Thursday's aborted launch of the Russian Soyuz spaceship may have sent the International Space Station's work into disarray, but it also highlighted how much effort Soviet space engineers put into their creations.

The apparent failure during booster separation of the Soyuz-FG launch vehicle rocket became the third time in history where crew lives were saved by a system called SAS, a Russian abbreviation for "system of emergency rescue." It's the Russian answer to the problem of how to save people during a manned rocket launch if something goes wrong.

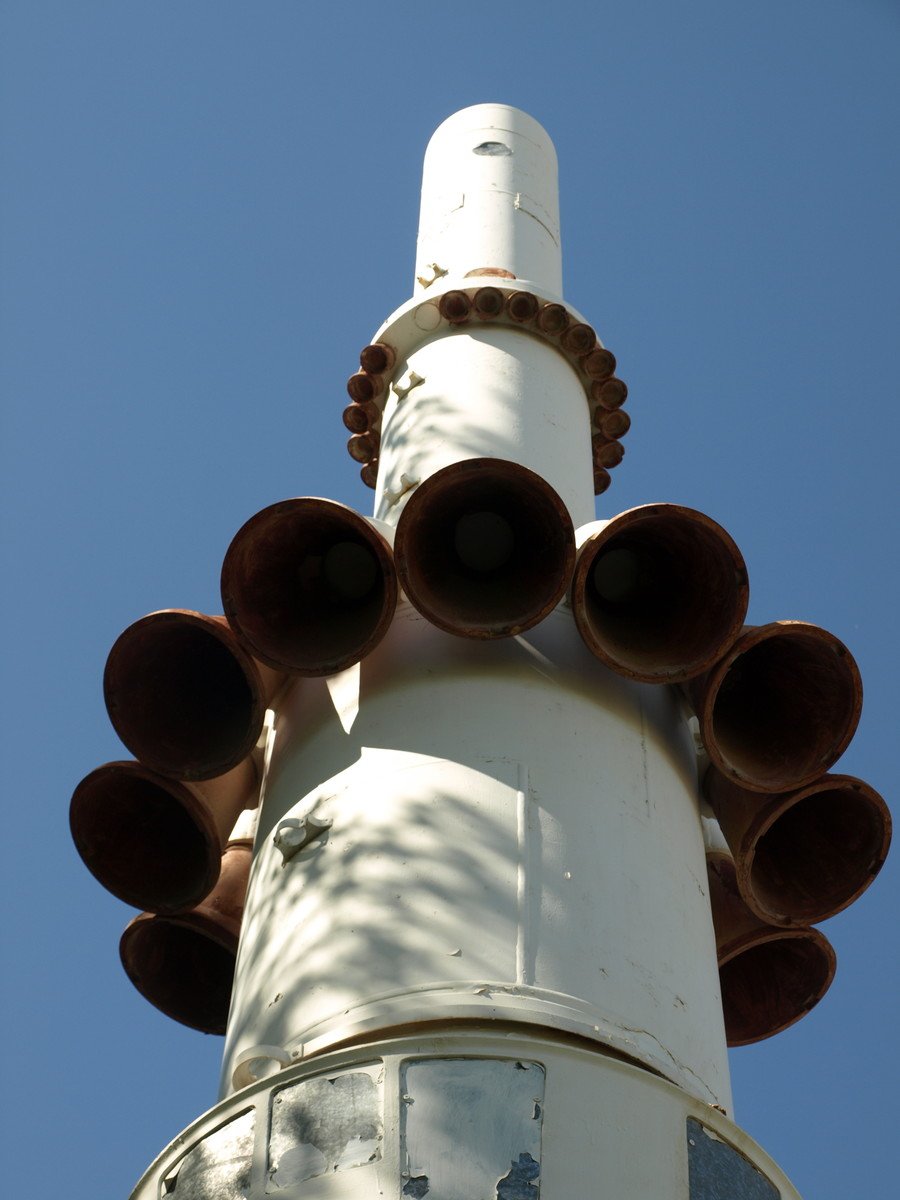

In its entirety the SAS is basically a small solid-propellant rocket mounted above the payload fairing. If there is a need to abort the launch, the Soyuz spacecraft under the fairing sheds the lowest of its three modules while the fairing separates into upper and lower sections. Then the entire stack is towed up and away from the dangerous rocket by the SAS main thrusters, while four grid fins at the bottom make sure that the mini-rocket stays on a stable course. At a safe distance the space capsule separates from the frontal module and the fairing, and drops down to break speed and parachute to the ground.

