The death this week of Allan Chumak will not mean much to many younger Russians, while older countrymen would be forgiven for assuming he had passed away years ago. But at the collapse of the Soviet Union, he led one of the most bizarre public crazes in history.

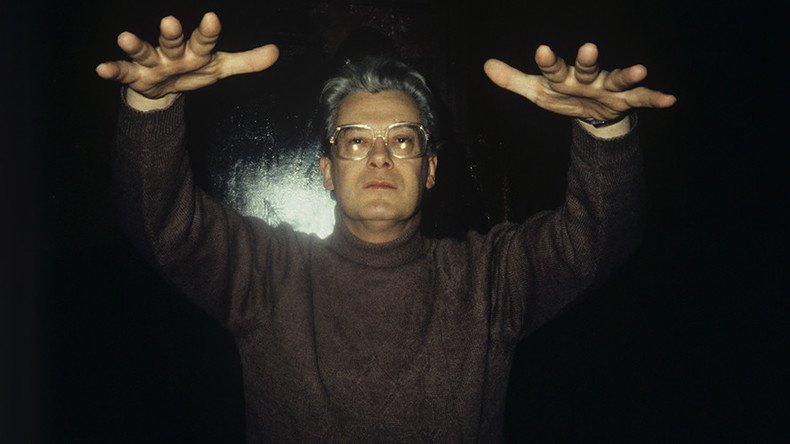

The TV screen shows a middle-aged man with a bouffant and square-rimmed glasses soundlessly making strange repetitive gestures – pushing back force fields, sweeping away bad energy, perhaps stroking a giant invisible feline. It’s impossible to say what he is doing, as he himself explains nothing, moving his lips noiselessly, save for an occasional sigh or mewl at moments of peak concentration. In a medium that shudders at dead air and static images, this ritual goes on for several minutes that seem like an eternity.

On the other side of the screen are millions, perhaps tens of millions, of Soviet citizens. Many have placed bottles of boiled tap water or creams as close to the cathode ray tube as they can, in the belief they will be “charged” with the healer’s powers. Some are afflicted by series medical conditions, but the healer has promised that his séance is capable of remedying problems ranging from allergies to paralysis.

It is the summer of 1989, two years before the USSR falls apart. Just months earlier, the man on the screen, the 54-year-old Allan Chumak, was better known as a former sports commentator, and even then mostly to his colleagues.

Over the next several years he will fill stadiums on his own. No goals, no warm-up acts. Chumak himself said that after one month of his pre-recorded shows, 6 million people sent requests and letters of gratitude, likely a truer claim than any he made on air.

For such a figure to dominate the public consciousness in just months, the cosmic flows need to align with perfect inner harmonies, to borrow from the healer’s own terminology.

It’s the height of Perestroika. Old certainties are fading fast, not least faith in the Soviet healthcare system, free and available, but short on new generation drugs, high-tech equipment and magic. Indeed, it is the atheist materialism of Communism that seems less appealing, now that the system it underpins fails to stock shelves even with basic goods.

Glasnost allows the vacuum to be filled at speed. There are still only five channels – if you live in a big enough city – but they are no longer exclusively broadcasting repetitive party propaganda. Chumak really is a breath of fresh air, yet he also receives authority from being on stuffy state television.

With only vague remnants of Christianity and everyday superstitions in most heads, Chumak’s audience is receptive to the point of naivety. His own philosophy, which he says came to him at 42 through an inner voice, is a cannily non-specific mix of the cosmic and spiritual, and like his performances promises everything yet commits to nothing.

A one-man target of Beatlemania – crowds spontaneously gather outside his flat – Chumak has his own Rolling Stones to contend with. Unlike the kindly white mage Chumak, Anatoly Kashpirovsky is a black-clad, iron-pumping, demonic presence. In his broadcast performances he banishes illnesses by growling at them in a menacing low voice, while during his live shows the hypnotist makes women swoon and collapse. Though there is one fortuitous trait they share – the feats of both can be performed remotely, even through a screen. Chumak and Kashpirovsky become friends, but then engage in a bitter decades-long feud centered around establishing who appeared on TV first.

The magic could not last. Chumak managed to monetize his gift by mass-producing “charged” water and creams, but by the time he and his ilk were officially banned by the Ministry of Health for “advocating pseudoscience” in 1993, interest was on the wane anyway. One part of the audience cringed at their earlier selves rushing to fill jars in time, another moved on to a new generation of psychics, who made corpses levitate or claimed that they were reincarnations of Jesus, rendering Chumak’s persona staid, his magic underpowered. Chumak did not retire to penury, but returned to playing to his core fans in smaller venues, and charging clinically diagnosed patients hundreds of dollars for one-to-one healing sessions – much like working psychics around the world.

But all that is the post-script. For those two or three charmed years, Chumak was not just a celebrity, but the nexus of the people’s mood – newly curious, strangely innocent, and irrationally hopeful. Perhaps regret and disillusion were the inevitable upshot, and not even a face-to-face spiritual recalibration from Chumak could have staved off the hangover. But in an epoch of flawed heroes, he did more than others to exploit and disappoint, whether consciously or sincerely.

Igor Ogorodnev, RT