A chance discovery by a team of archeologists in Turkey may have revealed one of the most significant sites in the history of Christianity after years of fruitless searching. And they’re now planning an underwater museum.

When Constantine I, the first Roman Emperor to convert to Christianity, chaired the ecumenical Council of Nicaea in 325 AD, bishops from across the world descended on Lake Ascanius to iron out divisions in the early Christian church. The modern-day lake, Lake Iznik in Turkey, has for years been the focus of archeologists trying to find treasures from that ancient time.

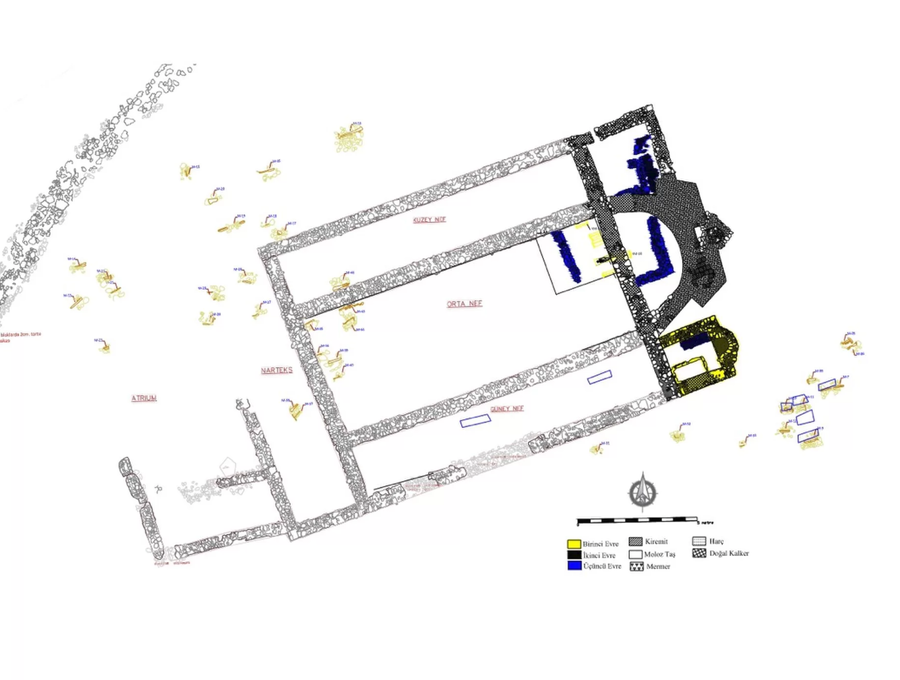

Now it turns out, what they had been searching for was right in front of them the whole time. And they finally found it thanks to some new aerial photographs commissioned by the government of Bursa province. The snaps clearly revealed the structure of a church submerged underwater.

Turkish archeologist Mustafa Şahin, who is the head of archaeology at Bursa Uludağ University, has been undertaking field surveys of the lake since 2006, but had never discovered the church. The ironic thing was, according to Şahin, the Bursa City Hall photography team had been capturing aerial photographs of the lake since 2013, “but hadn’t thought of contacting any expert.”

“So when they started capturing aerial pictures of the lake again, team member Saffet Yilmaz contacted me and asked if the remains of the structure might have meant something,” he said, adding that it was a shock to see the structure of a church so clearly in the images.

Şahin believes the location of the church ruins could mark the site where the First Council of Nicaea was held nearly 1700 years ago. He also believes it marks the spot where Saint Neophytos was martyred in 303 AD — and that the church could have been built to honor him.

Archeologists say there is also evidence that an earlier temple dedicated to the Greek and Roman god Apollo could have been located underneath.

An earthquake in 740 AD destroyed the church and caused it to sink below the lake — about two or three meters below the surface and 50 meters from the shore.

“The hardest part of the underwater excavation is that visibility sometimes drops under 10cm because of intense algae and plankton activity,” Şahin said. Waves hitting archeologists as they try to work is another problem, so they take the soil from the site and sift through it on the shore instead.

Şahin has big plans for the site and said he would like it to become Turkey’s first underwater museum, which would incorporate a 20-metre tower to allow tourists to see the ruins from the shore, a walkway directly over the lake itself and a glass room submerged under the water where visitors could pray at the site. There could also be a diving team, which would allow people to see the ancient structure up close.

The archeologist said there is “no need to wait” until the excavation is over to build the museum and that it could open as early as 2019. “With our excavation methodology, the visitors aren’t a distraction for the work in progress,” he said.

Think your friends would be interested? Share this story!