‘We wanted to be Red Army soldiers’: Polish veterans recall childhood memories of Warsaw’s liberation

It is often said that truth is the first casualty of war – and, indeed, when the bombs have stopped falling, the blood has been shed and the troops have stood down, another kind of war begins: A war of memories.

This is perhaps no more apparent than in the case of the experiences of Poland, and Eastern Europe at-large, after the defeat of Nazi Germany during World War II, and the decisive role played by the Soviet Red Army.

Friday marks the 75th anniversary of the liberation of Warsaw from the grip of fascism. A momentous date in history, it is still fraught with controversy – and regularly used as a political football so many decades later.

Whether it’s bickering over war-time monuments (treasured by some and hated by others), or a flippant comment uttered by a politician, these old wounds can still trigger international diplomatic squabbles. In Poland itself, vastly diverging narratives emerge about these historical events, depending on who is recalling them.

This wrangling over history has stepped up in recent years as Europe witnesses a worrying resurgence in Nazi-era ideology. From Warsaw to Kiev, far-right ideologues take to the streets in annual independence-day marches – their actions tacitly approved by nationalist governments encouraging patriotism often through revisionist history.

RT spoke to three Polish veterans, all of whom were children on the day Warsaw was liberated, who shared their firsthand experiences – snapshots of history through the lenses of those who really lived it.

‘Stop the blame game’

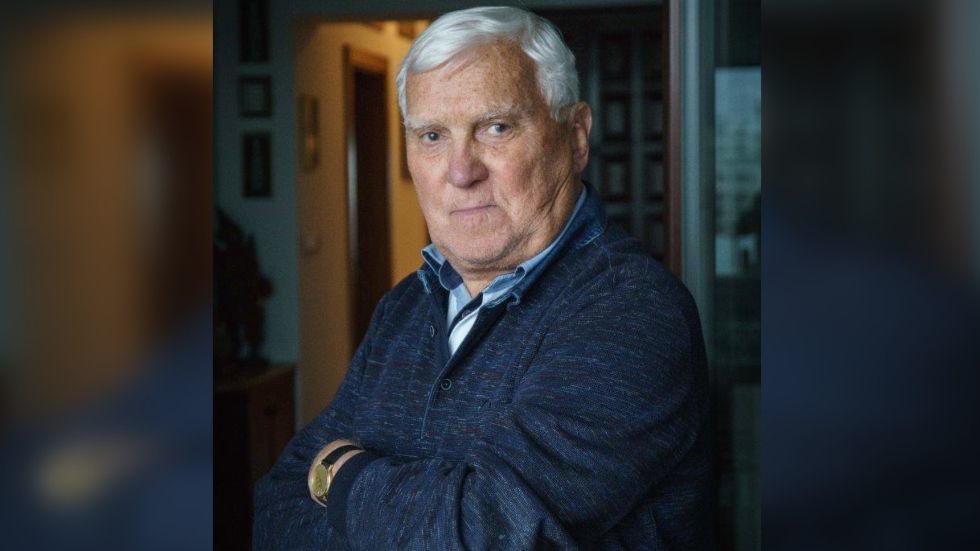

Jan Rybak was 15-years-old when Polish and Soviet forces wrested control of Warsaw’s Praga District from the Nazis. The Saska Kępa neighborhood, where he lived, housed the 1st Infantry Division of the Polish Army, while the Soviet soldiers remained on the outskirts of the city.

“It was extremely hard to get any basic foodstuffs in Warsaw, so I had to make regular trips to Lyublin, and I got all my rides from the Soviet military,” Rybak recalls. “The soldiers who gave me a lift shared their food with me. They gave me canned stewed meat and rye bread.”

Though he didn’t know it at the time, Rybak later learned the Red Army was approaching German forces from both north and south. Fearing encirclement by the Soviets, Hitler’s forces began retreating from Warsaw – and what was left of them was crushed on January 17 by the Poles.

Days later, Rybak remembers, there was a parade of Polish and Soviet troops near the Polonia Palace Hotel. The fact that it was still standing was “miraculous,” he says.

The parade was inspected from makeshift stands mounted on cargo trucks adorned with Polish flags. Teenager Rybak crossed the frozen Vistula river to watch – but he was one of “very few spectators” since the Germans had forced so many to flee and had levelled 90 percent of the city. There was not long to savor the moment of victory. “Right after the parade, the soldiers left for the frontlines.”

Rybak worries about the new wave of neo-Nazism rising in Poland – and the openness of today’s media unfortunately “provides a platform for people with extremist views” to rewrite history.

A lot of blood of Soviet and Polish soldiers was shed on Polish soil. We must be grateful to them for their heroic sacrifice, and respect and honor their memory.

He believes Poles who refer to the Red Army as “invaders” and “occupants” are trying to ingratiate themselves with the establishment. If relations with Russia are to be improved today, we “must stop all this finger-pointing and end the blame-game.”

‘They exclude the Soviet contribution’

Andrzej Kotnosvki was seven years-old in 1945, but still recalls his parents anxiously waiting for news from the Eastern Front. Red Army victories at Stalingrad and Kursk came as welcome news.

“As children, we were reenacting those battles in our games, and nobody wanted to play Germans. We all wanted to be Red Army soldiers,” Kotnosvki says.

These days, he balks at Polish authorities’ moves to distance themselves from celebrating WWII victories and efforts to strip the Soviet Union of credit for its role in defeating Nazi Germany.

It’s hard to imagine, he says, how the Red Army could have immediately withdrawn its troops from Poland and East Germany “leaving hundreds of thousands of their deceased” as the Cold War was just beginning.

It is with sadness now that I recall how we used to sing The Red Poppies on Monte Cassino and Oka at school in the 1950s, when absolutely no one living in post-war Poland had any issues with it.

‘We were barely alive’

Czesław Lewandowski experienced the final days of German occupation in one of the most harrowing ways of all. A camp prisoner at 11-years-old, he was freed while on a death march in mid-March.

“The marchers knew nothing about what was going on, because we were all just trying to survive,” he recalled. “No one thought about asking for any information. We were all barely alive.”

The column Lewandowski marched in was made up of around 1,200 prisoners. Those who weakened along the way were shot on Nazi orders. Eventually, those who had survived –only about 200– were liberated by Soviet tank crews near Lębork.

“All I knew was that I saw Russian soldiers, and I don’t recall what happened next,” he said. “I came to my senses in a room they had taken me to, waiting for my turn to be seen by a nurse.”

After that, Lewandowski spent two months at a hospital where he heard the news that Warsaw had been liberated. Later, he was on his way to Warsaw when the war ended.

“People around were shouting “Vivat!” and I didn’t know why. That’s how I learned the news” he said. Polish and Russian soldiers fired their guns and people were “overwhelmed with joy” because the victory meant they could finally “go on living.”

Think your friends would be interested? Share this story!