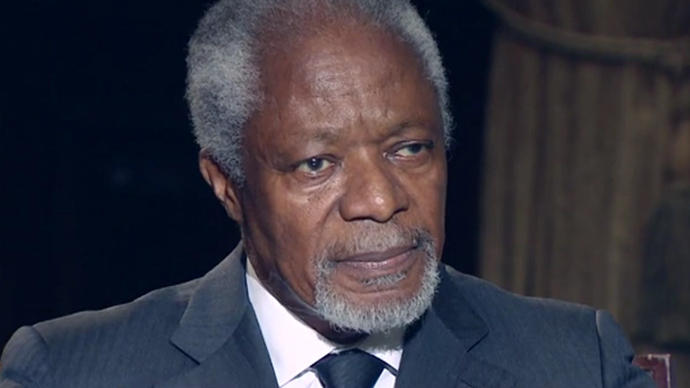

The fragile state Iraq is now in is directly linked to the US-led invasion of 2003, which happened without a US Security Council mandate, Kofi Annan, who was UN Secretary General between 1997 and 2006, told RT.

“You cannot disassociate the situation in Iraq today from the US intervention of 2003. Because not only did the intervention take place, but they dismantled the Iraqi Army, which was the tool of Saddam to maintain law and order,” Annan said in Oksana Boyko’s Worlds Apart show.

“The civil service, the Baathist Party were all [dismantled]. So the structures and state institutions vanished overnight, creating a very serious vacuum, which has led to where we are today. So I don't think anybody can argue with that. The link is clear,” he added.

Annan visited Moscow this week in his capacity as head of the Elders, a group of prominent public figures founded by Nelson Mandela in 2007. The group met Russian President Vladimir Putin and other prominent active and former statesmen to discuss most pressing international issues, including Ukraine, Syria and Iran.

The interview Annan gave to RT focused on the UN’s role as an international arbiter of conflicts, the costs of overstepping the UN Security Council in use of military force and potential mechanisms for making great powers accountable for breaking rules. He said one of UN’s bigger failures is that of not giving smaller nations a greater voice in world affairs and the inability to hold greater powers accountable for their wrongdoings.

“After the Yugoslav war, attempts were made to make leaders and people accountable. Several tribunals were set up – the tribunal for Yugoslavia and Tribunal for Rwanda, and there have been several indictments. And today, we have the International Criminal Court,” he said. “But what is interesting is that the big powers are not members of the Court, and yet they sit in the Security Council and refer smaller countries and others to the Court.”

“In effect, [they are] saying we are going to apply the law to the small people and the small countries, but we would absolve ourselves, it wouldn't apply to us. What sort of justice is that? It has to be, we have to aim for a system, and a legal system where the laws are applied fairly and consistently across the board.”

Annan said careful analysis of what a military intervention could achieve and what harm it may do is necessary before taking a step in that direction.

“You have to start on the basis that you should do no harm. You shouldn't do more harm than is necessary. So you have to assess the situation to see will the intervention help, would it have a positive aspect, or would it do more harm. And if you analyze it and you were to conclude that the results would be much more disastrous, then what's the point of intervention? What would the people gain? What are you offering them, if it's going to make their situation worse? And how do you explain to the world why you intervened?” he explained.

Not being a pacifist, Annan says sometimes using force is necessary, but it’s mostly more useful as a threat that forces negotiation than as a solution in its own right.

“Sometimes the threat of potential use of force is much more effective than actual use of force. When the other side knows that you have the capacity and you may use it, the attitude is different,” he said, adding that his own negotiation experience as a leader with no military force at his disposal was quite enlightening.

“But if the Secretary-General, the individual, is saying, look, be careful, you have to do the right thing otherwise you may provoke a reaction that will be much more brutal than the conversation I'm having with you, is something quite different. So, for me it's the threat rather than actually jumping in to intervention,” he explained.

Unfortunately now international politics is degrading in a sense that some players don’t seek negotiation with their opponents. They undermine the prospects of reaching an agreement by deliberately antagonizing and demonizing the other party. Genuinely seeking compromise is far more productive, Annan said.

“When you begin to call each other names, when you begin to demonize the other, when you begin to hate the other in order to accept yourself, you are really complicating the situation,” he said.

“Sometimes when you reach [for a compromise] you are able to get to understand what is it that is driving them, what is it that is making them behave the way they do. And you begin to work with that knowledge, you'd sometimes be surprised the progress you would make,” he added. “But if you're dealing with somebody that you have demonized, that you consider is worthless, you are starting a conversation on a very false basis. You've lost the conversation before you even get into it.”