She is my son: The gender-bending children of Afghanistan (RT DOCUMENTARY)

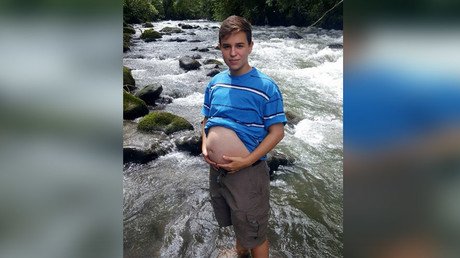

The curious case of 'bacha posh' takes RT to Afghanistan – a society so patriarchal that a family having several daughters and no sons is a social stigma that’s impossible to shake. This leads to some girls being forced to live as boys. Some for life.

“I have seven daughters and no son,” says Mohammed, a father.

His daughter, Amena, sitting nearby, somberly confirms what needs to be done in such cases.

“Even though I’m a girl, I must become a boy. I want to do something good for my family, for my father, that’s why I’m a ‘bacha posh’,” she says.

The Persian phrase ‘bacha posh’ literally translates as ‘dressed as a boy’. It is a cultural practice in parts of Pakistan, Afghanistan and Iran, whereby one of the girls assumes the role of a boy, her true identity only known to her parents and siblings. She dresses as a boy, plays football as a boy, goes to school - like boys do - and can move about town freely. Even escort her sisters.

The benefits of education are obvious. And the family, particularly the father, can have some peace away from the judgmental public eye.

But how do the children cope with such major transformations? Each individual story is unique. We met Fazilya, Asiya, Najla and Amena – all unique young ladies from different backgrounds. One of them, Fazilya, was raised as a boy from birth. Outside her household she is known as Abos.

It becomes apparent throughout the course of the documentary that limitations don’t always have to be crippling. Some children even enjoy being given the role of a boy, as they walk around in jeans, scale fences and play football with their male friends. Others feel it is the honorable thing to do.

But others yet, like the older Najla Tofan, have a different perspective on life altogether. They have learned in childhood that only men in Afghanistan enjoy any measure of real freedom – the freedom to move about alone, decide what to do and in what order. They retain their femininity and gender identity quite well, even into their late teenage years; at the same time, they never take their eye off the ball, always playing the role of the boy masterfully.

Away from her office work, Tofan teaches Taekwondo in the only girls’ school in the area, hidden away deep in a cellar. When the class is over, she heads to evening school.

“I feel good dressed as a man. I feel stronger. I feel like a man. And I like it.”

While some girls’ identities seem to end up changed irreversibly, others have no problem switching back. When some bacha posh come of age, they go back to dressing as women, while their parents attempt to marry them off – more often than not, to a relative. Tofan is a rare exception. She has pointedly refused to start a family and have children.

Even in deeply-conservative Afghanistan, some choose to accept the choices a girl makes when she seamlessly transitions between her two identities in the course of the day.

Join RT on this journey into Afghanistan to find out just how little you really knew of this fascinating regional custom.