Australian Army chief talks up threats to ‘ethical’ warfare – but track record suggests hypocrisy

The chief of the Australian Army has discussed the laws of ‘ethical conduct’ on the battlefield in an age when AI is set to transform conflict, but questions abound as to whether Canberra is on shaky moral ground itself.

Australian Lieutenant-General Angus Campbell addressed the question of drones and robots on the battlefield, and more specifically those countries and groups that lack the “ethical foundations upon which we seek to build and employ our military capability."

"We... will always be asking the question, 'What is the right ethical construct, and ultimately behavior and actions?' Others will not… That is absolutely a threat to any nation-state that believes in the laws of war and in ethical conduct," he told reporters from Fairfax Media on the weekend.

By way of example, Campbell mentioned Islamic State’s (IS, formerly ISIS) use of simple commercial drones against Iraqi government forces – a tactic that has reportedly had very limited success on the battlefield.

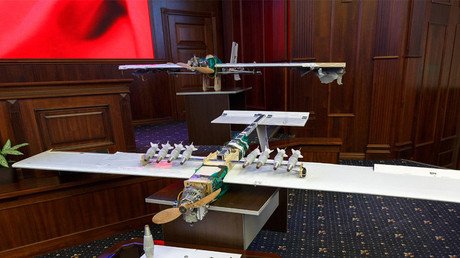

However, the army chief failed to mention the more recent example of such crude battlefield tactics which was put on display in Syria. On the evening of January 6, Russia’s Khmeimim Airbase was attacked by 10 unmanned aerial vehicles, while another three targeted the Russian maritime logistics base in the city of Tartus. Seven of the UAVs were brought down by the Pantsir-S air-defense system. Russia proved its expertise in electronic warfare as it managed to hijack six of the aircraft – three were crashed into the ground, while the other three were landed without incident.

Russian experts said that the know-how behind the drones was only obtainable “from a country possessing state-of-the-art technologies, including satellite navigation and remote control of… explosive devices [for] release at certain coordinates.”

In other words, IS militants lack the technological expertise to pull off such a sophisticated attack on their own.

READ MORE: Threat of terrorist drone attacks is real, says Russian military after assault on base in Syria

Other questions remain concerning Campbell’s implicit assertion that Australian fighting forces somehow have an advantage over other countries when it comes to “ethical conduct.”

Some would query the comments, considering Australia’s history of participating alongside the United States in the pursuit of regime change.

Presently in Syria, for example, Australia is one of the countries in the US-led coalition against IS forces. From the beginning of the military operation, however, the “ethics” behind the campaign have been called into question. That is because this group of countries never received the formal consent of the Syrian government to launch a military operation on its territory.

Yet there is a far more serious reason for questioning Campbell’s belief that Australia is somehow predisposed to ethical behavior – namely its direct participation in the US drone program.

Since the late 1960s, Australia has played host to the ‘Joint Defense Facility Pine Gap,’ which serves as a key hub for US intelligence gathering. Over the years, and especially around the time of the first Gulf War, Pine Gap saw its cooperation with the US become increasingly military in nature.

On February 4, 2002, the CIA first used an unmanned Predator drone in a targeted killing, in Afghanistan. Hundreds more would follow, and, according to files acquired by Edward Snowden, Pine Gap played no small role in these extrajudicial killings.

The files showed that Pine Gap collects the geolocation of mobile phones from the Pacific Ocean to the edge of Africa. The site is powerful enough to provide a person’s location in real time – invaluable information for conducting drone strikes.

According to the Bureau of Investigative Journalism, US drones were responsible for 7,200–10,500 deaths, with between 700 and 1,500 civilians and 240-330 children murdered.

Some human rights advocates say the killings not only warrant an investigation, but could make Australia complicit in actual war crimes.

In an interview with Background Briefing, Emily Howe from the Human Rights Law Centre said there may have been “violations of the law on armed conflict, or war crimes as it is called colloquially…unlawful killing using drones is not only a violation of international law, it’s a violation of Australian [law] as well.” Howe adds: “War crimes are a crime under the Australian criminal code…”