Bacteria discovered 1,000 years ago in Japan is being used to grow a “second skin” that responds to a person's sweat. It could revolutionize sportswear and extend to other parts of our daily lives – including our lampshades and tea.

Researchers at MIT Media Lab's Tangible Media Group are using the Bacillus Subtilis natto bacteria to create a synthetic “second skin,” known as BioLogic, which physically moves and morphs when it is exposed to moisture. It opens up flaps on the "skin" that will allow sweat to evaporate when a person's body temperature or sweat volume reaches a certain threshold.

The idea to use the bacteria came while MIT PhD student Lining Yao was testing various microorganisms in the lab and realized that the natto bacteria grew and contracted based on how much moisture it was exposed to.

The bacteria “becomes a nano-actuator that expands and shrinks depending on different relative humidity conditions, such as the humidity level in the atmosphere or sweat on the skin,” Yao said.

She then gave herself quite a challenge – to see if those movements could be used to act like a machine, rather than an unpredictable organism.

The concept is part of what the MIT group calls Radical Atoms, a vision where materials themselves are interactive – known as “material user interfaces,” or MUI.

“We are imagining a world where actuators and sensors can be grown rather than manufactured, being derived from nature as opposed to engineered in factories,” Yao said in a press release.

Developing a prototype

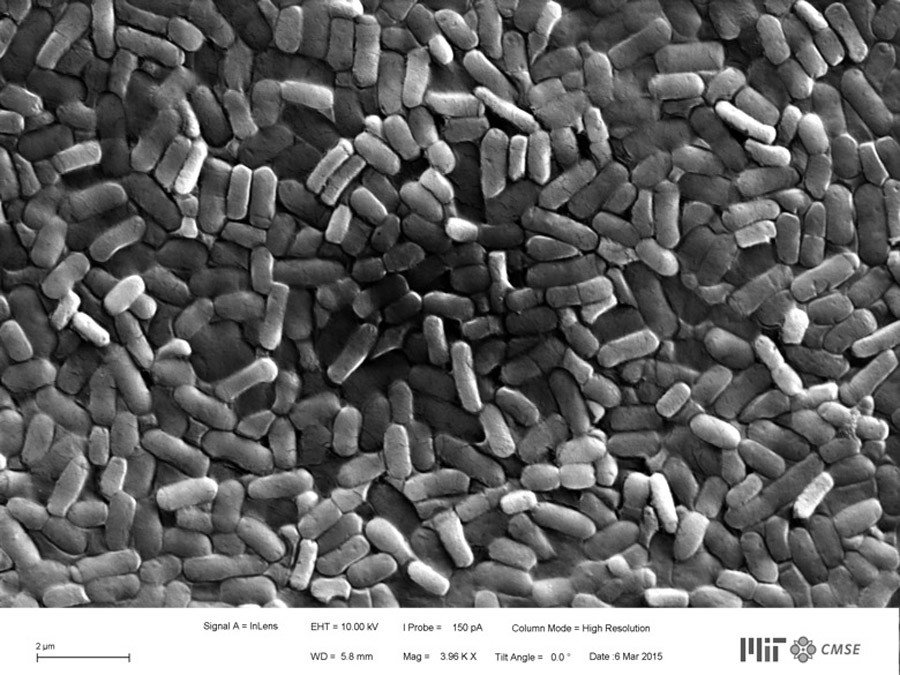

The realization of that goal requires the bacteria to be bio-printed onto wearable fabrics. To achieve this, Yao and her team first had to grow the natto cells in bioreactors. Their growth was carefully tracked using Atomic Force microscopes and other tools. Billions of the cells were grown, and were molded to be used in a micron-resolution printer.

The researchers then developed software to simulate the reaction of natto cells using 3D modeling tools. This helped them speed up the process of testing different printed designs.

READ MORE: Scientists genetically modify bacteria to detect & treat intestinal diseases, incl cancer

They developed dozens of tests of different behaviors using various patterns and shapes of cells. Those ranged from folding and bending to raising a texture on a cloth.

Printed film composites were then given to designers at the Royal College of Art who integrated them into clothing using heat maps of where the human body sweats the most and gets the hottest during exercise. The movable flaps were then placed on the clothing. Sportswear manufacturer New Balance was also part of the process.

But the technology isn't limited to athletes and those who enjoy a sweaty workout. According to a video released by the team, it could also be extended to kinetic lampshades that open and close with the heat of a light bulb, as well as teabags that signal when they're ready.

For Yao and her team, this is just the beginning.

“We are very keen to unveil and harvest responsive behaviors of microorganisms and repurpose/recompose them for design,” Yao told Gizmodo. “So far we know other microorganisms that react to light or electricity and swim in a certain pattern.”

Indeed, if the team continues its mission to encourage a “paradigm shift from building to growing,” many of the world's factories could soon be replaced with labs, and we could be introduced to technology we never thought possible.