As the Mars One mission draws ever closer, only 100 candidates remain out of a total of 2,000 who will help us colonize the Red Planet, forsaking their Earthly existence. RT sat down with two of the candidates to get an intimate look into their preparation.

In 2020, Mars One will send two living units, two life support units and a supply unit to the Red Planet, which will await the commencement of the mission in 2025, slated for arrival in 2026.

One hundred explorers, drawn from all walks of life, from Russia, the US, France, Nigeria, Japan and many other countries have been picked out of a much bigger bunch. Rounds 3 and 4 of the selection process will begin in 2016-17 and further reduce the figure. Then, Mars One will select six teams of four – two women and two men on each team. That is when training will begin, although study materials are set to arrive next month already. This should prepare them for the next two phases of testing.

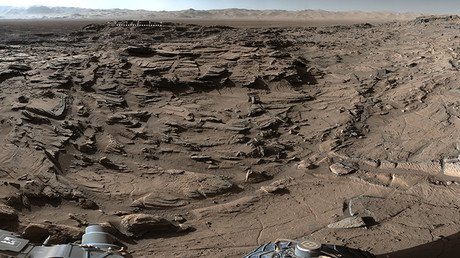

The future Mars colonists will dive headfirst into the unknown – their job being to explore a plethora of scientific research opportunities and means of survival on this highly inhospitable planet.

The question on everyone’s mind was how the volunteers mustered the courage to leave their home planet behind forever. One of the volunteers, ontologist (or, “a kind of data modeler” in his own words) Dan Carey, who is rather modest about his science background in applied physics, gave a simple answer:

“I have always been fascinated with space exploration and learning more about the solar system. Growing up, as I did, in the 60s with the Apollo and the Gemini programs in full swing, it was something that just grabbed my imagination and held on for the rest of my life. I don’t hate Earth. I love Earth, but we are talking Mars here.”

READ MORE: Lunar base not as far away or as expensive as we think – study

Like Carey, Josh Richards is a kind of jack of all trades, with an applied physics and astrophysics background, which he never really got to use, serving instead as engineer (primarily in explosives) in the Australian and British militaries, who now performs as a standup comedian. He believes his engineering skill set is “handy, but super-handy on Mars,” although, “essentially, where I am working now is trying to bring comedy into space science education,” he jokes.

The Australian says he’s been “bouncing around doing all sorts of weird and wonderful things” in preparation, including spending “five days locked inside a glass and steel box.” This was “all related to the DVD release of The Martian in Australia, and so, I got to play Mark Watney [Matt Damon’s character] for five days.”

There has been a slew of reports from last year alleging that Mars One is all a big hoax, that, among other things, it has no money – no contracts with aerospace suppliers (the ones behind the technology), no publicity or TV people behind it, or any endorsements from major brands.

Thankfully, “a lot of that isn’t entirely correct,” Carey says. “They are pursuing the investments in order to get things going. There are contracts with the people who are doing the initial designs for the life support system, the communication satellite… you have to have those before you get a contract to actually go out and build something.”

“There are things that have to happen in an order, and Mars One is pursuing those things in that order.”

Both candidates remember asking themselves at every stage of selection whether they had it in them to proceed and really commit to their lives of solitude on another planet. Carey believes nothing comes close to making that first important step for humanity, and so believes it’s worth the one-way trip.

Richardson recalls a funny coincidence: he’d first heard of Mars One while writing a comedy routine about sending people on one-way trips to other planets. He remembers centering on his frustration that we’ve got the technology to send someone up there, but not to bring them back.

“So the show that I was looking to write was quite angry: I was sort of frustrated that we as a species hadn’t been brave enough to go out into the solar system. And as part of my research, I found an organization planning to do exactly that,” he says. “So the one-way element is actually the biggest appeal for me.”