in next month’s general election.

“We have been disempowered and have no say on important policies being implemented in the region,” said Sadiq Ahmad, 30, a resident of Kargil.

At the March 4 meeting, however, Home Minister Amit Shah also assured the Ladakh delegation that a “high-powered committee should continue to engage on issues such as measures to protect the region’s unique culture and language, protection of land and employment, inclusive development and employment generation,” according to a ministry statement.