Stalingrad at 75: Five ways iconic battle turned tide of WW2

February 2 marks the 75th anniversary of the German surrender at Stalingrad. While the five-month battle remains a symbol of World War II, its practical importance to defeating the Nazis deserves more attention.

1. Inflicted huge losses

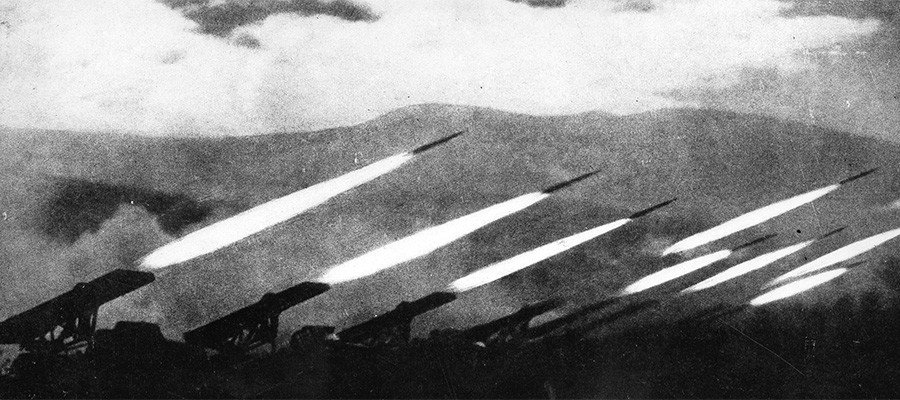

Stalingrad was the biggest and bloodiest battle in the history of warfare. Estimates vary, but fighting between August 1942 and February 1943 is thought to have resulted in up to 2 million casualties, with more than a million dead.

This was not just a reflection of the forces involved, but the specific circumstances. Adolf Hitler’s increasingly obsessive desire to capture the city as he lost more and more troops came up against the resilience of the Soviets, who were defending their homeland under Joseph Stalin’s newly-issued Order 227 (“Not one step back!”).

The battleground was the bombed-out hulk of the city, providing the stage for the most notorious and vicious street fight in history – still known as the “Rat War” by the Germans – in which there was equal threat from being picked off by a sniper, ambushed crossing the road, or bayonetted in a sewer at night. The latter was a tactic favored by the Russians, who wanted to ensure the advancing army was constantly sleep-deprived and anxious.

This was a war of attrition that Germany could afford far less than the Soviet Union.

“For the Germans it becomes a meat grinder. Every division they send in is weakened, so they have to pull new ones off the flanks. According to 6th Army’s loss figures, most divisions go in rated combat-ready. Within a week, they’re rated either as weak or exhausted. The attrition rate is phenomenal. The Luftwaffe’s rubbling of the city only exacerbates things. In early November, they run out of divisions,” is how American historian David Glantz described the course of the battle.

Soldiers of the elite German 6th Army were not designated to be exchanged one-for-one with newly-trained peasant conscripts, nor were Panzers built to be stuck for months in static positions, to be shot from second-floor machine gun nests which they couldn’t even lift their guns to target. The idea of constant, aggressive engagement, disregarding large losses, was ingrained in Russia’s historic military doctrine. It found its ultimate application in World War II, where the Soviets possessed a significant advantage in manpower – and at Stalingrad, Hitler danced to their tune.

2. Handed Germans their first major defeat

Stalingrad was attacked as part of Operation Blau, which thought to cleave Soviet forces and allow Germany access to valuable oil in the Caucasus. But as it developed, the battle quickly grew its own logic and much bigger stakes, which fell outside any operational implications.

When Marshal Georgy Zhukov successfully conducted his pincer movement to encircle the weakened German forces, this represented the largest and most clear-cut defeat inflicted on the Wehrmacht since the start of the war. In comparison, the justly celebrated contemporaneous Allied victory at El Alamein involved forces and casualties that were at least ten times smaller.

