Turkey & Greece re-open old wounds in borderline argument

The presidents of Turkey and Greece, Recep Tayyip Erdogan and Prokopis Pavlopoulos respectively, made sure that the former’s historic visit to Greece went beyond anodyne pleasantries. The matter at hand was interpretation of the 1923 Treaty of Lausanne.

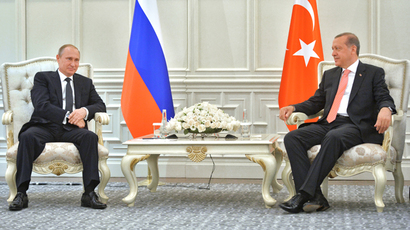

In his first visit as president, the first such visit by any Turkish president since 1952, Recep Tayyip Erdogan walked along the red carpet in Athens on Thursday, flanked by his Greek counterpart, Prokopis Pavlopoulos. If ever a host nation pulled out all the stops for a visitor, then Greece did so on this occasion: Athens ground to a halt as thousands of police and security personnel left nothing to chance.

Such an approach was in accordance with that adopted by Turkey since the attempted coup of 2016, which killed 250 people and left almost nine times that number injured. Followers of the exiled Turkish preacher Fethullah Gulen, who resides in the United States and whom Ankara blames for the coup, are dubbed the ‘Gulenist Terrorist Organisation’ (FETO) by Turkish authorities. Scores are arrested on a regular basis, and around a thousand Turks have sought political asylum in Greece on this basis, according to Turkish FM Mevlut Cavusoglu as cited by Anadolu Agency.

In response to extradition requests, Greece has said that they ought to be founded upon something more solid than mere circumstantial evidence, according to Hurriyet.

READ MORE: Erdogan urges Lausanne Treaty be revised

During the first in half a century visit, the Turkish president saw fit to speak of “outstanding issues” with the Treaty of Lausanne, whereby Turkey ceded territory which it had possessed under the Ottoman Empire. Greece being one of those territories, Pavlopoulos naturally described the treaty as “non-negotiable.”

Greek Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras could be expected to express discord with Erdogan’s position, and the genuinely baffling nature of Erdogan’s stance provided an easy route for Tsipras to follow.

“The truth, is I’m a little confused regarding if what he is putting on the table is to modernize, to update, to comply with the Lausanne Treaty,” the PM said, as cited by Reuters.

Erdogan has said in the past that he has no intention of redrawing Turkey’s borders, and uninhabited islands in the Aegean Sea have been enough to bring the nations close to war in recent years. The tension stems in part from the rights of access, attendant to control of the islands, to various minerals which lie below the sea. Erdogan also pointed out that Turkey has been a NATO member for a longer continuous period than Greece has, and that the Muslim minority in the country needs a guarantor.

Erdogan is no stranger to controversy, having to all intents and purposes re-shaped the office of Turkish president in his own image. Even before the failed coup, Erdogan had to contend with a restive Kurdish population in his country’s east, as well as balancing NATO membership and maintaining ties with Russia, Iran and the Gulf monarchies. Relations with Greece would be a Gordian knot for any Turkish leader.

There are deep historic roots for the pride of both nations, and those roots are intertwined. The Ottoman Empire was the main power in the Middle East for centuries, and at its peak under Suleiman the Magnificent was arguably the most powerful empire in the world. Ancient Greece is widely regarded as the cradle of philosophy, literature and democracy, and its marriage with Rome gave the world Byzantium and its capital of Constantinople. Over time, the Turks pushed westward, while European crusaders pushed eastward. The fourth crusade involved the sack of Constantinople – western Christians robbing and murdering eastern Christians. The historian Runciman stated flatly that “never was a greater crime committed.”

The subsequent Turkish conquest of Constantinople led to its renaming as Istanbul, and the Ottoman Empire expanded into Greece and the Balkans. The strength of the Russian Empire curbed Ottoman ambitions for a time, but the Great War dragged everyone in and led to the destruction of Smyrna – now Izmir – in 1922. This set the seal on Turkey’s reputation for the Greeks to this day.

By the Second World War, Greece was surrounded by Communist governments and seemed to be going down the same road. The West allegedly resorted to desperate measures to ensure that Greece’s ports and shipyards did not become available to Stalin. By contrast, and like other Mediterranean countries, Greece has experienced fascism, and in what proved to be one of its last acts, the Greek junta annexed the island of Cyprus in 1974. The Turks responded by invading the north of the island, which remains de facto partitioned to this day. While elsewhere in Europe Turkish membership in the EU is a bone of contention, the Cypriot question has been the usual flashpoint for Graeco-Turkish relations in recent years.

Erdogan’s visit, however, may herald a more direct approach. Such an approach may be a deliberate choice, as waves of migrants continue to use Turkey as a conduit to enter Greece and thus the EU, and the two countries are now linked by the Interconnector pipeline. Also, Turks continue to live in Greece, in Thrace, and Erdogan made sure to visit them on the second and final day of his visit on Friday.