Space Cowboys: How India plans to conquer the final frontier

Her shock and awe was clear as Elizabeth Rani, 48, spoke of the sonic boom and the orange-red flames streaking across the sky. She had just witnessed – from her hilltop shack at Manapad, where she feeds tourists spicy fish curry, fish fry and other seafood snacks – the flight of a Rohini-RH 200 sounding rocket, a 12-foot vehicle with instruments to probe the local meteorology.

The rocket had blasted off from Kulasai, around 5km from Manapad, a fishing hamlet with about 8,000 residents and dotted with a couple of ancient churches, in Thoothukudi district, the ‘deep south’ of the southern Indian state of Tamil Nadu.

The liftoff’s significance was in trumpeting India’s second spaceport at Kulasai on the east coast, about 770km south of India’s Cape Canaveral, where the Satish Dhawan Space Center (SDSC, which is also popularly known as Sriharikota Range) – the primary spaceport of the Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO) – is located.

Earlier that day, on February 28, 2024, Prime Minister Narendra Modi had remotely unveiled the foundation stone for the new launch complex.

The new spaceport, to be completed in two years for Rs 9.86 billion ($116 million) across about 2,300 acres, constitutes an intrinsic component of India’s ambitious agenda to become the new superpower in space through a whole gamut of initiatives.

These include: a new genre of rockets, satellites, and scientific missions to study different planets, distant galaxies and blackholes; a touchdown on Mars; a made-in-India space station by 2028; the landing of an Indian crew on the Moon by 2040; a search for exoplanets, or planets similar to the Earth; and the opportunity for burgeoning space-tech start-ups as well as micro, small and medium enterprises to garner a slice of the multibillion-dollar satellite manufacture and launch vehicle markets.

These initiatives, however, are tempered by the fact that they will not help India catch up with its neighbor and adversary, China. On May 3, Beijing launched its second lunar soil-return robotic mission, Chang’e 6, with instruments from France, Italy, Sweden, and Pakistan. The first one, Chang’e 4, journeyed to the Moon and returned with about 1.7kg of lunar soil from the far side.

This international robotic mission has provided Pakistan an opportunity to launch its first lunar probe. The others in this mission are members of the European Space Agency (ESA). This complicated robotic mission, planned to return with 2kg of soil from the far side of the Moon, will help understand the early history of the solar system and the Earth’s natural satellite.

China also has an ambitious project to land a crew on the Moon by 2030 – a decade ahead of India’s plan.

Nonetheless, India is pushing ahead in the global market for small satellites that experts estimate will touch $13.7 billion by 2030, up from $3.2 billion in 2020. With a supportive ecosystem – including state-of-the-art infrastructure proposed for the design and production of small satellites near the launch facility at Kulasai – the Small Satellite Launch Vehicle (SSLV) is likely to ride into the skies with two small, medium or nanosatellites launches at least twice a month, complementing the launch activities at Sriharikota space center.

(ISRO has launched 432 satellites, including micro and nano satellites, belonging to 34 countries so far.)

Academia and researchers in government organizations, institutions and universities have been invited to participate in multi-disciplinary scientific investigations into factors driving climate change and extreme weather conditions. To add human capital to support its programmes, ISRO has launched an online training session, Space Science and Technology Awareness Training (START), for undergraduate and postgraduate students.

Such a multi-pronged approach mirrors the achievements by Indian space scientists in recent years: the world’s largest constellation of remote sensing satellites, the first space-faring nation to enter the Martian orbit on its first attempt, and the fourth nation to achieve a soft landing on the Moon. All of them were accomplished on shoe-string budgets.

Two critical factors dovetail with these efforts to be a space powerhouse: a pole position in the changing geopolitical scenario and expectations India will emerge as the world’s third largest economy with a GDP of $5 trillion in the next three years.

Alur Seelin Kiran Kumar, member of the Indian Space Commission and former ISRO chairman, summed up the new spaceport: “It’s the beginning of a whole range of activities, not the end itself,” he told RT.

“Activities (in the realm of space) will be expanded so that more Indians can participate, and satellites launched from different locations. To boost our economy, the private sector must play a significant role. ISRO will encourage the participation of the private sector in the manufacture of satellites and launch vehicles,” he said.

His former colleague and retired senior adviser to the ISRO chairman, Dr Tapan Misra, who is now an entrepreneur and founder of SISIR Radar, explained how the new spaceport will support the launch of small satellites and make every mission more economical.

