When Hem Chandra Pande, a retired professor of Russian at India’s prestigious Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU), enrolled in a diploma course to learn the language at Delhi University in 1961, it was very popular. Many were trying to master it.

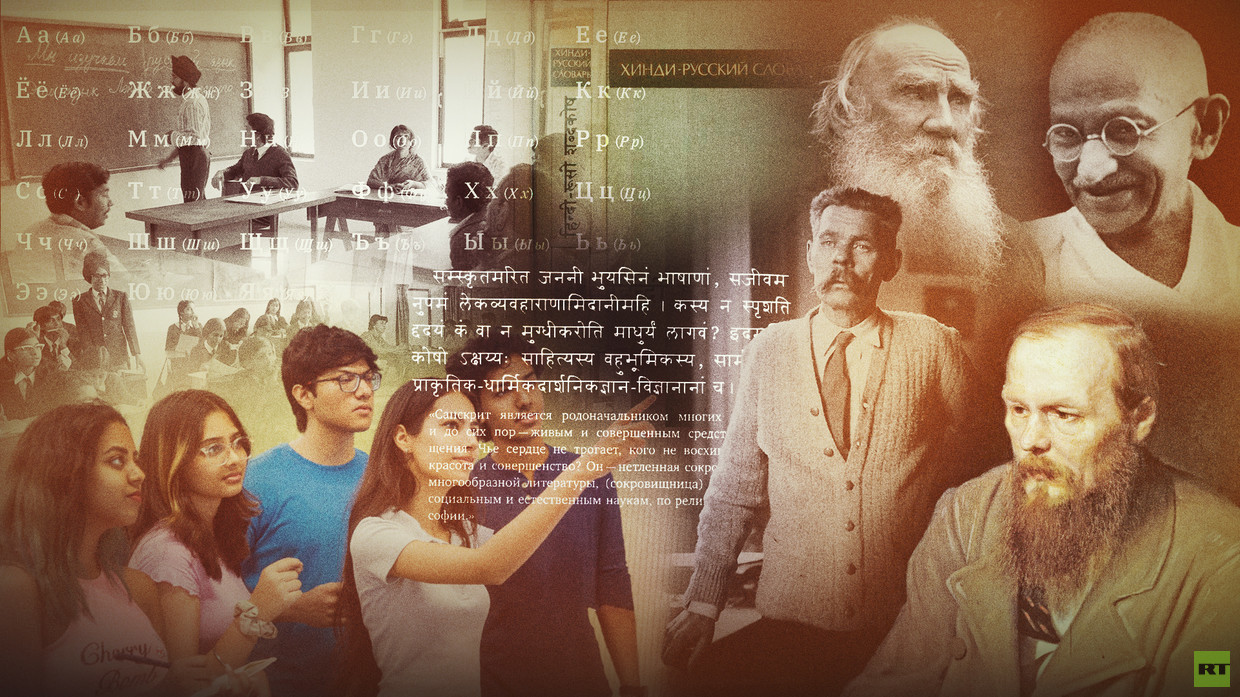

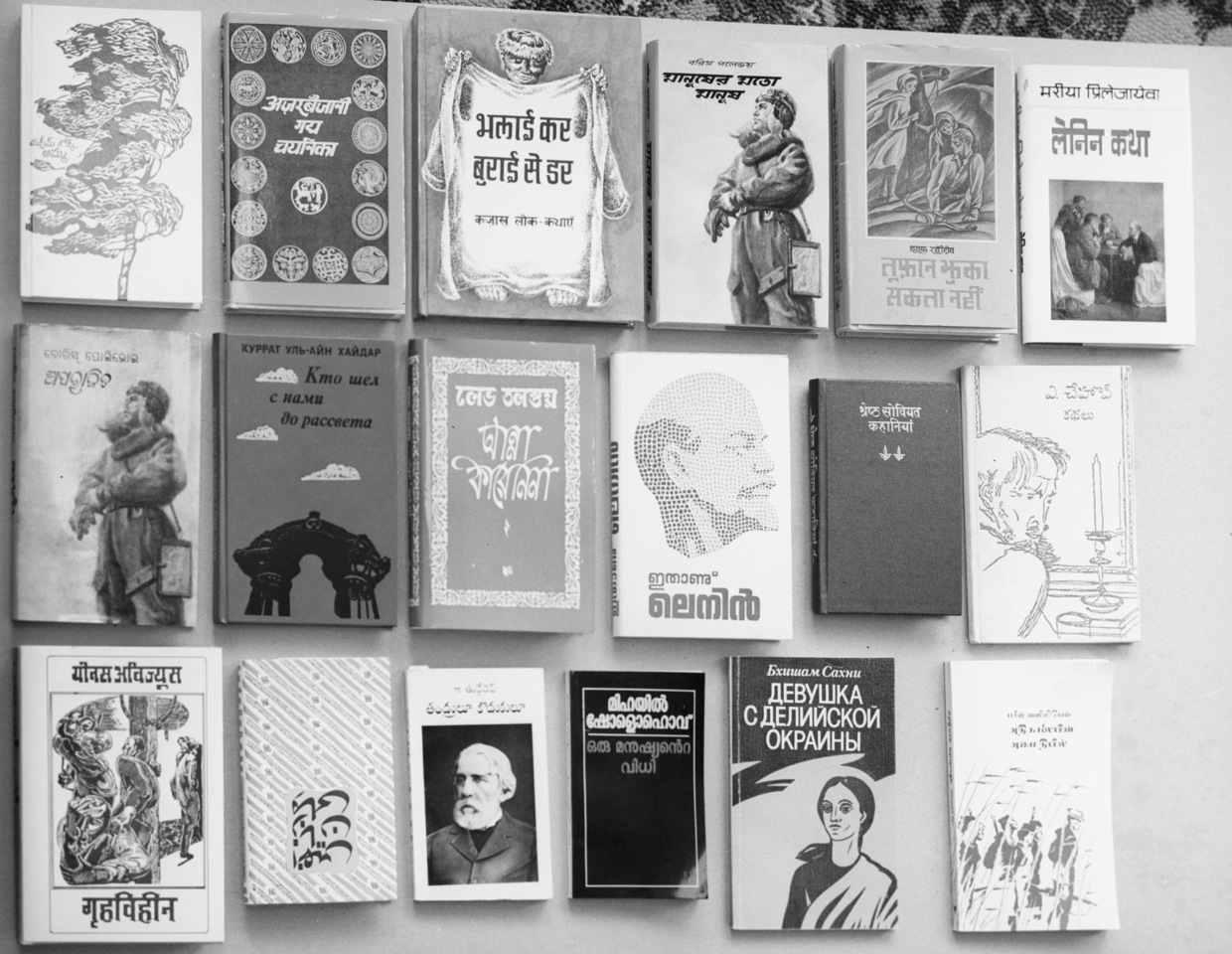

As with many others, what triggered his interest in Russian were the literary classics that were particularly popular. “The books’ translations into English, Hindi and other Indian languages had superior production values,” he told RT in a telephone interview. “The print, the paper, the visuals, the low pricing – it was these books that instilled the habit of reading among Indians.”

Following the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991, the circulation of these Russian magazines and classics dried up, as did the lines to learn Russian.

Russian Language Teaching in India

Delhi University was the first in India to start teaching Russian, in 1946. Allahabad University (in the northern state of Uttar Pradesh) did so in 1947, followed by Osmania University (in the southern city of Hyderabad) in 1958, and the University of Poona (in West India’s Maharashtra) in 1964.

“The real boost to Russian language teaching came on October 27, 1965, with the signing of the Indo-Russian agreement to set up an Institute of Russian Studies in New Delhi,” Prof. Vinay Totawar, former Dean of the School of Russian Studies at the English and Foreign Languages University in Hyderabad, wrote in an article, ‘Galvanizing Russian language teaching in India’.

