‘Very emotional’: Pakistani ‘honor revenge’ rape survivor watches opera based on her story

Mukhtar Mai, a woman at the center of a high-profile case involving a so-called ‘honor revenge’ rape in rural Pakistan, has traveled to the US to watch an opera based on her story.

“I was very emotional when I first started watching it and began reliving the incident in my mind,” Mai, 37, told AFP on Friday, after attending the Los Angeles premiere of Thumbprint.

“But then as the opera progressed, it became easier to watch and I felt more courage,” she said.

The 2002 rape case involved a highly criticized practice in rural Pakistan that allows village elders to approve the rape of a woman as a form of punishment for her or another family member’s misdeed. The rationale is that damage to the honor of an offended family is compensated by an “eye-for-eye” injury to the honor of the woman’s family.

Mai was punished for adultery allegedly committed by her younger brother, who was 12 years old at the time. The boy was accused of becoming intimate with a woman from a family in the Mastoi clan, which is more powerful than the Shakoor clan of Mai’s family. That accusation was later proven to be false, apparently leveled to cover up the rape of the younger brother himself by Mastoi men.

The village council wanted to settle the conflict by marrying the boy to the woman he was accused of seducing and marrying a Shakoor woman to a man from the Mastoi clain. However, the Mastoi insisted on a tit-for-tat punishment. When Mai came to the council to apologize for her brother’s alleged misconduct, she was abducted and raped by four men from the Mastoi clan.

A Pakistani woman in her position is expected to commit suicide rather than live under the social stigma of being a rape survivor, but Mai chose to fight for justice and hold her rapists and their accomplices accountable. Unexpectedly, the alleged culprits actually faced prosecution and were found guilty as a result.

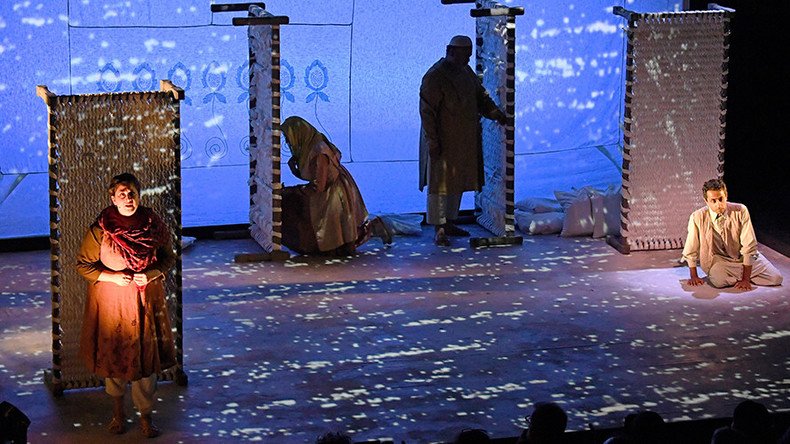

The opera by composer Kamala Sankaram and librettist Susan Yankowitz, which first opened in New York in 2014, recounts the rape and Mai’s defiance, leading to six people eventually being sentenced to death. The real story, however, is far less cathartic. After a long battle in several Pakistani courts, her rapists’ sentences were overturned and all six men are now living free.

“My rapists live across from my house and I try not to cross paths with them,” said Mai, adding “when I walk past, they taunt me and make catcalls.”

“All four of the men who raped me and the two village elders who ordered the rape are free,” she said, noting “they will only learn that what they did is a crime if they are punished.”

Mai used the compensation money paid to her to open two schools and a women’s shelter in her village. In a strange twist, the children of her rapists attend her school, while the daughters of some of the village elders who approved her rape have sought refuge in her shelter, she told AFP.

“Even though some members of my own family were outraged, I told them I could not turn away the kids as the school is here to serve everyone in the community,” she said.

She also said she has grown tired of the attention her case brought to her compared to that focused on her rapists, who are never confronted about their crime.

“I am the one who is always interviewed and put forward in this case,” she sighed. “Why doesn’t anyone confront them, why doesn’t anyone point them out in the street and say, ‘These are the people who committed horrific acts against Mukhtar Mai?’”