“Our rockets [blasting off from SDSC] had to fly southeast and turn southwards later to avoid flying over Sri Lanka. This maneuver meant additional fuel at the cost of the weight of each payload (satellite). The new spaceport will help avoid such a maneuver for rockets heading southwards, saving the expenditure on additional fuel to make every flight more economical,” Dr Misra said.

“We can grab a bigger slice of the multibillion-dollar international market with such economic launches. With the conducive ecosystem, spacetech start-ups can develop hardware for indigenous civilian and military applications and export the hardware and satellites (to support remote sensing and navigational activities) over the next five to ten years,” he added.

Kiran Kumar, who also helms the advisory committee on space sciences at ISRO, added: “We will take space sciences to the next level to get contemporary in scientific investigations through several new missions, including follow-up visits to Mars and Moon, a probe to Venus, another to focus on exoplanets (planets similar to Earth), a follow-up on Astrosat for studies on distant galaxies. It will be our endeavor to be on par with leading space-faring nations.”

During his recent visit to Bengaluru, Prof Anil Bhardwaj, director of the Physical Research Laboratory (PRL), Ahmedabad, discussed a new family of launch vehicles and advanced modules for probing Mars and the Moon.

“One of the questions we are addressing is a probe that can heli-hop on Martian soil,” he said.

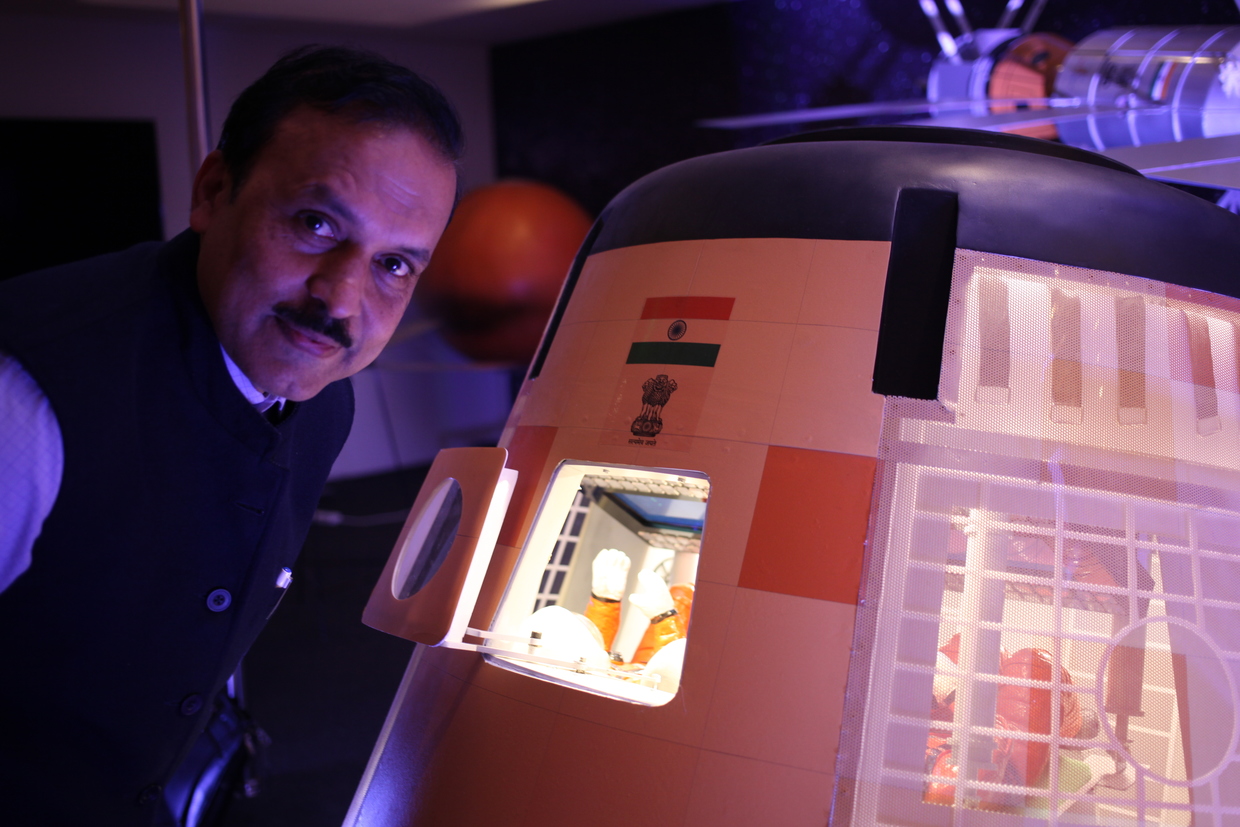

Space scientists are tight-lipped about the new genre of rockets. Details of the three-stage, heavy-lift rocket, LMV-3, to ferry Indian astronauts into space as part of ‘Gaganyaan’, however, are available in public domain. Ditto with ‘Pushpak’, the desi variant (and smaller version) of the US-NASA space shuttle. On March 22, a prototype made a successful autonomous touch down after its release from a height of 4.5 km.