Following this pact, Russian language courses were upgraded as an independent subject. On November 14, 1965, the Institute of Russian Studies was established by India’s education ministry. It was absorbed into JNU in 1969 and rechristened as the Centre of Russian Studies, becoming part of the School of Languages, Literature and Cultural Studies.

Professor Totawar said the explosion in such courses across India from the 1960s through the 1980s was due to the demand for language experts to cope with the increasing scientific and technical cooperation between India and Russia.

There was also an active cultural exchange of Indian and Russian language teachers, and by the 1980s, about 30 universities in India were teaching Russian. By the late 1980s, there were more than 400 students getting a master's degree in the subject, about 200 getting a bachelor’s, and about 30 PhDs and MPhils, Professor Totawar said.

Just as Russian language teaching peaked in the field of science and technology, in the early 1990s it “suffered a slump,” the professor said.

“Interest in Russian declined,” according to Professor Tomar. “There were several reasons: political as well as economic. The disintegration of the erstwhile USSR and the lack of Russian support in providing teaching material. This lull in teaching Russian continued for about two decades and its quality. Few students chose to study Russian.”

Katherine Foshko in her research paper ‘Re-energising the India-Russia Relationship Opportunities and Challenges for the 21st Century’ (published in September 2011) described the Russian language study situation in India as “deplorable.”

“The Russian Embassy in India estimates that 40 colleges teach Russian across India (remarkably, only one in Mumbai); others have closed their programs, and the remaining ones face the problem of a lack of native speakers and new educational material,” Foshko found. “Courses generally attract only a few dozen students (from 20 at the University of Madras to 150 at Jawaharlal Nehru University in Delhi) and all have a high rate of attrition.”

Renewed Interest in the Russian Language

However, that is changing. Russian is no longer the last choice for foreign language learners.

There is a renewed interest, according to Professor Pande. “I get an occasional call to teach Russian to someone or to buy textbooks that I wrote (Russian for Indians, Russian Exercises for Indian Students and Advanced Russian),” he said. “This could be because Russia’s ties with India have deepened in the recent past and a lot of students are going there to study.”

Professor Sonu Saini, who teaches Russian at JNU, agreed: “The community of Russian language learners is growing in India. The rapid growth in bilateral ties, trade and cultural exchanges has created a demand for Russian experts. Earlier, when India held the chair of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) there was an acute shortage of Russian language experts.”

“After the fall of the USSR, the practice of translation almost ceased due to a lack of support from both governments,” Professor Saini said. According to him, the members of the Association of Translators-Interpreters of Indian Rusists are trying to bring back that level of exchange of literature through translations.

“The renewed interest among Indian readers may soon surpass the past popularity of Russian classics and contemporary writings,” he asserted.

“The recent visit of Prime Minister Narendra Modi to Russia and his meeting with President Vladimir Putin, the geopolitical scenario, the pace of the development of cordial relations, increase in trade, exchanges in culture, emerging BRICS and SCO collaborations are the reasons for people’s renewed interest,” Professor Saini explained in an email.

However, without government support on both sides, this is an uphill task. According to the professor, at present some organizations support the translation of Russian literature into Indian languages, such as the Institute of Translation in Russia, but more support is required to reach “earlier levels.”

“We are trying to collaborate with universities and organizations to promote Russian language and literature in India and Indian languages and literature in Russia,” Professor Saini said. “We are helping young Russian and Hindi language experts in all possible ways. We believe that India and Russia are the major economies of the future and are trusted friends forever – ‘Hindi-Russi-bhai-bhai’ (Indian-Russian brotherhood).”

All told, around 350 students are currently enrolled in the BA, MA and PhD programs at JNU’s Centre of Russian Studies. Meanwhile, new Russian courses are being introduced by private universities, colleges, institutions and schools, experts note. For instance, Russian courses have been introduced at a private school in Faridabad (a Delhi suburb) and a private university in Assam, a state in Northeast India.

