Revolutionary corpse: Why and how Russia still preserves Lenin in its heart

As Russia marks the centennial of the Bolshevik revolution on Tuesday, the long-standing row over the body of its leader in the heart of Moscow has reignited. RT looks back on how Vladimir Lenin ended up as Red Square’s most controversial feature.

The debate over what should be done with the Bolshevik leader’s body never really goes away. However, there is usually a peak in April around Lenin’s birthday and another in the run-up for anniversary of 1917’s October Revolution, counter-intuitively marked on November 7th thanks to the change to the Gregorian calendar shortly thereafter.

2017 was no exception. This year, joining the usual chorus of voices calling for Lenin’s removal and burial was Chechen leader Ramzan Kadyrov, who said “we should stop staring at a corpse”. The call brought a predictable rebuke from the Russian Communist Party leader, Gennady Zyuganov, who claimed that President Vladimir Putin promised him that no such move would happen as long as he holds the office. His supporters rallied on Tuesday carrying banners that said: “Hands off the mausoleum!”

Proponents of burying Lenin usually argue that this would be in line with Orthodox Christian tradition and well as wishes of the man’s family. There is also the cost of maintaining the remains and the mausoleum building, which is covered in part by the national budget, and partially by donations through a non-profit fund. Some say placing Lenin under the ground is necessary to bury the Communist past of the nation. Others go so far as to call for its public disgrace as a symbolic punishment for the crimes committed by the Bolsheviks.

Defenders of the status quo cite Lenin’s role in creating a state based on a dream of unprecedented equality – a dream that, arguably, forced capitalist nations throughout the world to pass labor reforms and become less socially unfair. They also see nothing wrong with keeping the remains unburied, citing similar examples like that of Russian surgeon Nikolay Pirogov, whose embalmed body has been on display since the 1880s in the city of Vinnitsa in what is now Ukraine. Pirogov’s body is kept in a crypt under an Orthodox church, treated not unlike a saint’s relic by some churchgoers.

The Russian government over the years has tried to keep distance from the debate, saying that burying Lenin had little practical value and would likely hurt the feelings of many elderly people. It also appears to be trying to maintain its distance from the body itself. In recent years the mausoleum has been hidden from the public eye during the military parade for Victory Day – among the most important public events in Russia – in contrast with the way Communist leaders observed the march from atop the memorial building.

For the Russian public the issue seems to be gradually losing importance. Opinion is divided into roughly equal parts, between those who want Lenin’s body to stay indefinitely, those demanding relocation and those who suggest the burial should take place at some point in the future. The latter opinion has been gaining popularity over the years.

‘Living sculpture’

Vladimir Lenin died in January 1924 after two years of struggling with severe health problems and increasingly strict isolation imposed by fellow party members. Initially there was no intention among the Bolsheviks to keep his body preserved for more than the few days needed to lay in wake, but Lenin’s temporary mausoleum attracted flocks of people wishing to say goodbye and the stream showed no sign of abating.

As the saying goes, nothing is as permanent as a temporary solution. Several days were stretched into two months through an initial embalming procedure and thanks to unusually cold temperatures during winter. By the March thaw, the Communist leaders were discussing ways to keep the body in shape even longer, with different figures advocating their favorite methods. The suggested solutions included freezing the body solid, or storing it in a container full of formaldehyde or in a sealed capsule pumped full of nitrogen.

Even then, there was no goal of preserving the body indefinitely, as evidenced by the proposal of military commander Kliment Voroshilov, who said: “I propose doing nothing. If the body holds up for another year without change, this is already good enough.”

Crazy as it sounds, there were two coexisting government commissions at the time: one tasked with organizing the burial of Lenin and one with keeping his body intact and on display, and many people were members of both.

Eventually an experimental embalmment procedure was authorized and performed by Vladimir Vorobiev, a professor of medicine, and Boris Zbarsky, a biochemist. The procedure started a decade-long experiment which blended science, art and, arguably, mysticism in a constant process of “reembalming, rescupturing and substituting” the remains of Lenin with specially developed artificial materials, writes professor of anthropology at the University of California, Berkeley, Alexei Yurchak.

