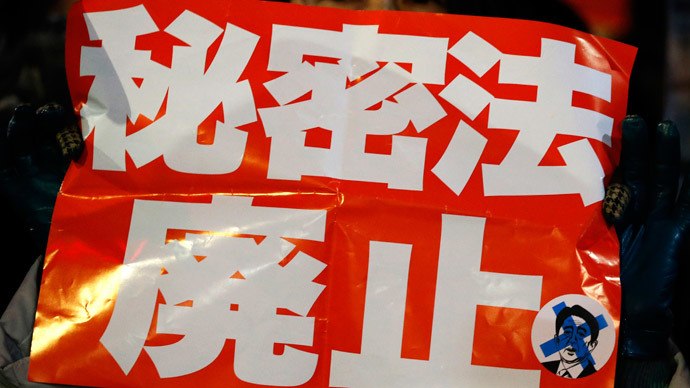

Hundreds of Japanese protest ‘unclear’ whistleblower law

Demonstrators flooded Tokyo’s streets over a just-activated secrecy law set to threaten the disclosure of government wrongdoings, as well as limit press freedom. The government hopes the added safeguards will lead to intelligence-sharing with the US.

Starting Wednesday, anyone leaking state secrets can get 10 years in prison. Anyone who becomes an accessory to the crime – such as a journalist – can get five. According to the Kyodo news agency, a total of 460,000 documents are to immediately gain classification under the law.

This fact led to hundreds of people with banners and tambourines filling the capital’s streets very early Wednesday, prior to the year-old law coming into effect – the exact same picture seen in November 2013, when they tried to prevent the document from being ratified.

"This terrible law must be revoked, but at least if we keep on protesting the government won't be able to do whatever it wants," Yumi Nakagomi, 59, told Reuters. "If we give up on this Japan will end up just like Russia or China, or North Korea.”

"This law will restrict the peoples' right to know," Tomoki Hiyama, one of approximately 800 people gathered in front of the parliament said late Tuesday. "It's full of ambiguity and will take us back to the 'public peace and order' controls of World War II."

Yukiko Miki with NGO Clearinghouse Japan explained to Reuters that the law will be enforced irrespective of circumstances under which the transgression happened. And although there are concerns that the people’s right to know will be affected, Deputy Chief Cabinet Secretary Hiroshige Seko moved to dissipate them.

"By applying the law practically and properly, explaining carefully how it is being applied, and reporting to parliament and making public how it is being enforced, the government plans to show clearly that the people's right to know will not be infringed on."

But the public maintains that Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s government fails to explain fully the ins and outs of how the law actually functions. The people don’t know what is deemed a secret and what isn’t, let alone what precautions they must take to avoid being charged, for example erasing online posts or other measures.

"It seems to allow Abe to do virtually anything by saying 'it's for the good of the country' without anybody knowing what they are actually doing,” Hisako Ueno, 60, told journalists.

Similar concerns were raised by the Japan Newspaper Publishers and Editors Association in a letter to Justice Minister Yoko Kamiwaka.

"It cannot be said that all our concerns have been alleviated,” it read.

READ MORE: Thousands protest in Japan against new state secrets bill

Disappointment with Abe’s handling of the situation is not new. A year ago in November, more than 10,000 took to the capital’s streets to kill the bill before it ever had a chance. They say their concerns remain largely unaddressed.

“The definition of what will be designated as secrets is not clear, and bureaucrats will make secrets extremely arbitrarily,” TV journalist Soichiro Tahara told Japan Daily Press in 2013.