Apps to learn Russian

Professor Saini is going the extra mile: he and his colleagues Zeev Fraiman and Elena Smirnova have developed three Android apps for learning Russian: ‘Play and Learn’ where one can learn the language through games; ‘Zoshchenko in Translation’ which includes 92 stories by Mikhail Zoshchenko, with text and audio in both Russian and Hindi; and ‘Phrasebook in Russian-English-Hindi’ based on a book by Professor Abhai Maurya.

Professor Saini felt technology in teaching a language was the need of the hour. “Today’s students use technology extensively,” he said. “We need innovative ways to turn their addiction into fruitful tools. There was a time when a mobile phone in class was considered a distraction, but turning it into a tool of teaching is appreciated. We use apps in class to practice and enhance what we have learned and it works well. Today thousands of educational apps are available, which help teachers. We are trying to develop more apps.”

Earlier, Professor Saini developed the first website of Russian studies in India, INRU, hosted on the Delhi University server. It was the first such initiative to help learners of Russian in India.

However, Professor Pande is a firm believer in traditional methods of teaching, such as a classroom setting. “You can learn a few things on the app but to master a language you need a systematic approach to learning,” he said.

The Silent Warriors

Professor Pande has compiled a Russian-Hindi dictionary but his most famous work is the translation of Russian Indologist Ivan Pavlovich Minaev’s Kumaoni folk tales into Hindi. Minaev visited Kumaon in 1875 and, during his stay, collected folk tales and legends. The translation consists of 48 folk tales and 22 legends.

Professor Pande’s last publication was the correspondence between Mahatma Gandhi and Leo Tolstoy. He started out as a Russian instructor at Hindustan Aeronautics Limited (HAL) and has written academic papers highlighting commonalities between Russian and Sanskrit. He cites several words which have common roots.

Professor Varyam Singh’s association with the Russian language began 55 years ago. He learnt Russian at JNU (where he taught during 1972-2013) and started translating poetry as a 22-year-old.

“I am from the first batch (1965) that graduated from JNU,” he told RT over the phone. “Before translating Russian poetry into Hindi, I learnt Hindi systematically to understand the art of translation.”

By 1975, his first collection of poetry was published, which included Alexander Blok’s poems to mark his birth centenary. He went on to translate 50 poems by Blok. Later, to mark Alexander Pushkin’s bicentenary, the Sahitya Akademi (India’s literary academy) commissioned him to translate the works of Pushkin and Fyodor Tyutchev.

“In 1986, the the Sahitya Akademi embarked on an ambitious project – translation of 20 volumes of 20th century Russian writers,” he said. “Unfortunately, due to the disintegration of the USSR, this plan was largely disrupted. Still, I got to choose and translate poets such as Alexander Blok and Joseph Brodsky.

“I did not care about how difficult the translation task would be. It should be philosophical in essence. Pushkin died early, at the age of 37, and I thought it was important to translate his works for Indian readers,” Prof Singh said.

He is nostalgic about the time when Pragati Prakashan in Moscow published translated works and sold them at low prices, especially children’s literature. He said it is tragic that not enough people now read Russian literature.

“Our first print orders are usually 1,100 copies, of which not even 500 are sold in our well-populated country,” he rued. “On the contrary, in a small country like Kyrgyzstan, 5,000 copies are published and sold. In India, no writer can financially survive by pursuing a career in writing.”

Professor Singh said the Sahitya Akademi still translates classical works by renowned Russian writers, but there is little awareness about contemporary writers.

Common Roots in Russian and Sanskrit

Prof Saini co-authored a paper, Affinity of Russian and Sanskrit: Mysterious Common Roots in Names of Relatives. This affinity was one of his first motivations to learn Russian.

“The Sanskrit and Russian languages are listed in the same language family group, i.e. Indo-European languages,” he said. “The grammatical structure of both is similar. Many words have common roots and they sound and mean similar in both languages.”

