Vodka-fueled stabbing at Russian Antarctic station: Here’s what psychologists think happened

Working in the Antarctic can be bad enough without someone spoiling your book endings and insulting you over vodka. One Russian explorer stabbed another at a remote polar outpost, and media is abuzz with rumors and opinions.

Antarctic cold, months-long shifts, a small group of people and liters of vodka – with conditions like that, one wonders why a knife attack hadn't happened at the Bellingshausen research station before. We spoke to mental health professionals to find out what could lead to the bloody brawl and what could have been done to prevent it.

Antarctic attack

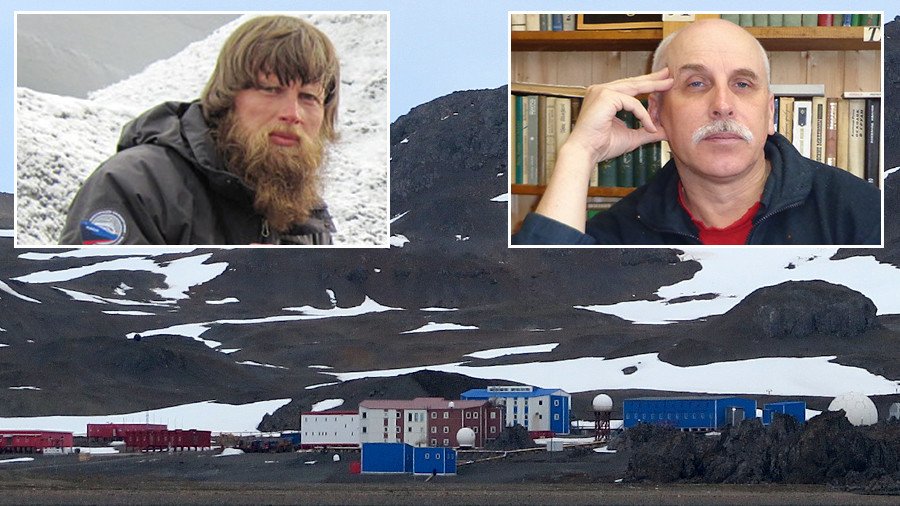

In early October, two co-workers at the Bellingshausen station, a Russian research outpost in the Antarctic, got into a fight. It ended with 54-year-old electrician Sergey Savitsky stabbing welder Oleg Beloguzov, 52, in the chest. Beloguzov survived and was urgently taken to Chile for treatment. The remorseful Savitsky surrendered without a fight and was sent back to St. Petersburg to await trial for attempted manslaughter, where he was placed under house arrest.

This is the first time ever an incident of its kind has happened at a Soviet or Russian Antarctic research station, says deputy director of the Arctic and Antarctic Research Institute, which governs Bellingshausen. He refused to talk about possible reasons, only saying the two had shown no animosity before and barely ever encountered each other during work.

Any confirmed details are hard to come by. What most reports agree on, though, is that both men were habitually drinking – alcohol is legal and said to be abundant at the station. The victim and the perpetrator had worked several shifts at the Bellingshausen before, including one of them together.

The exact motive is the most speculated-on part. One version goes that Beloguzov mocked Savistsky by offering to pay him to dance on the table. Another rumor making rounds online is that Beloguzov kept spoiling the endings of books Savitsky was reading.

