‘Humdinger’: Swine flu virus which killed half-million modified to 'incurable'

A controversial flu researcher has modified the flu virus responsible for the 2009 pandemic to allow it evade the human immune system. His lab’s previous works include recreating the Spanish flu and making a deadly bird flu strain highly transmittable.

The yet-to-be-published research by Professor Yoshihiro Kawaoka and his team is meant to give scientists better ways to fight influenza outbreaks, but gives chills to some people in academia, who are fearful that accidental release of the strain would result in a global disaster, according to a report by the Independent.

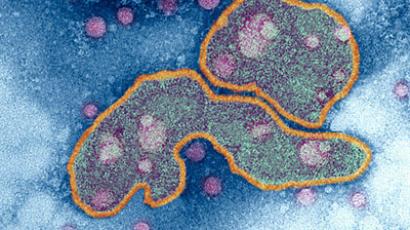

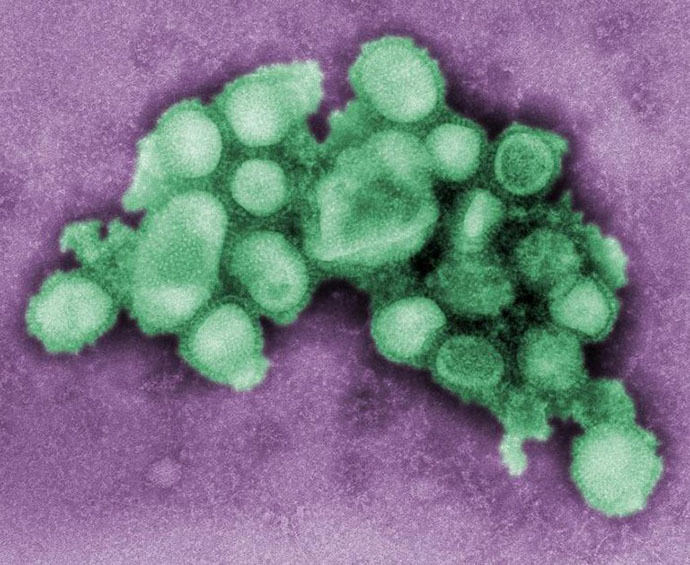

At his level-3 biosafety lab at Wisconsin University’s Institute for Influenza Virus Research in Madison, Kawaoka experimented with the H1N1 flu strain that was responsible for the pandemic in 2009, dubbed the swine flu pandemic by the media. The work resulted in a mutated strain that is able to evade the human antibodies, effectively rendering humans defenseless against the virus.

“He took the 2009 pandemic flu virus and selected out strains that were not neutralized by human antibodies. He repeated this several times until he got a real humdinger of a virus,” a scientist familiar with Kawaoka’s research told the British newspaper.

“He’s basically got a known pandemic strain that is now resistant to vaccination. Everything he did before was dangerous but this is even madder. This is the virus,” he added.

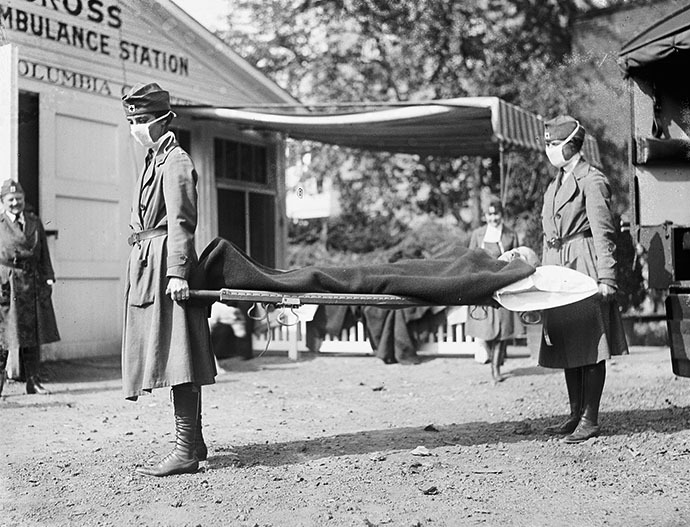

H1N1 flu had caused serious outbreaks and two recorded pandemics, the first being the notorious Spanish flu of 1918. Kawaoka’s newest work is partially derived from his experience in recreating the deadly strain.

The first H1N1 pandemic left between 50 and 100 million people dead, according to estimates. The 2009 pandemic death toll is debated, with some estimates putting the number as high as 560,000, most of them in Africa and Southeast Asia.

The professor assured the newspaper that the mutant virus is well under control in his lab and that making a strain that can beat human immune system will help epidemiologists be prepared for a contingency of a similar mutation occurring naturally.

“Through selection of immune escape viruses in the laboratory under appropriate containment conditions, we were able to identify the key regions [that] would enable 2009 H1N1 viruses to escape immunity,” he said in an email.

“Viruses in clinical isolates have been identified that have these same changes in the [viral protein]. This shows that escape viruses emerge in nature and laboratory studies like ours have relevance to what occurs in nature,” he added.

The research was approved by Wisconsin’s Institutional Biosafety Committee, although a minority of the 17-member board is critical of Kawaoka’s line of study. One such vocal critic at the committee is Thomas Jeffries, who argues that an accidental release of the virus from the safe lab is possible, citing the recent incident at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, which potentially exposed some 80 people to anthrax bacteria.

"I think we can sometimes fool ourselves into thinking we have more control over a situation in a laboratory than we do," he told Wisconsin State Journal last week. "Accidents do happen."

When The Independent approached Jeffries for comments on Kawaoka’s new research, he said he was not made aware of details of the study at the time the approval was given.

“What was present in the research protocols was a very brief outline or abstract of what he was actually doing…there were elements to it that bothered me,” Professor Jeffries said.

Rebecca Moritz, who is responsible for overseeing Wisconsin’s work at the institute, said it is needed to create new vaccines.

“The work is designed to identify potential circulating strains to guide the process of selecting strains used for the next vaccine…The committee found the biosafety containment procedures to be appropriate for conducting this research. I have no concerns about the biosafety of these experiments,” she said.

Kawaoka said he presented preliminary results of his research to the World Health Organization and they had been “well received.”

“We are confident our study will contribute to the field, particularly given the number of mutant viruses we generated and the sophisticated analysis applied,” he explained.

“There are risks in all research. However, there are ways to mitigate the risks. As for all the research on influenza viruses in my laboratory, this work is performed by experienced researchers under appropriate containment and with full review and prior approval by the [biosafety committee],” he added.

Flu virus strains are notorious for changing rapidly, with new strains emerging and causing seasonal flu epidemics. Scientists have to try and predict what kind of flu they would have to face each year and have a vaccine ready. When they succeed, an outbreak causes much less damage that it could have otherwise.

Research of ‘gain of function’ by viruses like the works of Kawaoka is focused on exploring how a virus can become deadlier and more transmittable or resistant to existing vaccines. Critics of such studies say they are too dangerous, both due to the risk of accidental or even deliberate release.

For instance some people in the academia called on Kawaoka to withhold parts of his research on H5N1 bird flu. Normally the virus is highly lethal, but does not transmit well, but a series of experiments with ferrets resulted in an easily transmittable strain. The experiments were simple enough for any person with expertise in microbiology to replicate, which critics said some group of would-be bioterrorists would eventually do.