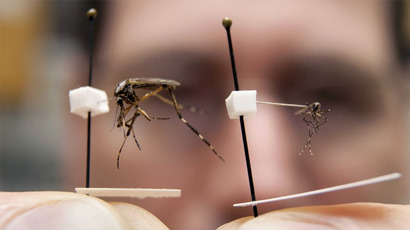

Genetically modified mosquitos could be used to fight malaria

Scientists have discovered a way to genetically modify mosquitos so their population will be reduced. The move is aimed at making a contribution towards eradicating malaria, though critics warn of the dangers of a changing ecosystem.

The technique, developed by scientists at Imperial College London, causes more than 95 percent of mosquito offspring to be born male. Over a period of six generations, the population will dramatically decrease as females disappear, according to the new research, which was published in Nature Communications on Tuesday.

The scientists inserted a DNA cutting enzyme called I-PpoI into mosquitos. The enzyme attaches itself to their X-chromosome during the male’s sperm-making process, which effectively shreds part of the chromosome’s DNA. As a result, almost no functioning sperm carries the X-chromosome.

“You have a short-term benefit because males don’t bite humans [and transmit malaria]. But in the long term you will eventually eradicate or substantially reduce mosquitos. This could make a substantial contribution to eradicating malaria, combined with other tools such as insecticides,” Andrea Crisanti, one of the authors behind the new research, told the Guardian.

The research is still in its early days, warned Dr. Roberto Galizi from the Department of Life Sciences at Imperial College London, adding that he hopes the new approach could ultimately lead to “a cheap and effective way to eliminate malaria from entire regions.”

Previous work carried out in 2008 took a similar approach but unintentionally resulted in sterile mosquitos and therefore the gene’s ability to spread was limited.

Malaria killed about 627,000 people in 2012, the vast majority of which were children in Africa, according the World Health Organization (WHO).

Current methods to combat the mosquito species responsible for the transmission of malaria (Anopheles gambiae) include insecticides and bed nets. However, the WHO has warned that malaria control is being threatened by insecticide resistant mosquitos and malaria parasites that are resistant to drugs. As a result, more than 3.4 billion people remain at risk of contracting the disease.

Nikolai Windbichler, a lead researcher at Imperial College’s Department of Life Sciences and a co-author of the paper, said the concept of distorting the sex of a pest’s population is an old one, more than 50 years old, but the technology to make it possible hasn't existed until now.

“What is most promising about our results is that they are self-sustaining. Once modified mosquitos are introduced, males will start to produce mainly sons, and their sons will do the same, so essentially the mosquitos carry out the work for us,” he said, as quoted by Imperial College News.

Dr. Luke Alphey – a specialist in vector-borne viral diseases at the Pirbright Institute in Berkshire, Southern England, who was not involved in the research – described it as an important step forward.

“The overall goal of this research program is even more ambitious – to develop a version of this genetic system that will spread itself through the target species, removing females and causing population crash or extinction as it goes,” he said.

But Dr. Helen Williams of Gene Watch UK, a not-for-profit group that is cautionary about GM mosquito research, warned that there may be unintentional consequences of removing a species from the ecosystem.

“We would want to ensure that the risks are properly considered before GM mosquitos are released into the environment. For example reducing the population of one mosquito species can increase the population of other mosquitos, so you can potentially make it worse,” she said.