Scientists record Earth’s ‘hum’ in depths of the Indian Ocean

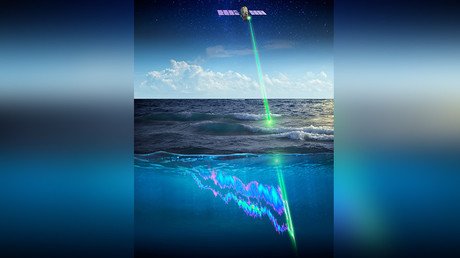

Scientists have for the first time been able to record the mysterious ‘hum’ generated by the Earth’s movement deep underwater, a phenomenon which could help us understand the inner workings of the planet.

There have been attempts to capture the low-frequency sound since 1959, although it wasn’t until 1998 that Japanese scientists finally managed to record it on land. The hum is caused by “free oscillations,” or the slight expanding and contracting of our planet.

Nobody knows exactly where these oscillations are coming from. One theory is that it’s the force of ocean waves pounding on the seabed. Another points to acoustic resonance – when the frequency of one vibrating object matches the natural frequency of another – causing the second object to also vibrate. Some scientists believe that atmospheric turbulence could be causing the hum sound.

A team of scientists led by Martha Deen, a geophysicist at the Paris Institute of Earth Physics, gathered 11 months worth of data from 57 seismometer stations on the seafloor of the Indian Ocean around La Réunion Island, east of Madagascar. The seismographs were first placed there to study volcanic activity.

“A low noise level is needed to observe the small signal amplitude of the hum,” Deen and her colleagues write in their paper published in Geophysical Research Letters.“At the ocean bottom, the noise level at long periods is generally much higher than at land stations.”

After muting the sounds of the ocean and electronic interference, they cross-referenced their recordings with those from a land-based station in Algeria. The scientists then discovered that the hum of the Earth’s oscillations peaks at frequencies of between 2.9 and 4.5 millihertz, which is around 10,000 times below what the human ear can possibly hear, which is 20 hertz. The team’s success at recording these low-frequency noises may also have other, more interesting applications.

“The Earth’s hum can be used to study the Earth’s deep interior,” the paper reads. While scientists usually study the inner levels of the planet using seismic waves generated by earthquakes, data from the hum sound could help map out the Earth’s interior, since the noise is constant, while earthquakes only erupt periodically.

What exactly lies behind the oscillations, however, remains a mystery. The study’s findings seem to suggest that atmospheric turbulence can only account for part of the vibrations, which leaves our planet with an eerie, low-pitch echo.