Iraq’s first election since US pullout marked by death over political optimism

Any manifestation of democracy in Iraq was inevitably accompanied by bloodletting, as parliamentary elections closed on Wednesday. The day marked the first polls since US withdrawal amid unrelenting sectarian violence.

The turnout was predictably low, with only 30 percent out of the 22 million eligible attending, according to senior election commission member, Muqdad al-Shuraifi, in the final four hours of the poll.

In the current situation, even a successful attempt to bring people out to vote is no guarantee of quick results. The country is as fragmented politically as it is on the battlefield. Based on recent experience, even if voting demonstrates the success of democracy, a working coalition will take a great deal of time to establish. It took nine months to agree after the last election in 2010. That was when the United States was still around.

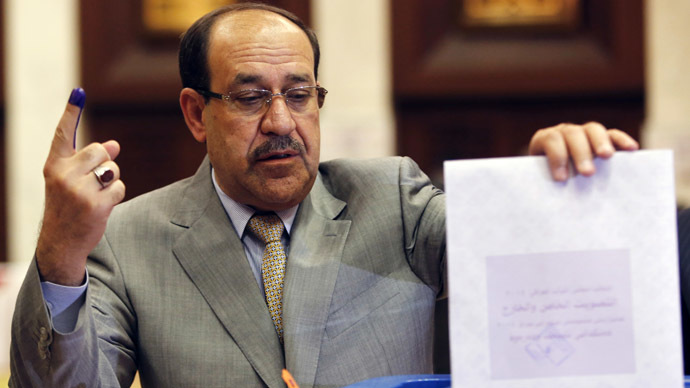

Iraqis were voting to elect a 328-seat parliament, with more than 9,000 candidates vying for spots, as the incumbent prime minister of eight years, Nouri al-Maliki will seek a third term. He was among the first to cast his vote today in the Green Zone, where the government is based. Addressing his nation, he was quoted by reporters as saying, “I call upon the Iraqi people to head in large numbers to the ballot boxes to send a message of deterrence and a slap to the face of terrorism.”

Today, in central Baghdad, security was ramped up, with voter searches performed before anyone was allowed inside polling stations. Police blocks and barbed wire line the capital’s streets. However, the day did not pass without violent incident and explosions scattered the country.

While the seemingly futile attempts at political order are made, chaos and disorder reign across the country. Voting in parts of the west has been canceled due to increased violence. In Fallujah, Sunni anti-government sentiment is marked by popular calls to rise up, showing just how difficult an inclusive political process is at this time.

Iraq’s security forces have not been successful after months of trying to take areas like the province of Anbar from the clutches of armed extremists. It has become a focal point of Sunni discontent.

Attacks have been taking place with a steady regularity - especially on electoral officials. Wednesday afternoon saw two roadside bombs go off in the north of the country, killing two staff from the electoral commission, further wounding two security officers, according to an army general. The attack took place to the north-west of the ethnically-mixed city of Kirkuk. Another two electoral stations were attacked with RPGs on the outskirts of Baghdad, as well as one in Mosul, 400km north of the capital - killing one. The total death toll from the Wednesday attacks stands at 11 at the time of publication.

A string of attacks took 24 lives across the country on Tuesday as well – the worst was a double bombing that killed 17 people in an outdoor market just outside Baghdad, in which most of the victims belonged to the Kurdish minority.

This follows Monday’s carnage, which claimed a further 50 in a wave of suicide attacks by militants disguised as security force members. Most of these targeted election campaigns.

2014 saw the deadliest April since 2008, and 4,000 lives have been lost since the start of this year alone, as the Shia government forces of al-Maliki engage a Sunni opposition. More than 400,000 have been displaced.

Al-Maliki’s party rose to prominence in 2006, just as violence started to really spiral out of control, with Sunni and Shia militants constantly striking each other’s populations. His party is expected to win the most seats on Wednesday, but is still unlikely to take a majority.

“Our victory is confirmed,” Reuters quoted him as saying, “but we are still talking about how big this victory will be.” This victory will depend on the PM’s ability to get a coalition together, and given the criticism he has received from nearly all ethnic and political denominations in the country, that is unlikely to happen, even amid an atmosphere of Al-Qaeda-inspired violence by groups like The Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL), which puts him in a unique position to be cast in the role of the defender of Shiites against extremist Sunni elements.

Despite the elections offering hope of a way forward, “the fear is that it’ll only fan the flames of discontent. The prime minster has been accused of being too authoritarian… of making sectarian divisions worse, instead of better,” RT’s Lucy Kafanov reports. “But the opposition is too fractured to mount a serious challenge.”

Since the violence of 2006, and up until 2008, the situation had somewhat calmed down, as the Americans reigned in the Sunni opposition, using their help to fight the more extreme, terrorist elements. But the Sunni-Shia animosity has since come back worse than ever, as Sunni Iraqis are complaining against discrimination by the government. That is aside from the already existing criticism of corruption and failures on all fronts, from infrastructure to health to education and the economy.

These are not only the first democratic elections since the US military pullout – they’re also the fourth since former leader Saddam Hussein’s ouster in 2003. It is becoming clear to some that any chances of stability, political or otherwise, have actually decreased since the time the start of the American occupation.

“If Iraq had gone through this transition to a perfect peaceful united government, they would still be faced with a very, very difficult legacy of complete destruction of the country’s infrastructure, the toxic legacy of depleted uranium and things like that. And there’s the psychological trauma of the whole population that was bombarded by the US military,” Iraq war veteran Mike Prysner told RT.

“Their lives are still dominated by the violence of war,” Prysner said.

Political scientist, Iraq War veteran and former US Marine Jake Diliberto believes this vote is not an indication of change, but a barely useful attempt to path up a sectarian hole that’s been left by the American occupation.

“Political elections going on in Iraq is going to bring two possible problems and two possible very good events: the first and biggest problem is sectarian tensions; the other problem is that Al-Qaeda could demonstrate itself as a powerful force by bombing election cycles, putting fear and intimidation into communities,” which could lead many to boycott the elections out of fear, Diliberto believes.

He sees the continuing spiral of brutality and government powerlessness as arising out of a combination of two things: “because of long-term traditional problems within the sectarian communities and because of the US inability to bring political results post-2003 invasion.”