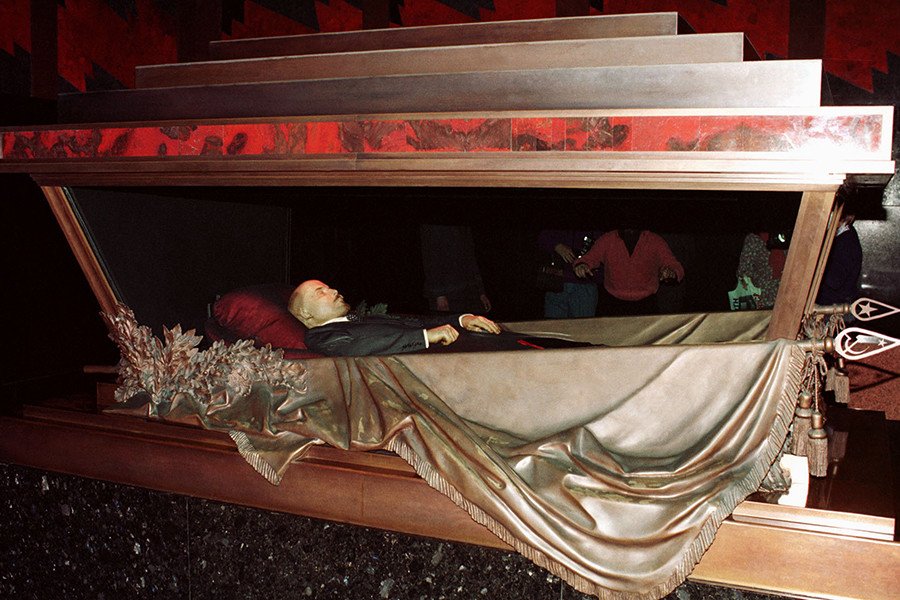

The care given to the remains of Lenin went far beyond simply preventing decomposition. A special research institute with dozens of specialists and lucrative funding was working hard on new ways of making the body look and feel as if it was freshly dead. They devised special fluids to keep the skin elastic and colored the right way; pumped small amounts of a paraffin-based substance under the skin to compensate for the inevitable loss of body fat to degradation; found ways to keep even the smaller joints flexible. One veteran scientist described the subject of his endeavors as a “living sculpture” to explain the work.

Interestingly, the majority of Soviet people could not appreciate the effort. While hundreds of thousands visited the mausoleum, all they could see was an immobile shape in a sealed container with only hands and face uncovered. The state of the rest of the body was witnessed only by the caretakers and inspectors, who described their findings in regular classified reports to the party leadership.

While usually the reports commended the scientists for making their charge better and better over the years, sometimes things went gravely wrong. In March 1945, for instance, after a skin-enhancing procedure a piece of epidermis from Lenin’s right foot went missing. Despite all efforts, it was never found and later replaced with a graft.

Source of sovereignty

There are plenty of historic precedents for people’s remains being preserved and put on display. In addition to the aforementioned Pirogov, there is the famous example of English philosopher Jeremy Bentham, whose figure can be seen at University College London – with the original head replaced with a wax cast, and displayed next to the body. Another example is Eva Peron, whose preserved body is a pilgrimage destination for devoted Argentinians – and fans of the musical. But the persistent embalmment of Lenin is a unique Communist tradition.

The extraordinary amount of resources poured into Lenin’s preservation may seem irrational, considering how little practical value the project had besides an occasional chance to show off the body’s flexible neck to foreign dignitaries. A waxwork statue would arguably serve as just as good a centerpiece for propaganda. Some argue that the entire program was conceived as a quasi-religious cult, with Lenin’s remains playing the role of a “Communist saint” relic to win the hearts of a deeply religious nation. Contemporary records disprove the theory, showing that Communist officials were concerned that such a comparison may arise, and took steps to avoid it.

In the Soviet Union the corps of works by Lenin was used as a source of legitimacy by the Communist party. Any serious policy had to be justified by a suitable quote, and finding the right one for the occasion was a necessary skill for any senior bureaucrat. Every head of the USSR from Stalin to Gorbachev had to observe this ritual, and Stalin’s attempt to add his name to that of Lenin’s failed spectacularly. The embalmment of the corpse was a continuation of the personality cult that, according to a popular saying, made Lenin “more alive than all the living”.

This newfound tradition went beyond the Soviet Union. People like “Mao Zedong and Ho Chi Min were legitimized… through their references to Lenin,” Yurchak told RT. “And all other communist and quasi-communist bodies that were preserved by the Mausoleum lab in Moscow, were preserved as references to Lenin’s body. Had his body not been preserved in the first place, the other ones would not be preserved either.”

Apart from Lenin, nine bodies underwent the same treatment, eight of them with help from Moscow. The body of Mao was embalmed in a similar manner, but independently from the Soviet scientists – to stress Beijing’s opposition to post-Stalin’s USSR, and their claim that China was the true heir to Lenin’s teachings, the anthropologist added.

The argument is supported by a famous hoax by avant-garde artist Sergey Kuryokhin. In early 1991, he gave an extensive interview for a television program, in which he stated that Lenin and other Bolshevik leaders were fond of mind-affecting mushrooms. Lenin consequently was transformed from a human into a human-shaped mushroom with the properties of a radio wave. The absurd claim was backed by pseudo-scientific babble and lots of visuals.

The program was intended as a satire on sensationalist TV reports and Communist ideology desperately trying to reform itself through the perestroika, but it also flipped the mythical iconography of Lenin upside down, still depicting him as more than an ordinary man, but in an utterly ridiculous way.

Slow path to insignificance

The turbulent 1990s transformation of Russia left little place for Lenin’s icon, despite its symbolism. The lab that performed renewal procedures was defunded, initially forcing dedicated employees to work for free. In 1993 a special fund was founded to collect donations and use them to continue the project.

The Lenin Mausoleum fund was the sole source of resources for a 12-strong lab working on Lenin’s remains, its longtime director Aleksey Abramov told RT. Only in 2013 was some public money allocated for the mausoleum. According to a budget acquisition disclosure, last year Russia’s Federal Protection Service – the organization tasked with the personal security of senior government officials and places, including the Kremlin – spent about $222,000 on the preservation effort. “Our government was receptive to the needs of the mausoleum lab,” he said.

The ultimate fate of the extraordinary exhibit remains undecided, but it appears that the current situation will be preserved along with Lenin’s body until a time when it becomes largely insignificant for the living.

By Alexandre Antonov, RT

@alantonov