Ice mummy's 5,300 yo stomach bug helps trace prehistoric migration

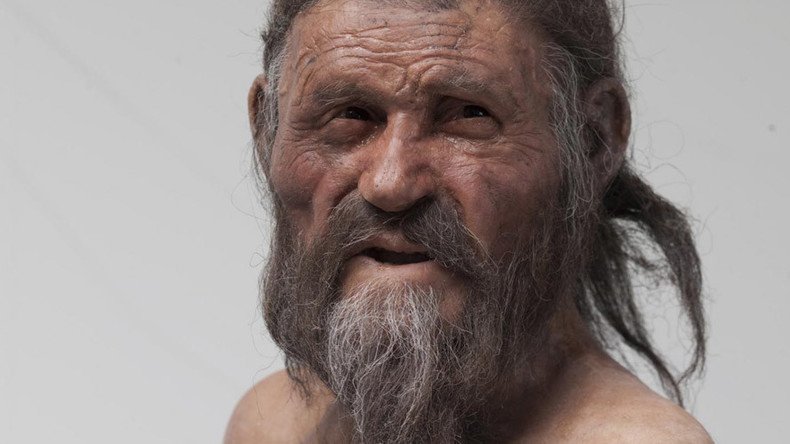

A group of scientists has found aggressive gut bacteria in a 5,300-year-old mummy, discovered in the Tyrolean Alps in 1991. It was dubbed Ötzi the Iceman. Helicobacter pylori, present in half the planet's population, speak volumes about the history of human migration.

When paleopathologist Albert Zink and microbiologist Frank Maixner from the European Academy (EURAC) in Bozen Bolzano first put samples from Ötzi's stomach under the microscope they didn't expect to find anything groundbreaking.

"Evidence for the presence of the bacterium Helicobacter pylori is found in the stomach tissue of patients today, so we thought it was extremely unlikely that we would find anything because Ötzi 's stomach mucosa is no longer there," Zink said in a public press release.

The challenge was to find a new way to proceed. "We were able to solve the problem once we hit upon the idea of extracting the entire DNA of the stomach contents," Maixner explained. "After this was successfully done, we were able to tease out the individual Helicobacter sequences and reconstruct a 5,300 year old Helicobacter pylori genome."

Helicobacter pylori typically spread among children when they play in the dirt. The bacteria can cause cancer and ulcers. The scientists found a potentially dangerous strain, to which Ötzi's immune system had already reacted. "We showed the presence of marker proteins, which we see today in patients infected with Helicobacter," the microbiologist said.

"Whether Ötzi suffered from stomach problems cannot be said with any degree of certainty," Zink noted, "because his stomach tissue has not survived and it is in this tissue that such diseases can be discerned first. Nonetheless, the preconditions for such a disease did exist in Ötzi."

After completing their stomach biopsy, the pair of URAC scientists gave the genome data to Thomas Rattei, a researcher from the University of Vienna, for analysis. Then there were a lot of raised eyebrows: "We had assumed that we would find the same strain of Helicobacter in Ötzi as is found in Europeans today. It turned out to be a strain that is mainly observed in Central and South Asia today," the computational biologist said.

The scientists believe there were originally two strains of the bacterium: an African and an Asian one, which at some point merged to become the modern European version.

Given that bacteria usually go round within the family, the history of the world's population can be traced in the history of bacteria. Up until now, scientists thought that Neolithic humans were already carrying this European strain by the time they gave up their nomadic life and took up agriculture. Research on Ötzi proves this was not the case.

"The recombination of the two types of Helicobacter may have only occurred at some point after Ötzi's era, and this shows that the history of settlements in Europe is much more complex than previously assumed," Maixner said.

The study has been published in Science magazine.