An example of sentences that sound and mean the same: ‘Tot vash dom’ (in Russian) and ‘Tat vas dham’ (in Sanskrit) both mean – “That is your house.”

Professor Saini reminded that Indian and Russian ties go beyond Afanasy Nikitin’s visit to India in 1471. “The proof of ancient cultural and trade ties was found in an excavation carried out near the Volga River, near Staraya Maina village, in the Ulyanovsk region in 2007,” Professor Saini said. “Many Indian artefacts such as coins, utensils and a statue of Lord Vishnu were excavated by Ulyanovsk State University, under the supervision of Professor Aleksandr Kozhevin. The artefacts are said to be from between the 8th and 10th century.”

The Indian Council of Social Science Research (ICSSR) is studying these artefacts, but “we need support for carbon dating and further excavations,” he said.

Taking Russian to Regions

Professor Charumati Ramdas became interested in Russian early in life, but only got an opportunity to learn the language in 1968, when ISCUS (theIndo-Soviet Cultural Society) launched classes in a big way.

“There was a generation that was known for its love for Russia,” recalled Professor Ramdas, who likes to translate Russian prose into Hindi and Marathi. Her favorite authors are Mikhail Bulgakov, Alexander Pushkin and Nikolai Gogol. She has translated modern authors including Roman Senchin, and has written about Victor Pelevin.

“I am not sure how many people are still reading Russian literature. There are collectors of books who occasionally get in touch with us but we are not sure if they are readers,” said Professor Ramdas, who retired from the English and Foreign Languages University (EFLU) in Hyderabad.

Her husband, Professor Ram Das Akella, who was also a professor of Russian at EFLU, translated celebrated writer Vyacheslav Kuprianov’s poems into Telugu and poet-lyricist Javed Akhtar’s ghazals into Russian, in a work which is due for publication.

“We translate out of our love for the Russian language,” said Professor Charumati Ramdas, suggesting translations are not profitable. “Unfortunately, India does not have a reading culture like Russia’s where people read even on trams.”

Anagha Bhat-Behere, an assistant professor in the Department of Foreign Languages at Savitribai Phule Pune University in Maharashtra, has also been translating Russian literature into Marathi.

“I am a consumer of Marathi literature and I am a part of the literary poly-system of Marathi,” Prof Bhat-Behere told RT. “I generally choose things which are not there in my literary polysystem or which I rarely come across in my language.”

She has been actively translating Dalit literature into Russian, apart from translating writer and social activist Anna Bhau Sathe’s My Journey to Russia into Russian and English. She also compiled the first of its kind tri-lingual Marathi-Russian-German dictionary, and founded a literary magazine.

Individually, she has published four books. Her translations include a collection of stories by Alexander Pushkin, Mikhail Saltykov-Schedrin, Fyodor Dostoevsky, Leo Tolstoy and Anton Chekhov, apart from translating Mikhail Lermontov, Victor Dragunsky and Andrei Gelasimov.

Likewise, Professor Megha Pansarev, who teaches Russian in Kolhapur, has also been translating Russian literature into Marathi. She translated Maxim Gorky’s IV-Act play The Lower Depths into Marathi. She focuses especially on children’s literature and has translated, among other works, The Singing Feather, a collection of short stories for children by Vasil Sukhomlynsky. Professor Pansarev has picked up several awards for her meticulous translations.

“Russian literature is popular among Marathi-speakers,” she said. “Besides, there are always serious readers in every language who value translated works. They may be few, but they matter, and the work must go on.”

“During the SCO summit in 2019, Prime Minister Modi announced that the 10 best works from various Indian languages will be translated into Russian as a symbol of cultural exchange,” Professor Saini said. “This task was assigned to us through the Sahitya Akademi.” According to him, about a dozen people translated these works, which were later gifted to the heads of state of SCO countries.

The need of the hour, Professor Saini asserted, is more such literary collaborations between India and Russia.

By Lamat R Hasan, an independent journalist based in New Delhi