Legs on eggs: Octopus’ 53 months nesting sets animal kingdom record

A deep sea octopus has taken motherly devotion to a new level after guarding her eggs for four-and-a-half years. Biologists say that this a new record, with no creature even coming close to this octopus’ feats.

Biologists from the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institution observed the octopus, using cameras from an unmanned submarine. The team was led Bruce Robinson, who has been observing deep sea life in the depths of Monterey Canyon for 25 years.

Back in May 2007 he observed a female deep sea octopus, which is all of 20cm in size, on the sea floor.

The creature stood out because of distinct scaring on her mantle and when Robinson returned a month later, he found the same octopus 1,400 meters below the surface.

"This was a chance to watch the whole brooding process," Robison said. "It was a fluke. No one before ever had a chance to see anything like it, so it was kind of bootleg science, but we decided to watch her again and again,” the San Francisco Chronicle reports.

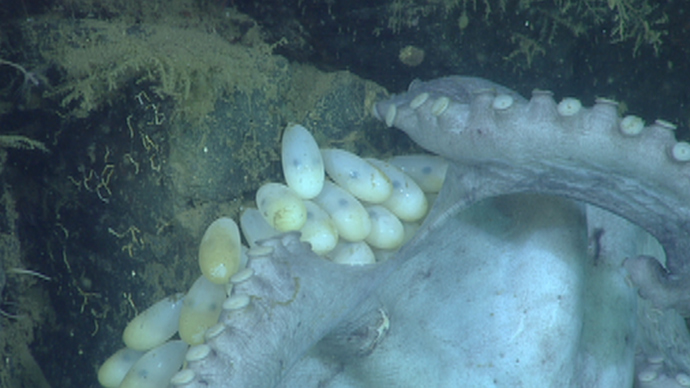

Over the four-and-a-half-year period, Robinson and his team made 18 dives and made plenty of observations. They saw how the eggs were growing in size, but also how the octopus was becoming smaller, which the research team believes meant she was not even leaving her eggs to search for food or rest.

"During that whole time we never saw her leave the eggs once," said Robison, whose team would watch the octopus closely for an hour or more each time they visited her rock. "We never saw her eat anything, and she paid no attention to the crabs and shrimp swimming by, except when she pushed them away with her arms because they were predators."

Octopus eggs hatch relatively quickly in warm or shallow water, with mothers needing to spend from one to three months guarding their eggs. However, the amount of time rises considerably the colder the water becomes. The temperature in the Monterey Canyon, where the octopus was brooding was around +3 degrees Celsius (37.4 degrees Fahrenheit).

The team, who published their scientific report in the journal PLOS ONE, noticed that when they first observed the deep sea creature, that the skin of her mantle was a shade of purple, which is common when octopuses start brooding. However as time elapsed her mantle became whiter, which showed she was starting to age.

In September 2011, the team once again made a dive to observe the octopus, however on this occasion, they did not find her as she had presumably died. They also found in excess of 160 open eggs, meaning that the young hatchlings had finally made it out into the deep sea.

Octopuses typically have a single reproductive period and then they die. Once they lay a batch of eggs, the female will stay to protect them until they eventually hatch.