Mounting the SAS atop the rocket is one of the more dangerous parts of the assembly process, because of its highly explosive propellant. During a launch the system is turned on about 15 minutes before liftoff. It can engage itself under some conditions, like if the rocket starts to tilt on one side, or can be engaged manually. Two operators on the ground must each press two buttons simultaneously to fire off the SAS – a measure meant to prevent false triggering.

Ironically, the first major incident when SAS was used resulted in a death. In December 1966, a Soyuz 7K-OK, a then experimental spaceship for manned missions, was supposed to be launched with a mannequin on board. The launch was aborted after one of the four first-stage boosters failed during the ignition phase.

About half an hour later, as ground crew were preparing to take it down for analysis, the SAS activated and rescued the soulless passenger as intended. The system was triggered by rotation of earth, which its automation interpreted as a rocket deviating from course. The exhaust from SAS thrusters started a fire and caused the launch vehicle explosion, which killed one of the officers on the ground.

In three subsequent years the system saved three payloads during failed launches of the Soviet lunar program. In July 1969 came, arguably, its most spectacular equipment rescue when the system was tested as part of the second launch of the ill-fated soviet five-stage megarocket N-1. The behemoth launch vehicle managed to climb 200 meters before its 30 first stage engines were ordered to shut down. One didn't, and the rocket started to tilt, resulting in activation of the SAS. While on the ground the biggest explosion in the history of rocket failures unfolded, the launch escape system succeeded in saving the payload – a prototype of lunar orbiters and a mock-up of a lunar lander.

The first time the SAS was called to actually do its job was in April 1975, except by the time it was needed, the rescue tower was no longer on the rocket. During the launch of Soyuz 18a spacecraft the malfunction was detected after the separation of the second stage and well after the payload fairing along with the SAS main and backup thrusters were jettisoned. The escape protocol for this situation is to use the Soyuz spacecraft's own engines to get away from the rocket, detach the two modules not needed for descent and hold fast. However, the accelerations experienced by Vasily Lazarev and Oleg Makarov on that day exceeded a wobbling 20G.

The capsule landed in the middle of nowhere, and bruised cosmonauts had to wait for rescue in the sub-zero environment of a snowy mountain in western Kazakhstan. The crew could not be certain that they hadn't overshot into Chinese territory, so one of the first things they did on the ground was to destroy classified documents about the Soviet space program. The first people to find them were local surveyors, and one of them managed to rappel down from a helicopter to the landing site to help the cosmonauts. The dedicated search and rescue team only managed to pick them up the next morning, when the weather became more favorable. Makarov reportedly had to threaten the pilot of the rescue helicopter to stay on the mountain unless he allowed the civilian surveyor to get on board in defiance of regulations.

The biggest achievement of the SAS before this week was saving the lives of the crew of the Soyuz T-10-1 ship in September 1983. Less than a minute before scheduled ignition a fire started on the rocket, quickly spreading up towards the payload. The escape system was launched from the ground and blasted off the dying rocket, carrying Vladimir Titov and Aleksandr Serebrov to an altitude of about 1 kilometer. Titov later said he felt "like a puppy being pulled out of a river by a strong hand" at the moment.

The capsule landed five minutes later and were picked up by rescuers in a quarter of an hour. But the failure of the mission meant that the crew of the Soyuz-T-9 could not return home from the Salyut-9 space station as scheduled. Some Western media falsely claimed that Vladimir Lyakhov and Aleksandr Aleksandrov got stranded in space with no chance of return.

Both Titov and Serebrov did go into space after their brush with disaster multiple times. As did the capsule in which they escaped the 50-meter pyre – it was recovered and refurbished for the Soyuz T-15 mission in 1980.

What happened on Thursday was a third variant somewhere in between the 1975 and the 1983 incidents. By the time the Soyuz-MS-10 launch was aborted, its rocket already jettisoned the escape tower, but the fairing was still in place. So the capsule was pulled away by the backup thrusters mounted on the fairing. The crew members, Aleksey Ovchinin and NASA's Nick Hague, actually got away easy, having experienced a little spit to stabilize the capsule during descent and acceleration of just about 6g, which is less than every candidate for a space mission has to endure during training and regular medical tests.

The cause of the launch failure is yet to be determined, although apparently one of the boosters bumped into the second stage during separation. But the SAS once again proved it can be relied upon.

Think your friends would be interested? Share this story!