‘Mysterious’ meteorite may shed light on explosion of life on Earth

Published 2 Jul, 2014 18:18 | Updated 3 Jul, 2014 05:51

Researchers have discovered a fossilized space rock that stands out against anything seen before. It may advance the understanding of the asteroid clash that triggered off the diversity boom of life on early Earth.

Most of the meteorites that have fallen to Earth and were found during a 20-year study originate from a huge asteroid that collided with a smaller one – or even a comet – millions of years ago. But before the latest finding by scientists in Sweden nothing was known about the mysterious “bullet” asteroid.

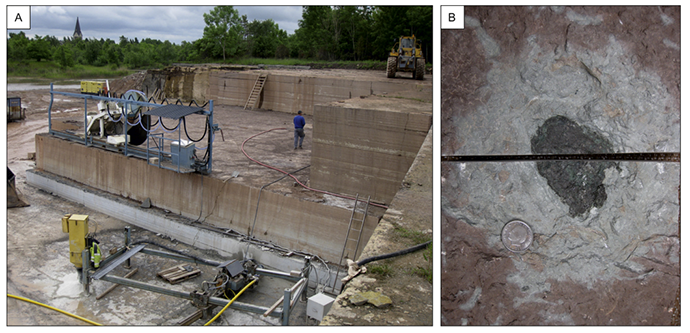

A study by a team of international researchers, prepared for print in the August edition of ‘Earth and Planetary Science Letters’ journal, tells the story of the exploration of a meteorite found in Thorsberg limestone quarry, west of Stockholm, in southern Sweden.

While previous finds have become "quite boring,"according to Birger Schmitz, lead author of the study, who has led the chondrite cataloging, the most recent discovery is “a very, very strange and unusual find.”

Three years ago, while taking part in the industrial process of mining white limestone, used for production of floor plates, for example, the scientists found a gray dissemination in the youngest quarried bed. It was a piece of the ancient wreckage.

Over 100 fossil meteorites have been found in the quarry since the start of the research in 1993. But most interest has centered on the so-called “Mysterious Object.”

"This can give you a ground truth for models for how the solar system may have evolved over time," said Gary Huss, a co-author of the meteorite study. "I think a lot of people have worried for some time that we don't really know what's going on in the asteroid belt."

About 85 percent of the meteorites raining down on Earth today are ordinary chondrites, and nearly half of those (45 percent) are so-called L-chondrites. Their features show that they are remains of a parent body that clashed with a smaller asteroid in a major space event that happened around 470 million years ago. What marks this breakup is the trace it left in our planet’s geology and biodiversity. Scientists say the destruction caused by the resultant meteor shower led to a burst of new species formation in the early part of the Ordovician period.

David Harper, a geologist at Durham University who did not participate in the study, pointed out that "the team may at last have identified the impactor responsible for the breakup of the parent body of the L-chondrite meteorites."

Indeed, little was known about the smaller asteroid that caused the collision somewhere between Mars and Jupiter. That is why the Swedish find is crucial for understanding of its origins. Scientists believe their discovery, to which they have given no name so far, calling it just a “Mysterious Object,” was a fragment of the "asteroid destroyer."

Though their theory is based on analyses of elements, comprising the meteorite, the discovery itself is so little (the meteorite is only 8 cm × 6.5 cm × 2 cm in size), that it could leave a possibility of linking it to known classes of meteorite.

"I think it's entirely plausible [that it's a new kind of meteorite], and it's a great study, but that's not a guarantee they've got it right," said Tim Swindle, a meteorite expert not involved in the research. "But if they didn't, it's because of new things we'll find out in future work, not because of their analysis."