“At Moscow in 1941, the Germans were repelled, here they were destroyed. Before, they could say this was a temporary reversal, but here Hitler ordered for the 6th Army to be rebuilt from the ground up – this was not a defeat that could be concealed,” says Konstantin Zalesskiy, a prominent historian.

After the devastating losses just 18 months earlier, the Red Army was able to claim superiority over the vaunted invaders – both a function of improved doctrine and tactics, and a platform for future gains, as well as a remarkable triumph in its own right.

3. Gave hope to the world

Involuntarily, those who refer to Stalingrad as “symbolic” in the present day are speaking more in abstract and iconographic terms. But for those who lived through World War II and lived in fear of invasion or death, the importance of the battle to morale was far more immediate.

“There was a sense that if the city fell, all would be lost,”says historian Jochen Hellbeck, explaining that in Britain even at the time, the magnitude of the battle was clear to every radio bulletin listener.

Considering Germany’s dwindling resources, the destruction of the aura of invincibility that had surrounded its forces immediately cast the entire fate of World War II in a different light.

Conversely Stalingrad was a “shock to the German population,” says Zalesskiy.

For many residents this was the first realization that what had hitherto had been a triumphant foreign adventure could end up on their doorstep, and that every act of barbarity would meet its own retribution, as indeed came to pass.

In turn, German propaganda soon became more doom-laden, and just a fortnight later Joseph Goebbels made his apocalyptic Sportpalast speech, insisting that the very survival of his people was in the balance, and asking his audience, “Do you want a war more total and radical than anything that we can even yet imagine?"

4. Sent Hitler over the edge

“The problem was that Hitler had invested so much in propaganda terms – even Goebbels was worried about how much was being invested – into the capture of Stalingrad, that it was a question of pride, of vanity,”says Anthony Beevor, the best-selling war historian.

But the issue goes deeper. Hitler’s rapid ascent, both political and military, relied on manic self-belief and optimism that was carried straight into Operation Barbarossa in 1941. Even before Stalingrad, after the Soviet Union refused to surrender in the planned two months, the Führer was – perhaps subconsciously – aware that for the first time the endgame did not look promising.

A victim of the sunk cost fallacy, instead of cutting his losses and suing for peace, he doubled down, looking for the big win. And once the battle started, he did it again and again, even when there could no longer be any military justification for taking the city.

The realization of defeat, the impact of which he freely admitted, devastated Hitler. Out went the natural ebullience and Wagner sessions with the high command, in came regular amphetamine injections and a depression that prevented him even from making key addresses to the nation.

READ MORE: Hitler was heavy drug abuser, German soldiers pill-poppers, book claims

This is how two of his personal aides Otto Guensche and Heinze Linge described his mental state in the period to the Soviets who captured and interviewed them.

“The attacks of nervous irritation increased. One moment Hitler’s collar was too tight and was stopping his circulation; the next his trousers were too long. He complained that his skin itched. He suspected poison everywhere, in the lavatory cistern, on the soap, in the shaving cream or in the toothpaste, and demanded that these be minutely analyzed. The water used for cooking his food had to be investigated as well. Hitler chewed his fingernails and scratched his ears and neck until they bled. Because he suffered from insomnia, he took every possible sleeping pill,” reads the document, known as The Hitler Book.

In the next two years he would retreat further into delusion and despondency and literally into his underground bunker.

5. Set timer for the German defeat

Some historians like to argue that it was December 1941 – when Hitler was stopped on the edges on Moscow, and the United States entered the war following Pearl Harbor – that decided the outcome of World War II.

READ MORE: 1,418 days of WWII viewed through lens of legendary Soviet photographer (GRAPHIC IMAGES)

But if that month – better understood now, in hindsight – loaded the gun, Stalingrad firedit. Thanks to each factor above, it literally changed the direction of the war.

The Nazis never made any further advances into Russia. In fact, having scarcely lost before, other than the Third Battle of Kharkov in March 1943 they barely won another battle on the Eastern Front, and did not conduct a single successful campaign anywhere.

The victory at Stalingrad did not just save millions of Russians from Hitler’s occupation, but millions abroad, likely shortening the war by months or years.

Igor Ogorodnev for RT