Giant venomous jellyfish found off Australia coast

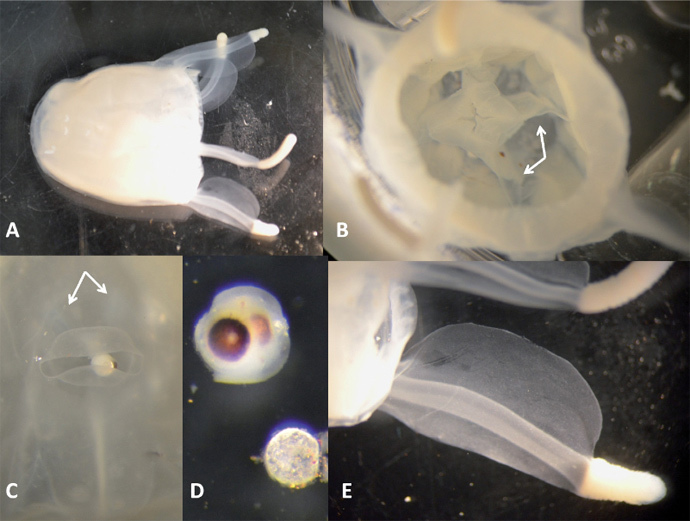

Two new species of extremely poisonous jellyfish have been found off the coast of northwest Australia. Irukandji jellyfish are normally the size of a fingernail, but one of the specimens is the length of an arm.

The smaller of the two is the Malo bella, which was found near Exmouth. The larger one, the Keesingia gigas, was caught in a fishing net off Shark Bay further to the south.

The discovery – which was made by Lisa-Ann Gershwin, a CSIRO scientist and director of Marine Stinger Advisory Services – brings the number of Irukandji species found globally to 16, nine of which are in Australian waters. Until now, there were only two species of jellyfish found off Western Australia.

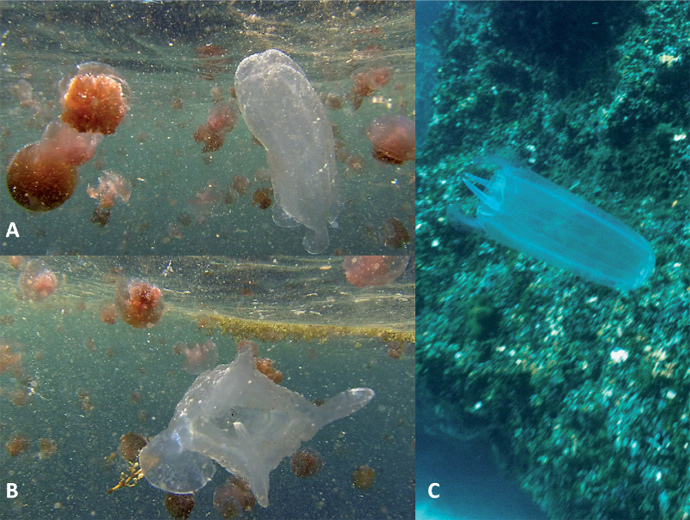

The Keesingia gigas is the length of an arm and can cause the potentially fatal Irunkandji syndrome – resulting in pain, vomiting, nausea, and in extreme cases stroke and heart failure.

Gershwin said the existence of the larger Keesingia gigas was previously known, but until now it had never been officially classified.

“It is absolutely humungous – the body is about 30 to 50 centimeters tall and that’s not including the tentacles. It’s an absolute whopper of a jellyfish,” she told ABC Australia.

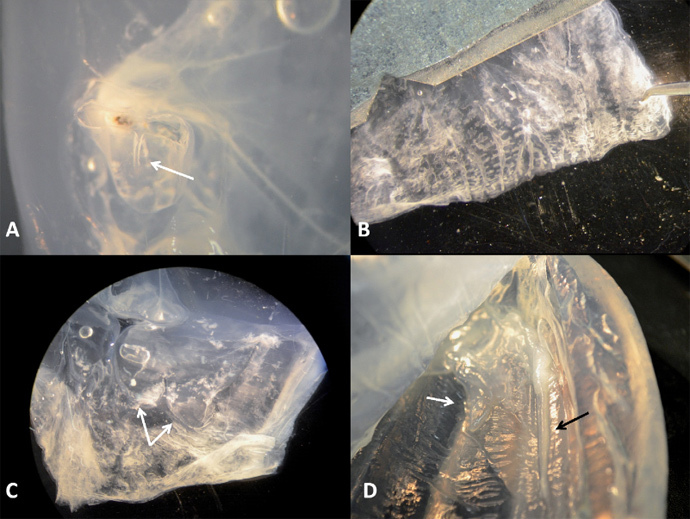

However, its features challenge what is already known about the Irukandji.

“The features it has put it in two quite distantly related families which is a great head scratcher. But in this case we were able to work out with DNA what it actually is related to, so it had a really surprising aspect to it,” Gershwin said.

The Keesingia gigas was first photographed in the 1980s. It was first captured in 2013 by marine scientist John Keesing, after whom the sea creature is named.

Gershwin said that neither the jellyfish in the photograph nor the two specimens have tentacles, adding that such a feature is very unusual.

“Jellyfish always have tentacles...that’s how they catch their food. The tentacles are where they concentrate their stinging cells,” she told the AAP news agency.

She said that some jellyfish shed their tentacles as a means of self-defense, but that there is no evidence that the Irukandji has that capability.

“I think probably it does have tentacles but by random chance the specimens that we photographed and obtained don’t have them anymore,” she said.

The specimens of the new jellyfish species will be kept at the Western Australian Museum. Dr. Jane Fromont, head of the museum’s aquatic zoology department, said that beachgoers should be alerted.

"Publishing this information means our beachgoers, fishers and surf lifesavers can be alerted about the fact that there's this really big jelly that looks kind of nice and you might want to touch, but maybe just leave that one alone," she said.

However, Gershwin added that there does not appear to be a direct link between the size of a jellyfish and its toxicity.