Yes, Syrian refugees can return to Aleppo… and do so in their 100,000s

Aleppo, a city retaken by Damascus from rebels in December last year, has become a major destination for displaced Syrian returning home in 2017 as numbers of returnees to Syria spills over 600,000, according to the UN.

Over the first seven months of 2017, over 600,000 displaced Syrians returned home, the International Organization for Migration (IOM) said Friday, citing its own figures as well as those of the UN Migration Agency and partners on the ground. The returnees are overwhelmingly internally-displaced people, but 16 percent returned to Syria from other nations, primarily Turkey. The number almost matched that recorded in the whole of 2016.

An estimated 67 percent of returnees went to government-controlled Aleppo Governorate, with the provincial capital itself being the primary destination. Among other places where refugees went in significant numbers, according to ICO, is Al-Hasakah Governorate, the north-eastern province dominated by Kurds.

The city of Aleppo – the largest in Syria prior to the conflict – was retaken by the government army last year, aided by Russia, with hostilities ending in mid-December. For years before that, it was divided between two parts, held respectively by government forces and by a disjointed collection of militant groups, including hardcore jihadists. The battle for the city ended with a ceasefire deal, which allowed remaining rebel forces and their families leave Aleppo and go to Idlib governorate, which currently remains a rebel stronghold.

Earlier an increasing number of refugees returning to their homes in Syria was reported by the UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR), which said more than 440,000 internally-displaced persons and 31,000 refugees in other countries had done so over the first six months of 2016. Aleppo and other government-controlled governorates like Hama, Homs and Damascus were mentioned as destinations for the returnees.

“Given the returns witnessed so far this year and in light of a progressively-increased number of returns of internally displaced people and, in time, refugees, UNHCR has started scaling up its operational capacity inside Syria,” the agency said.

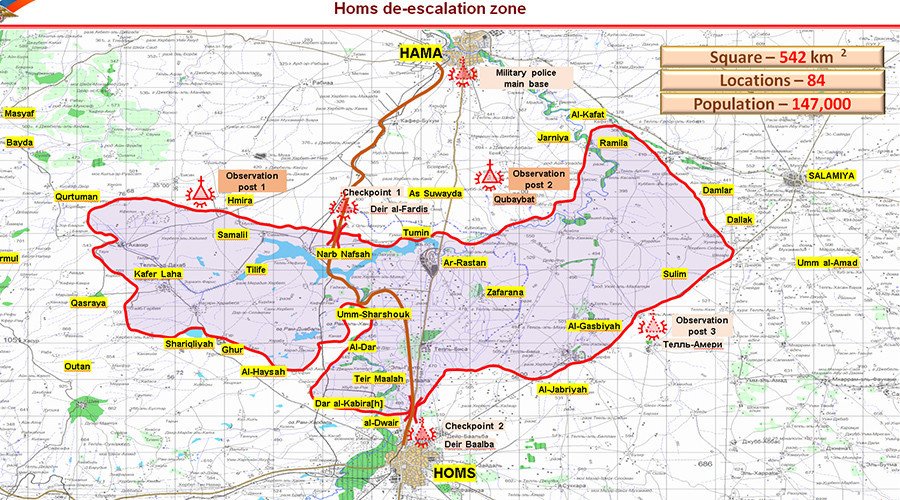

De-escalation strategy working

The situation is far from rosy of course, according to IOM. The number of people forced to leave their homes in 2017 still outweighs that of returnees, with over 808,000 people estimated to be displaced. Around 10 percent of those who returned in 2016 and 2017 have ended up fleeing their homes again.

Almost 20 percent of the returnees have no secure supply of food and access to water and health services is a problem for some 60 percent, a testament to the damage the Syrian war has taken on its civilian infrastructure.

For some people going back is arguably the best of bad choices. Refugees may prefer the uncertainty of their homeland to staying in refugee camps, where they face a shortage of aid, unemployment, mistreatment by host nations and a general lack of prospects for change for the better. This may be true even for those, who managed to get to richer and more secure places like Europe.

Some have no choice at all, being forced to leave as part of deal sealed by warring factions in Syria.

Still, observers believe that the general trend signals hope for the strategy of de-escalation taken by the Syrian government with the backing of Russia, Turkey and Iran.

“Russia has played a leading part in this by getting everyone at the table regionally despite serious differences between Iran and Turkey,” believes Kamal Alam, analyst on Syrian affairs.

“Moscow has successfully convinced the two to coordinate the de-escalation and bring stability in Syria. Russian military police and diplomacy combined have also given confidence to the Syrian Kurds and various elements of the opposition to play a positive role.”

The strategy focuses on curbing hostilities by establishing clear lines between parts of Syria under control of different parties, which would ultimately seek a political solution to the six-year-long conflict. And apparently for many Syrians, an absence of a shooting war in their neighborhood is more important than whatever political differences the rebels have with Damascus, Alam believes.

“After six years of war and uncertainty many Syrian refugees crave the stability they once had under President [Bashar] Assad and are returning home,” he told RT.