Vodka on ice

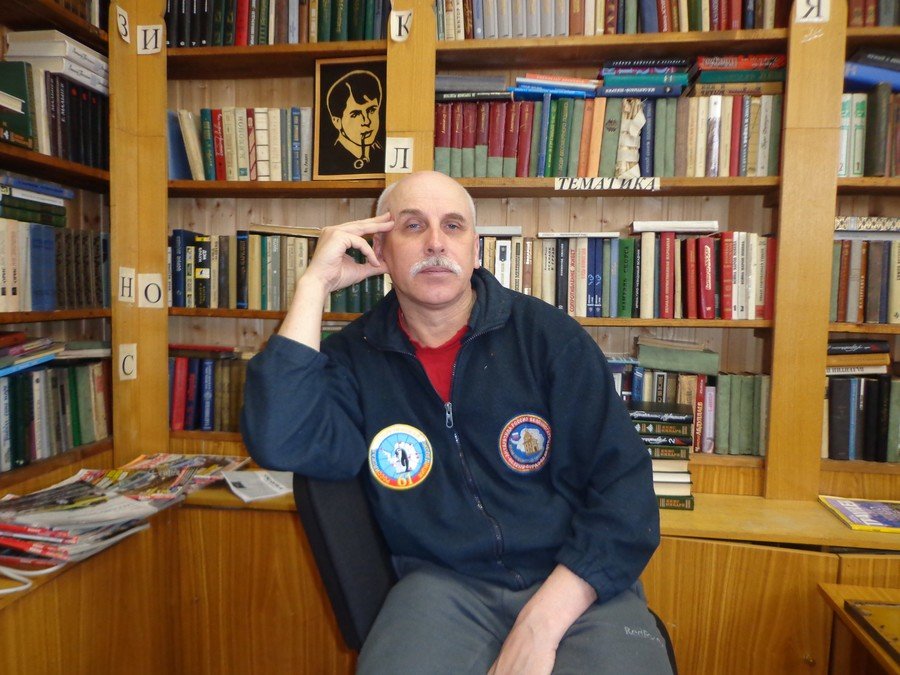

While most accounts agree that booze was involved in the altercation, alcohol at a polar station isn't necessarily a bad idea, says psychiatrist and addiction specialist Sergey Nurislamov.

For polar explorers to abstain is nonsense.

You need alcohol for warmth, if nothing else, Nurislamov believes. That said, safeguards should be in place to prevent addiction and resulting physical impairment. It can be as simple as using breathalyzers and Skype.

“You don't even have to send an addiction therapist to the South Pole. It's enough if they set up the equipment and ask the station's crew to use a breathalyzer on camera.”

Psychologist, therapist, and sociologist Lyudmila Polyanova begs to differ.

Alcohol is never a good idea.

Booze diminishes your self-control – and multiplied by pre-existing tensions and harsh conditions, “qualities resurface that could be unexpected for the person themselves.” Then, it's a stabbing waiting to happen.

It could be book spoilers – or anything else

Even if, as the most popular rumor claims, Savitsky really stabbed Beloguzov over spoiled book endings, it was likely just the straw that broke the camel's back in an already simmering situation.

If they had a conflict, anything could be the trigger. It could be silent treatment, it could be spoilers, or it one could be taking the other's favorite cup.

It's all a matter of conflict and provocation, Polyanova says.

Hidden tension

The two had been to Bellingshausen together before, and no-one appears to have noticed any tension between them – and it's likely they didn't see it coming either, Polyanova believes.

“There can be internal conflicts that accumulate, not understood by even the participants themselves – it's an unconscious process.”

It's not unlike marriage, Nurislamov says.

“Sometimes tension wells up. With married couples, nobody notices it either, they live together for 20 years and then a household fight can lead to murder.”

A therapist could help – or become a victim

Throughout the years, there hasn't been a practice of sending a therapist along with Antarctic exploration crews. Had there been one at the Bellingshausen, they could help – or get stabbed themselves.

“A psychologist in an isolated environment is a human like anyone else,” Polyanova says. “He is interacting with the rest of the group. He can have his own conflicts. This calls for a systemic approach… if we're talking about psychological help, this psychologist must receive it as well.”

Since the Soviet days of polar exploration, the state's approach has changed, and the work of Antarctic researchers is now seen as routine, Nurislamov says. But the conditions are still exceptional, and still call for teams of specialists to oversee the remote, isolated crews.

“There doesn't have to be a dozen professionals sitting there at the station. With modern communications, the specialists can remain hundreds or thousands of kilometers away.”

If you like this story, share it with a friend!