The latest innovation in 3D printing – artificial ears – feel, look and behave identically to human ones. The new product developed in the US could provide patients who are missing all or just part of their ear with a chance at reconstructive surgery.

Cornell biomedical engineers and Weill Cornell Medical College physicians published their study online in the PLOS ONE journal on Wednesday.

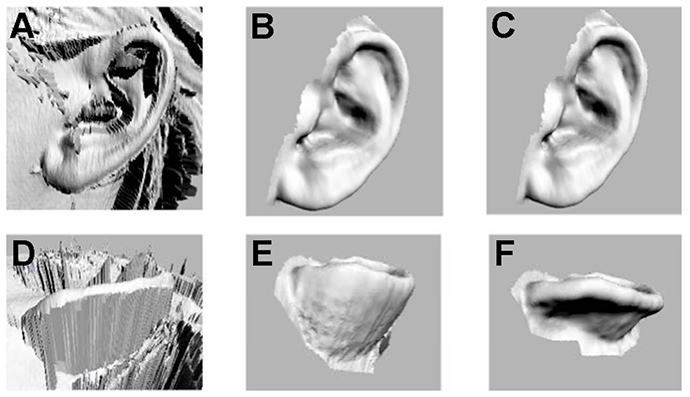

They show how they developed an ear over the course of three months by inserting living cells into an injection mold and then growing cartilage in the shape of its mold.

"This is such a win-win for both medicine and basic science, demonstrating what we can achieve when we work together," co-lead author Lawrence Bonassar, associate professor of biomedical engineering at Cornell, told AP.

According to the study, the first implant could be tried in around three years.

Researchers began the project by creating a digitized 3D image of a human ear, which was used to build an ear-shaped mold using a 3D printer.

Then they injected a gel made of living cow ear cells and collagen (a substance used to make gelatin) into the mold and the ear was done.

The production part took less than two days: only half a day to build the mold, a day to print it, 30 minutes to insert the gel, then wait 15 minutes and everything was ready to go.

Scientists tested the artificial ears by implanting them on the backs of rats and it took one to three months for the ears to grow. Rodents are often used by scientists to test the growing of artificial ears.

"We trim the ear and then let it culture for several days in nourishing cell culture media before it is implanted," Bonassar told AP.

The need for the product is there. Thousands of children who are born with ear deformities and those who have lost an ear during their life could benefit from the new technology.

The most common deformity is microtia, when the external ear does not fully develop. In US one to four children per 10,000 are born with it, according to the study.

People born with microtia usually have an inner part of the ear fully functional, but they still have impaired hearing because they are missing part of their external ear.

"A bioengineered ear replacement like this would also help individuals who have lost part or all of their external ear in an accident or from cancer," co-lead author Jason Spector told Live Science.

Researchers identified the best time for implantation for the kids to be at around the age of five or six, when the ears are at 80 per cent of their adult size.

The study says that a chance of rejection during implant procedure could be potentially decreased by using human cells from the same patient when constructing the bioengineered ear.

Before this point, technology only allowed to build replacement ears with a foam-like consistency or by using a patient's harvest rib, the latter is a painful process and ears still often looked unnatural and did not properly work.