US sanctions Russia: Who, why & how we got here

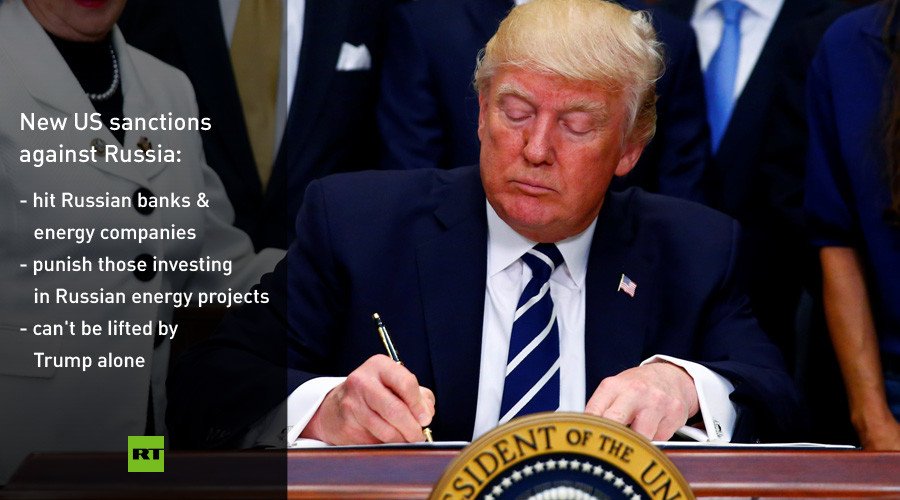

On Wednesday, US President Donald Trump grudgingly signed into law a bill imposing new economic sanctions against three nations, including Russia, designated as “America’s adversaries” in the name of the law.

RT takes a look at how the act came into being and who would be hurt by it.

Why new anti-Russian sanctions?

There is a strong perception in Washington that Russia interfered in the most recent presidential election and may have colluded with the Trump campaign to have him elected. The exact nature of the alleged interference differs depending on the commentator. The more serious accusations claim that the Russian government was behind the hacking of DNC servers and the email account of Hillary Clinton staffer John Podesta. But some consider that even coverage of the US election by Russian media outlets like RT amounted to interference.

BREAKING: ‘US-Russia relations at all-time & dangerous low. Thank Congress’ – Trump https://t.co/ZtILFdo44mpic.twitter.com/ubmgzb2EnB

— RT America (@RT_America) August 3, 2017

The suspicion of collusion on the part of team Trump is fueled by his public statements favoring deescalating America’s relations with Russia and communications between some of his campaign members and Russians, including now-retired Russian Ambassador in Washington Sergey Kislyak. The US president maintains that his critics have blown the issue out of proportion. Nevertheless, the alleged collusion is currently being investigated by several actors in US, including the Congress and the FBI.

The new round of anti-Russian sanctions is meant to both punish Russia for the alleged interference and to prevent Trump from unilaterally lifting sanctions against Russia imposed by the Obama administration.

What do new sanctions target?

Mostly, Trump and the Russian energy and finance sectors.

Trump is being partially stripped of his presidential authority to form a foreign policy vis-à-vis Russia. The act forces him to sanction Russian entities and forbids him from lifting sanctions already in place without congressional approval.

Russian banks affected by sanctions will now have an even harder time getting loans from creditors. The same goes for Russian energy companies.

More importantly, the act limits investments into Russian energy projects connected with the Arctic or involving fracking as well as into Russian natural gas pipelines. The act specifically states that the US will “continue to oppose the Nord Stream 2 pipeline given its detrimental impacts on the European Union’s energy security, gas market development in Central and Eastern Europe, and energy reforms in Ukraine.”

Europe ready to retaliate

Unlike the previous rounds of sanctions, this one was imposed without proper coordination with European nations. Several of them, including Germany, voiced outrage with the act’s potential to punish European companies for conducting projects with Russia crucial for the European economy.

'EU must defend its interests even against #US, if anti-Russian sanctions will hit us, we will react' – Juncker https://t.co/KXInfKHuQz

— RT (@RT_com) August 3, 2017

Nord Stream 2 is a gas pipeline that would deliver Russian natural gas directly to Germany, bypassing any transit countries. The project is meant to ensure continued supply of the fuel regardless of what happens in Ukraine, a country with a history of spats with Russia over the use of its transit facilities, which has not been investing into modernization of its gas pipelines and which shows little sign of economic recovery since the 2014 political crisis toppled its previous government.

The US targeting European entities and undermining its energy security for the sake of Ukraine’s transit profit didn’t make the Europeans thrilled. Many believe that under a guise of protecting its democratic institutions the US is simply trying to take over the Russian share of the European energy market, ensuring sales for its liquefied natural gas.

How does Moscow hit back?

Following the legislation approval by the US Congress, Russia hit back, targeting the American diplomatic mission in Moscow, cutting staff numbers and taking back property used by the Americans. In some ways, the moves were not response to the bill per se. Rather they were a seven-month-old response to previous President Barack Obama’s decision to oust 35 Russian diplomats and seize Russian diplomatic properties in America. Ironically, Obama’s move was meant to punish Russia for the alleged interference in the 2016 election too.

READ MORE: US compounds in Moscow: What they lose and what they get to keep (PHOTOS)

Moscow’s response, however, was stronger than last year’s expulsion. It ordered that the US State Department limit the number of its personnel in Russia to what Russia has in the US. Washington did not initially disclose the exact number of people affected by the restriction, but Russia says 755 staff jobs have to be cut.

Russia didn’t act in response last year, saying it didn’t consider actions of the outgoing Obama administration relevant and was willing to give Trump a chance to deliver on his promise of better relations. Now Moscow apparently no longer believes that he will and says it reserves the right to retaliate further for the new sanctions.

Old sanctions game

The US has a long record of using unilateral sanctions against other nations, and Russia has long been on its hit list. In fact, even the collapse of Soviet Union with all the expectations of the “end of history” under West’s leadership was not enough to convince Washington to lift sanctions against Moscow.

The infamous Jackson-Vanik amendment of 1974 survived for four decades and was lifted in December 2012 only because it was replaced by another round of human rights-based sanctions, the Magnitsky Act. The stated goal of adopting the Jackson-Vanik amendment was to convince the Soviet Union to allow its Jewish population to repatriate to Israel.

Washington upped the sanctions game after the political crisis in Ukraine in 2014, enlisting Brussels and other allies for the effort and claiming that Moscow must pay a price for its role in it. So far, European farmers seem to be paying the price, by losing the Russian market to the US-Moscow standoff.