Bug from bioterrorism list kills almost 90,000 a year, study warns

A deadly disease caused by tropical bacteria is responsible for 89,000 deaths each year, many of which are never linked to the actual cause, a microbiology study warned. The bacteria are also much more widespread than previously believed.

Cases of melioidosis, which is also known as Whitmore's disease, are under-reported because its symptoms - including abscesses, fever and sepsis - are quite unspecific. Proper diagnosis also requires laboratory equipment that is scarce in developing countries, where Burkholderia pseudomallei, the bacterium causing it, is most commonly encountered, says a new paper published on Monday in the journal Nature Microbiology.

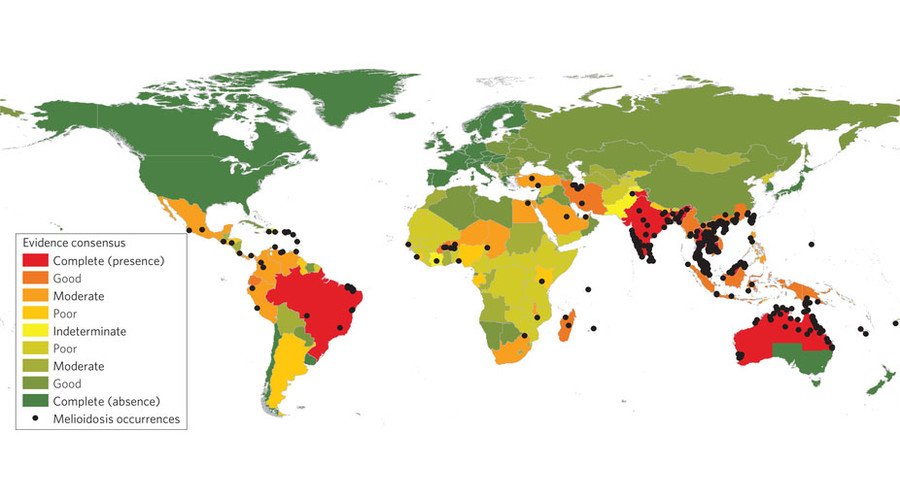

The disease was thought mostly to affect northern Australia and some Southeast Asian countries, particularly Thailand. But the study predicts that melioidosis is actually present in 79 countries, including 34 that had never reported the disease. In addition to the countries widely known to be affected, it may be found in water and soil in Latin America, Mexico, South Africa, some Middle-Eastern countries and most of South Asia and Oceania.

At the same time, the bacteria are resistant to many common antibiotics. When accurately diagnosed and treated properly, melioidosis death rates can be as low as 10 percent, but without the right medication they can rise to as high as 70 percent. When untreated, the disease kills up to 9 patients in 10.

The authors of the study say their model predicts that melioidosis killed 89,000 of the 165,000 people who contracted it in 2015. The figure is comparable to global deaths from measles, which kills 95,000 annually, and surpasses the mortality rate from leptospirosis or dengue - two diseases considered a high-priority threat by many international health organizations.

“Although melioidosis has been recognized for more than 100 years, awareness of it is still low, even among medical and laboratory staff in confirmed endemic areas,” said study co-author Dr Direk Limmathurotsakul, an assistant professor at Mahidol University in Thailand.

“Melioidosis is a great mimicker of other diseases and you need a good microbiology laboratory for bacterial culture and identification to make an accurate diagnosis. It especially affects the rural poor in the tropics who often do not have access to microbiology labs, which means that it has been greatly underestimated as an important public health problem across the world,” he added.

Burkholderia pseudomallei was studied as a potential bioweapon during the Cold War. It doesn’t spread well from human to human and the usual path for infection is when contaminated water comes into contact with a cut. But if it is spread as an aerosol, it can be highly infectious.

“The organism is much more dangerous when inhaled. The lethal dose drops dramatically if given by an aerosol route. So there are real concerns about bioterrorism use by an aerosol [method]," National Public Radio was told by Dr Donald Woods, who studied the bacterium for decades at the University of Calgary, but was not involved with the study.

A sample of the microbe escaped from a lab of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention at Tulane University National Primate Research Center in Louisiana last year, infecting a human and also four monkeys, two of which were subsequently euthanized. The lab has since been shut down.

The model developed by Limmathurotsakul and his colleagues predicts that Burkholderia pseudomallei could survive in the Louisiana climate, but so far soil and water samples collected there have come back clean.