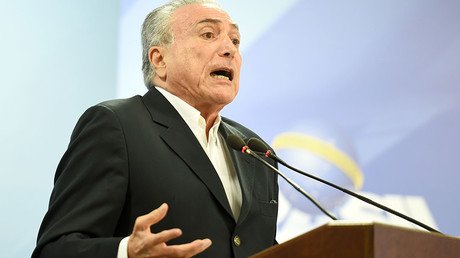

Top Brazil court leaves President Temer in office over alleged illegal 2014 campaign funds

Brazil’s top electoral court has voted against removing President Michel Temer from office over allegations of illegal campaign financing during the 2014 presidential election, when he was Dilma Rousseff’s running mate for vice-president.

The Superior Electoral Tribunal, known as the TSE, voted 4-3 against annulling the result of the election that saw Rousseff elected as president and Temer as vice-president.

Temer, 76, who replaced Rousseff when she was impeached last year, is being investigated separately for corruption and racketeering. There have been calls for the center-right leader to go.

“We cannot be changing the president of the Republic all the time, even if the people want to,” the court's chief judge, Gilmar Mendes, who backed the impeachment of Dilma Rousseff, said on Friday, as cited by Reuters.

“There are serious proven facts, but not enough to annul the mandate,” he added, according to AFP.

Justice Herman Benjamin, the chairman of the case, had called on the court to deem the Rousseff-Temer presidential ticket illegal, claiming that the campaign used funds illegally obtained from the state-run oil giant Petrobras that came from multi-million-dollar contracts with construction firms, Folha De S.Paolo reported.

On Thursday, however, the court had ruled not to allow as evidence in the case key plea-bargain testimony from some 77 executives of the Odebrecht construction giant, who said millions of dollars in bribes and illegal campaign contributions, including to the Rousseff-Temer ticket, had been funneled.

Temer’s spokesman Alexandre Parola said after the ruling that the president viewed the decision as “a sign that the national institutions continue to guarantee the smooth functioning of Brazilian democracy.”

However some argue the acquittal, which clears Temer to serve the rest of his term up until 2018, was wrong at its core.

“This catastrophic ruling prolongs the survival of a government that has lost all credibility and can no longer govern,” professor of ethics and political philosophy at Campinas research university in Sao Paolo, Roberto Romano, told Reuters.

“No democracy can come out unharmed from the institutional free-for-all that Brazil is going through,” Rio State University political scientist Mauricio Santoro told AFP, slamming “the degradation of the rules and of public life.”

A political science professor at Fundacao Getulio Vargas, Claudio Couto, called the court’s decision “demoralizing,” adding that more scandals in the administration were likely.

“But for now, the trend seems to be a weak Temer administration going forward, with little chance of passing any meaningful measures,” Couto told AP.

Last month, the Brazilian Supreme Court authorized a criminal investigation into allegations that Temer had reportedly paid hush money to the former speaker of the house and arranged bribes. Brazilian prosecutors said they had received recordings allegedly exposing the president and his aides and allies engaging in bribery and corruption schemes involving the country’s biggest meatpacking company, JBS.

The company’s owners, brothers Joesley and Wesley Batista, handed over the tapes to prosecutors as part of their plea bargain. Temer reportedly talked with Joesley about cash payments to the former Speaker Eduardo Cunha, who is in jail for his role in the Petrobras corruption scandal.

Cunha is believed to be instrumental in Rousseff’s 2016 ouster, paving the way for Temer to take office.

In 2016, Temer and his associates managed to get Rousseff dismissed, accusing her of manipulating statistics to conceal the country’s economic woes. Rousseff was suspended in May 2016 and impeached by the Brazilian Senate in August.

To put Temer on trial, the charges against the president have to be approved by two-thirds of the lower chamber of Congress, where his ruling coalition has a majority.

“The days ahead will be very difficult for Temer. The corruption investigations are just starting,” professor at the CERS law school and FGV think tank in Rio de Janeiro, Flavia Bahia, told Reuters.