The mechanism, which prevents the human brain from being littered up by outdated and useless memories, has been uncovered by US scientists.

READ MORE: Use of smartphones alters brain – study

Before encountering any familiar situations the brain makes a subconscious prediction on what it expects to come across.

But if this prediction turns out to be wrong the memories related to it diminish and are more likely to be completely forgotten, the researchers at Princeton University and the University of Texas-Austin said.

“This has the benefit ultimately of reducing or eliminating noisy or inaccurate memories and prioritizing those things that are more reliable and that are more accurate in terms of the current state of the world,” Nicholas Turk-Browne, an associate professor of psychology at Princeton University, said.

Turk-Browne used the example of “a trip to a coffee shop” to explain the memory filtration mechanism applied by the human brain.

The brain of a person, who comes to the coffee shop for the second time in a row, automatically predicts that he’ll be serviced by the same barista (Rachel), which gave him coffee on his first visit.

But when he sees another employee (Mike) behind the counter he instantly forgets about ever meeting Rachel as the information about her becomes irrelevant, he said.

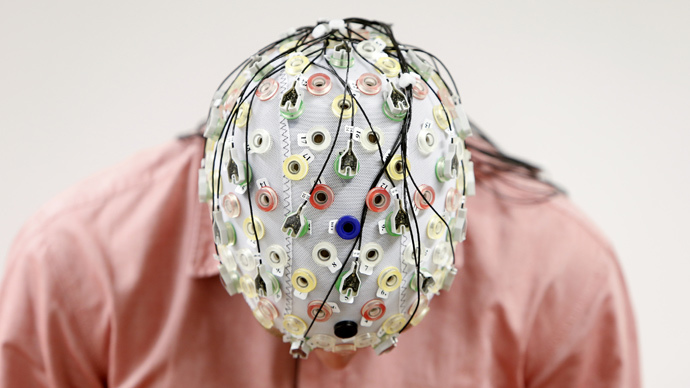

The scientists came to the conclusion after an experiment involving 24 adults, who were shown pictures in a specific sequence, while their brain activity was monitored by a functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) machine.

After analyzing the acquired data, they learned that the participants were more likely to forget the photo when their brain‘s prediction that it’ll be shown to them next was the strongest.

"Our specific hypothesis in the context of the experiment is that the bigger the prediction, the more the error and the more likely you are to forget the thing you were predicting," Turk-Browne stressed. "We think it's the error causing the forgetting.”

“How can we measure the error? That's difficult. But we know the error is proportional to the strength of the prediction. So we use the strength of the prediction as a measure of the prediction error," he added.

The researchers said that the memory is strengthened when a remembered object or event is encountered, while wrong predictions can lead to the memory’s degradation.

"This is a very general mechanism for influencing what people remember and forget on the basis of whether it can be reliably predicted given the situation in which it occurs or not," Turk-Browne said.

"People remember and forget a lot of things. This isn't going to explain all of remembering or all of forgetting, but this is an automatic, unconscious way the brain has to figure out when things turn out not to be really reliable in terms of how the world is structured,” he added.

The research was first featured in an article called "Pruning of memories by context-based prediction error," which appeared in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.