Meanwhile, space entrepreneurs, or ‘spacepreneurs’, are ecstatic about the new spaceport and the new guidelines for foreign direct investment (FDI) in the spacetech sector. They nurse ambitions of a meteoric rise like Elon Musk.

New government rules for the import of foreign exchange, notified on April 16, entail up to 100% FDI through the automatic approval route for the manufacture of components and systems or subsystems for satellites, ground segment and user segment. Earlier, FDI was permitted only by government approval to establish and operate satellites.

The new rules also allow up to 74% under the automatic route for satellite manufacturing and operations, ground segment and user segment along with satellite data products, and up to 49% under the automatic route for launch vehicles and associated systems or subsystems and creation of spaceports for launching or receiving satellites.

These spacetech start-ups are aiming high, literally – from private space stations to a new class of sturdy but lightweight rockets, new satellite propulsion systems, and even systems that could sweep outer space clean to combat the menace of space debris.

“The decision to construct a new spaceport is aligned with ISRO’s broader vision of promoting extensive participation by private partners,” said Hari Shankar R L, co-founder and CEO of SPACETUG, a start-up based in Chennai. “It encourages technology sharing and the development of competitive satellite and launch services that can attract global customers.”

He feels it could significantly impact India’s presence in the international arena, potentially shifting market dynamics by providing more cost-effective and reliable launch options. “And by opening up to 100% FDI, India is laying the groundwork for an ecosystem that supports a thriving space economy, fostering entrepreneurship and creating high-tech job opportunities,” he said.

According to Apurwa Masook, founder & CEO of SpaceFields, a start-up incubated at the Indian Institute of Science, Bengaluru, – which made headlines when it raised Rs 65 million ($778,700) in seed money last month – the new spaceport’s proximity to the Equator will make the launch of satellites more affordable.

“The amount spent on fuel will decrease, providing start-ups an advantage. Even a small margin is welcome in the space industry,” he told RT. “Besides, the decision on 100% FDI will turn India into a favorite destination for investments and catalyze the development of advanced technologies and new systems quickly.”

Spacepreneur Pralhad Kulkarni, chairman of the Biocosmic Innovations Pvt Ltd, and astrobiologist, said: “Global investors understand that it is the right time to be in India because of the potential of space tech industries and a proven record in the launch of satellites by ISRO.”

A bit of politics is at play with Tamil Nadu’s state government launching a Space Industrial and Propellants Park across 2,000 acres, neighboring the new spaceport in Thoothukudi district. The park aims to create a vibrant ecosystem for space industry players in the backyard of Chief Minister MK Stalin’s sister, Kanimozi Karunanidhi’s parliamentary constituency.

“The new spaceport will be the nucleus around which these industries will develop. Some West Asian nations have already evinced interest in investing here,” Dr Mylswamy Annadurai, known as India’s ‘Moon Man’ and vice chairman of Tamil Nadu’s Aerospace Committee, told RT.

Dr Sargunaraj Christopher, former chairman of the Defense Research and Development Organization (DRDO) and now at the helm of the Aerospace Industry Development Association of Tamil Nadu (AIDAT), said the proposed defense corridor could extend southwards from Coimbatore (known as Tamil Nadu’s “Manchester”) to become part of the hub of activities near the spaceport, between the pilgrim centers of Rameswaram and Kanyakumari, the southernmost tip of India.

The only ones slightly wary of the Indian space industry’s new trajectory are Elizabeth Rani and local fishermen like George Fernandes, 30, and Santosh, 45, who fear rocket launches will squeeze their paltry earnings.

“We’ve heard from local officials that we won’t be allowed to venture into the sea [Bay of Bengal] for three days before every launch, which means we won’t be able to earn as much as we do now,” bemoaned George Fernandes, who has been riding the waves along with his father Francis Fernandes in their fishing boat for two decades.