Super-hungry black hole gobbles star at rate previously thought impossible

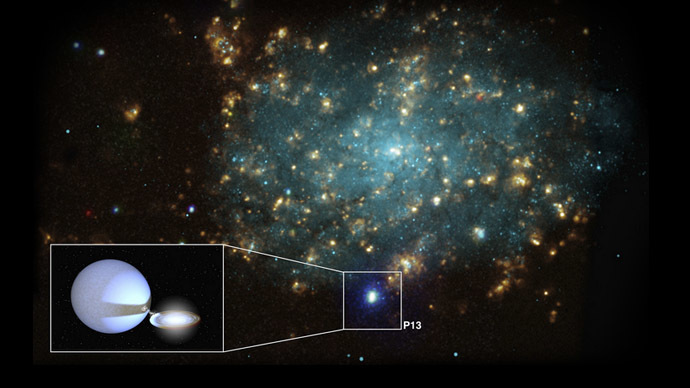

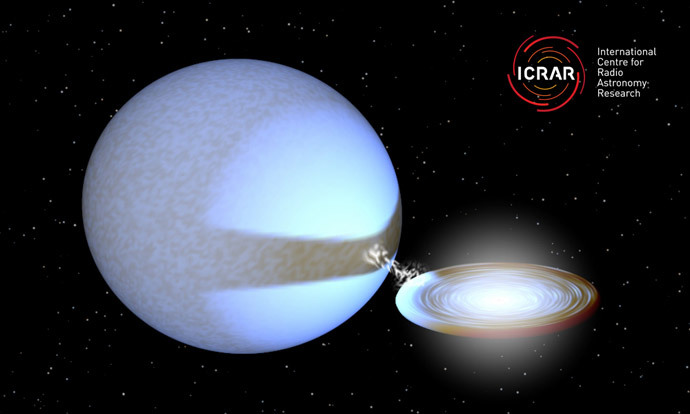

An “ultraluminous” black hole P13 in a remote galaxy is consuming a gas cloud belonging to a neighboring star about ten times faster than scientists previously believed was possible.

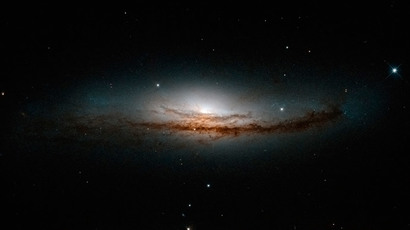

About 12 million light years from Earth, on the outskirts of the galaxy NGC 7793 the developments around a “luminous” black hole, known as P13, have caught the attention of astronomers.

The scientists were amazed by the speed at which P13 was sucking up a weight that is equivalent to the mass of the moon every three weeks, or the mass of Earth every four years.

P13’s “donor” is a blue supergiant star about 20 times heavier than our Sun.

"It was generally believed the maximum speed at which a black hole could swallow gas and produce light was tightly determined by its size," Dr Roberto Soria, International Centre for Radio Astronomy Research astronomer, said in a press-release. "So it made sense to assume that P13 was bigger than the ordinary, less bright black holes we see in our own galaxy, the Milky Way."

However, the research conducted by Soria, who works at ICRAR's Curtin University in Australia, and his colleagues from the University of Strasbourg, revealed that P13 – being at least a million times brighter than the Sun – was actually quite small. According to Dr Soria, “The black hole must be less than 15 times the mass of our Sun.”

The findings were published in the journal Nature on Thursday.

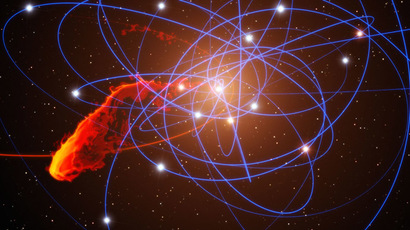

The star rotating around the black hole sent irregular light due to the proximity of the black hole’s X-ray illumination. "This allowed us to measure the time it takes for the black hole and the donor star to rotate around each other, which is 64 days, and to model the velocity of the two objects and the shape of the orbit," Soria said.

P13’s brightness associates it with a “puzzling” group of black holes, discovered in the 1970s – so-called ultraluminous X-ray sources. "These are the champions of competitive gas eating in the Universe, capable of swallowing their donor star in less than a million years, which is a very short time on cosmic scales," he explained.

What struck the scientists most was the fact that ultraluminous X-ray sources are usually intermediate-mass black holes – right between supermassive black holes, that form centers of many galaxies, and stellar-mass black holes, created during the deaths of stars. As it turns out, P13 stands out from this rule, being a stellar-mass black hole that is, nonetheless, unusually bright.

The prominent appetite of P13 made the researcher compare its performance with a Japanese eating champion: "As hotdog-eating legend Takeru Kobayashi famously showed us, size does not always matter in the world of competitive eating and even small black holes can sometimes eat gas at an exceptional rate," as cited by the International Centre for Radio Astronomy Research.

Black holes have long been a major source of interest of scientists – and inspiration of science-fiction writers. But these mysterious cosmic objects seem to have seen their black days recently.

The famous British theoretical physicist Stephen Hawking was first to blow our minds, claiming that “there are no black holes – in the sense of regimes from which light can't escape to infinity”. The denial of the classic definition of a black hole led to calling it a “grey hole” by the media.

But it was only the beginning, as this September an American physicist Laura Mersini-Houghton said that she had found mathematical proof that black holes do not exist in our universe.